Translating yourself

AI translation tools open up exciting possibilities for certain books.

Translators, we probably all know, are the super-ninjas of the publishing world. They do huge amounts of nuanced work, often out of the limelight, to ensure an author’s intent in one language is faithfully reflected in another. It is not just a matter of words, either – human translation involves cultural empathy, semantic finesse and real commitment to understanding the thoughts and feelings of a work. Without them, literature would lose the empaths and crafters so essential to making a piece of writing be available in equivalent quality and fidelity in each language.

At a recent book fair, I was asked by a publisher if they could have the rights to my book in Arabic. Making my book on how publishing can embrace AI available in another 22 countries sounded great. My publisher, Richard Charkin of Mensch Publishing, made the deal.

Next, the challenge: the translation. In so many cases, a book has a finite audience (mine is generally in the publishing industry and a little more widely with people interested in AI) and the economics of book sales can prohibit a human translator doing the job. Many great pieces of work lie hidden from people who don’t speak the original language of the book, simply because that language is unknown to them. My new Arabic-language publisher, Al Arabi, suggested we should experiment with translation by AI.

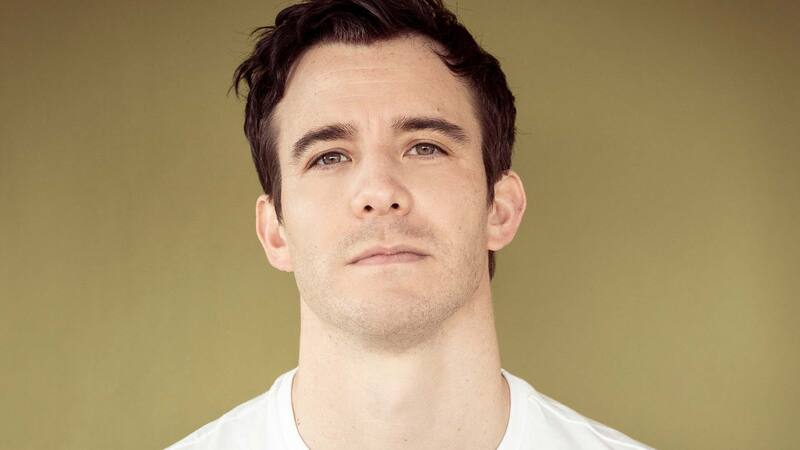

So I gave myself the task of "being the translator". It’s an odd one because (apart from not being a trained and experienced translator) though I’m called Nadim Sadek – an Egyptian name, meaning most people would reasonably expect me to be fluent in Arabic – I’m not. I speak only rudimentary Arabic and can’t read or write it at all. In short, I don’t have the personal capacity to translate from English to Arabic.

Yet I took on the responsibility, boldly saying I would deliver the manuscript. My intention was to employ AI to do the job for me. I decided to seek no-one else’s help, and instead, as an author, just find my way. I wanted to see how feasible this was, given that employing a translator would never be commercially viable.

First, I searched for "free, online, AI book translation tools’". I clicked on and attempted to work with a handful of them. I found most of them hard to use. They required me to have an expert knowledge of printing, which I don’t. Or to make decisive choices between one phrase or another – in a script/font/language I can’t read. Or they would suddenly present me with a payment option of thousands of US dollars to complete the task.

For a business book like mine, where conceptual communication rather than beautiful writing is the priority […] AI truly is an allied intelligence

Second, I resolved to try to use Large Language Models. I use several every day. Recently, I’d been experimenting with JAIS, an Emirati LLM, and felt its Arabic-sensitivity and training might make it the most suitable. This was a much more fruitful approach. JAIS and ChatGPT both have several models you can easily access, often for free. After a little experimentation, I chose the most powerful from both of them – the 70B parameter one from JAIS, and the o1 version from ChatGPT. These seemed to produce the most sophisticated language outputs that my small team of testers deemed best. They had also read my book in English and reported that the translations were surprisingly good – not sophisticated nor beautiful, but true to my work and suitably conveying my meaning. I pressed on.

Generally, the models don’t like to be given a whole manuscript. It is difficult for them to resist paraphrasing, summarising and distilling, even if you instruct them well. It was important to instruct them accurately, such as: "Please translate this in standard Arabic that will be read by professionals in the publishing industry. Ensure it is business-like but accessible. Don’t summarise, paraphrase or distil. Use the same tone of voice from one section to the next. Remember these instructions for each new passage I upload for you." With some experimentation around these sorts of instructions, the translated text began to emerge in a form that everyone thought was acceptable, even good.

There were other problems to overcome. JAIS would frequently halt the translation and say that it would not deal with forbidden concepts. I had no idea which section of a passage might have offended it or why, and it didn’t help me to know. So, though I wanted its Arabic language expertise, it didn’t help me to work with it further. ChatGPT had no such qualms about any of my work, and dutifully translated everything I gave it. But there I had document-management problems – it would say it could output its translation into a Word document configured for a publisher, but would not actually do so, or do so only partially. I spent as much time wrangling documents as I did actually "‘translating". Eventually, I turned to Google Docs which somehow combined best with ChatGPT (odd, given Microsoft’s investment in OpenAI) and got a script that worked well.

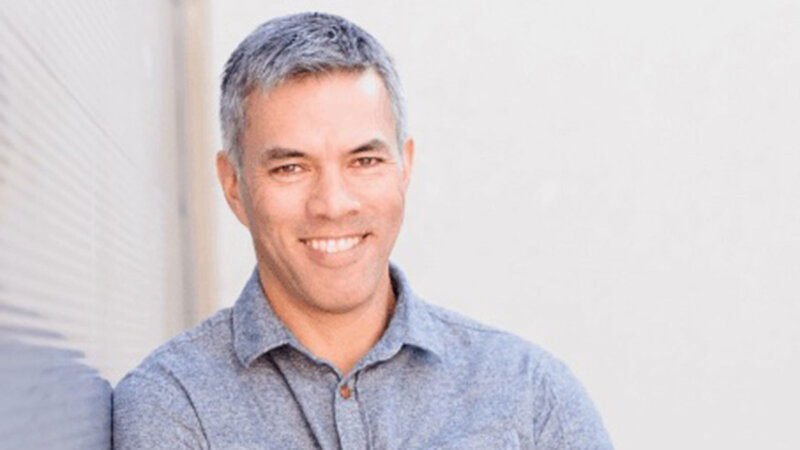

At one point, I asked for the help of one of my fellow AI innovators, Senthil Nathan from Ailaysa. They offer a paid platform that assists authors to do a host of tasks in the creation and publication of their books. Kindly, they also translated my book, using Google’s models.

I sent both my ChatGPT/JAIS "mash-up" and Ailaysa’s translation to Al Arabi, having given it my best shot. It was a huge learning process for me. The publisher told me their editors assessed the translations as being 85%-90% acceptable, requiring less than two days of further human editing (which, however, was predictably essential).

The astonishing learning here is that every author can and should feel enabled to translate their own book, reasonably well, and for free. It’s not perfect, it’s not as easy as just cutting and pasting, and it won’t be appropriate for works of art. But for a business book like mine, where conceptual communication rather than beautiful writing is the priority, it does illustrate that AI truly is an allied intelligence, transforming the way authors can think about reach and recognition, when historic economic models might prohibit them from reaching new audiences.