You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Vive la révolution (du camp)

Will the Olympics opening ceremony usher in a new wave of kitsch French literature?

There is no question that the Olympics opening ceremony was a masterwork of camp aesthetics. With metal band Gojira singing revolutionary songs while suspended from the medieval towers of the Conciergerie palace, a naked Smurf on a giant plate of plastic fruit, and a drag show on an antique 1900 iron bridge, many of us were amazed by this display of kitsch eccentricity. I was surprised, however, that no French media defined it as camp. It was called exaggerated, daring, colourful; but camp, never.

After doing some research, the reason for this became clear: the word "camp" had not been used, it seems, because it’s simply not a word in French. The whole concept of camp is absent from the local literature, culture and even language.

When Susan Sontag’s "Notes on Camp" from 1964 defined the style as “the modern dandyism”, she put words on a fashion movement that was already firmly established in the English-speaking world. Camp had been carried by the queer and drag scenes for a while, and it later bloomed into magnificent, eccentric works of art like the "Rocky Horror Picture Show" or Cher’s entire discography.

In France, though, Sontag’s essay remained untranslated for many years, and the concept remained unknown. When asking around if the term “camp” rings a bell, I receive only perplexed looks, before being asked if it is related to wild camping. If I try to explain it, I find myself struggling. We simply don’t have words for this.

Patrick Mauriès’ 1979 essay "Second Manifeste Camp" is one of the few French books that has been published on the topic. The national bookshop database defines it as “a treaty […] on the anglophone concept of camp, an aesthetic sensibility revolving around bad taste and kitsch”. This barely covers the perfect alliance of excess and enjoyment that is camp.

This striking rejection might be explained by the national preference for "high-brow" art and literature, in a country where looking cultivated is just as important as actually knowing your stuff.

When asking around if the term “camp” rings a bell, I receive only perplexed looks, before being asked if it is related to wild camping. We simply don’t have words for this

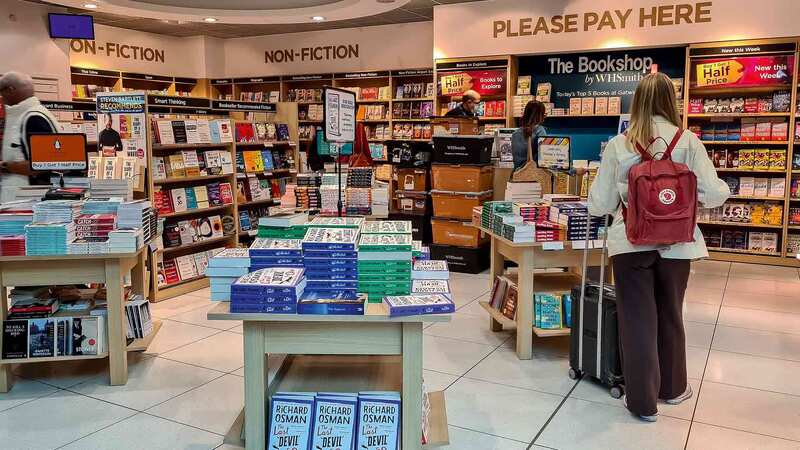

The French book market is a perfect reflection of this. When entering a bookshop in Lyon, Lille or Strasbourg, it can come as a shock that most books share the same white covers. The greatest publishers take pride in the uniformity of their book designs, as plain appearance seems to imply intellectually demanding content. The more monotonous the cover, the more reputable the book. Gallimard’s most prestigious collection, La Blanche or “the white one”, has an instantly recognisable immaculate cover. This, in turn, allows the reader to guess what sort of literary work they’re about to buy. Literature is a serious business, you see.

Colourful styles, on the other hand, tend to be associated with "low-brow" literature. Rich drawings and embossed paper are only tolerated for romance or fantasy. This goes back to the 19th century when illustrated, often kitschy covers were a feature of feuilletons, these serialised novels published in popular newspapers. The cover of your book categorised you as either the Aristotle-reading cultivated élite, or the tasteless plebeians enjoying murder stories. It is ironic, then, that some of these feuilletons became today’s classics, from Alexandre Dumas to Eugène Sue.

The cultural connection between plain aesthetics and alleged intellectual finesse is so strong that whoever questions it faces immediate backlash. This is what writer and translator Bérengère Viennot found out when she tweeted that French book covers were boring. She was immediately accused of bad taste, which in France is equivalent to the deepest moral corruption.

Yet, things might be changing. The French literary scene might be opening itself (very slightly) to some (meagre) eccentricity. After years of remaining in the shadows, Sontag’s "Notes on Camp" was finally translated into French in 2022. The translated title, "Le Style Camp", isn’t of great help to the French reader, who probably has no idea what the word even means. However, this seemingly anecdotal event might spark the recognition of camp in the French cultural world. Patrick Mauriès’ "Second Manifeste Camp" was recently re-issued. French novelist and film critic Pascal Françaix published a three-volume anthology of camp in English-speaking cinema, where he claims “camp is a vital tool to understand the world”.

This long-delayed recognition has found an apex with Thomas Jolly’s eccentric show. And, in spite of far-right and conservative Catholic media being upset about an allegedly blasphemous tableau, it is remarkable that no one in France seemed to disagree with the general aesthetic of the event.

So, is this the year camp finally enters French culture? Will the flamboyance traditionally associated with drag conquer more aspects of the local cultural scene? Are we to see an explosion of ironic, flashy aesthetics and vibrant book covers?

Maybe. But in that case, the concept will need a name. My Francophile friends, I await your suggestions.