You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

What happened to Sad Puppies?

For four years, a group of authors attempted to undercut the ’wokeness’ of the Hugo Awards. It didn’t work.

The Sad Puppies era is arguably the bleakest passage in the history of the Hugo Awards. The Puppies’ campaigns gave rise to smears, vitriol, conspiracy and hostility; they can be regarded as an early skirmish in publishing’s now-pervasive "culture wars", where suspicion, belligerence and an unwavering conviction in one’s own position routinely permeate discourse.

The Hugo Awards, which have celebrated pioneering works of science fiction since 1953, have traditionally — and undoubtedly still are — the highlight of the science fiction calendar, but for a small group of agenda-driven agitators, they represent nothing more than an avenue through which all-too progressive views are disseminated and applauded. There is a particular fringe that laments the apparent "wokeness" of the Hugos, and claims that accolades are not handed out on the basis of quality, but on how politically correct the writing.

This mindset came to prominence most notably in 2013 with the emergence of Sad Puppies, an anti-Hugo faction of writers and fans bent on venting their award-related frustrations.

Sad Puppies felt — emotionally rather than evidentially — that certain demographics — namely straight, right-leaning white males — were being overlooked so that the Hugos could elevate diverse, historically underrepresented voices. This, Sad Puppies seemed to imply, was the only possible reason why certain authors weren’t being given the praise they deserved on the award circuit.

Between 2013 and 2017, Sad Puppies attempted to influence, through the use of a tactical voting bloc, the outcome of various Hugo Awards categories. The group’s goal was twofold: to “restore integrity” to the awards, and to highlight the perceived injustices felt by the Puppies.

From the 1970s, the Hugos’ nomination system involved members of the World Science Fiction Convention (Worldcon) putting forward five “equally-weighted” nominations in each category — Best Novella, Best Novelette, Best Short Story etc — with the five most selected works moving on to a final ballot. Members then used ranked-choice (instant-runoff) voting, numbering their preferences from most to least preferred. Notably, the option to select "no award" was always listed, and essentially treated as a sixth candidate.

This means of voting was considered by most to be fair, inclusive and anti-partisan. However, according to Kevin Standlee, part of the Hugo Awards Marketing Committee, the system had an obvious vulnerability, and could be manipulated with relative ease by someone with the desire to be nominated through underhand means, and the influence to make it happen.

“Anyone can join Worldcon, and doing so makes one a member of the World Science Fiction Society," he says. "The minimum cost — what we call a ’supporting membership’, which gives one voting rights but not the right to attend the convention — was generally at the time $50, although the actual price is set by each year’s Worldcon. A known exploit of the system was that, particularly when relatively few people participated, a sufficiently determined minority acting in co-ordination could "pack" the ballot with their candidates." And exploit the system in this manner is exactly what Sad Puppies did.

The rise of Sad Puppies showcased that for some, difference of opinion can easily be misinterpreted as outright oppression

The group and its acolytes stated that their animosity towards the Hugos was a response to the perceived favouring of left-wing authors and their writings. Sad Puppies claimed that not all sci-fi works were being granted the same level of consideration by Worldcon members, and suggested that authors with certain political stances were championed, while those with opposing views were either suppressed, or roundly ignored.

The group, therefore, decided to take matters into its own hands.

Initially led by author Larry Correia — and subsequently spearheaded by Brad R Torgersen, Kate Paulk and Sarah Hoyt — the Sad Puppies’ campaigns used social media and blogs to great effect to let loose rallying cries, encouraging those of the same mind to pay for Worldcon membership and nominate a batch of selected books – many of which, it’s worth pointing out, were written by the campaign’s leaders.

As a result, a number of relatively obscure, Sad Puppies-backed books ended up dominating some Hugo shortlists – something Standlee, and the majority of Worldcon members, actively opposed. “The only candidates on the ballot were deeply opposed by nearly all of the members. They had little choice but to vote for ’no award’,” Standlee said.

Sad Puppies’ campaigns were announced for five consecutive years — though the 2017 iteration never actually materialised — and were brought to a conclusive end when, in 2017, the rules around Hugo nominations were changed, limiting the power of bloc voting.

An author promoted by Sad Puppies during one of the campaigns, who requested anonymity, explained to me their view of Sad Puppies’ inception, and what the group hoped to achieve through its actions. “A cabal of insiders had openly influenced the Hugo Awards to favour first a leftwing political agenda, and secondly Tor [the publishing company] authors,” they claimed. “In short, authors were receiving awards not based on the merit of the work, but on their political affiliation, or their relations with a powerful New York publisher. The awards were no longer awarded for writing, but for political correctness and patronage."

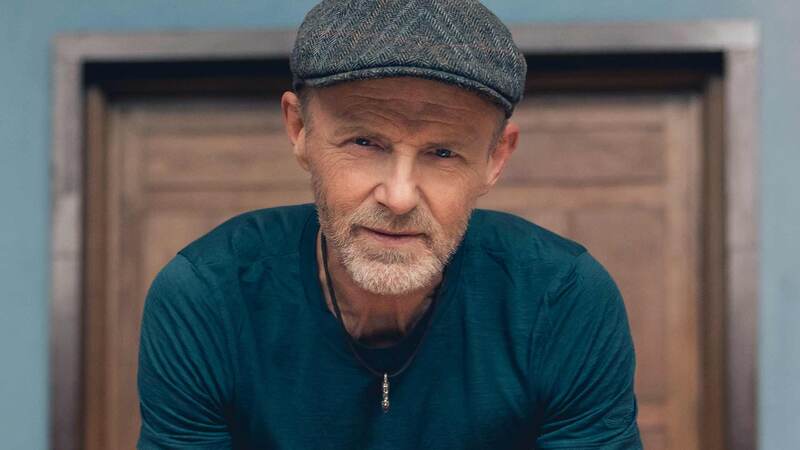

This is, of course, just one perspective on Sad Puppies’ motivations. Neil Gaiman, winner of seven Hugo Awards, has a very different interpretation of what likely catalysed the group’s exertions. He says: “I remember reading in, what, 2014 or 2015, about these people who were trying to game the Hugos, and didn’t seem to like what science fiction had become. I thought they were people with a chip on their shoulder who probably weren’t good enough writers to win awards without doing something like this. If you want to be a good writer you have to put in the work, and these seemed like people who had chosen to be aggrieved rather than do the work. They wanted to win, and for foreign books and women to become much less prominent. The people who seemed to be shepherding the majority of the ’Puppies’ around wanted Hugo awards, and it was easier to get a bunch of people to pay for supporting memberships and vote for them than it was to write stories good enough to win them.”

What ultimately stimulated Sad Puppies to launch its initial campaign — be it bitterness, egotism or genuinely held beliefs — is open for discussion, though the general consensus seems to be a regressive cocktail of toxic masculinity and resentment. The group’s achievements, or lack thereof, are also contested. The prevailing narrative is that the Sad Puppies’ campaigns were unsuccessful, though the derailing of the 2015 Hugos — which saw an unprecedented five categories given “no award” — was hailed as a victory of sorts by the group.

The anonymous Sad Puppies advocate we spoke to fully disputes suggestions that the campaigns should be branded failures. They are adamant the Hugos remain just as unrepresentative and biased as they considered them to be in 2013, and they believe Sad Puppies played an important role in raising awareness of this apparent issue.

“No, it was not unsuccessful. The campaign(s) proved to any onlookers who care to look that the modern Hugos are awarded solely for reasons of political correctness. A casual perusal of the lists of candidates and winners over the past four years is a sufficient confirmation of this. The Hugo Awards, in effect, burned themselves to the ground for the sole purpose of avoiding my work being recognised. The fans had selected an author that the insiders did not prefer – despite that I myself was a Tor author at the time. Those who hoped sobriety would prevail, and the Hugos return to the dignity they once knew, had their hopes dashed.”

For Sad Puppies apologists, the fact that the Hugos felt compelled to alter the nominations process was taken as additional validation that they, and the anti-woke authors they supported, were being censored and excluded. For the majority, however, the Hugos’ move was simply the most viable means of reclaiming the awards, and stopping disillusioned, paranoid saboteurs from disrupting them further.

Post-2017, the Sad Puppies collective faded away. Those who supported the campaigns at the time likely retain the view that the Hugos are some kind of leftist propaganda, while fans of the awards — of which, it goes without saying, there are many — are undoubtedly pleased that the Hugos prevailed, and relieved that Sad Puppies’ relevance eventually waned.

Works of science fiction, as with any piece of art, will always spawn differences of opinion. Determining the quality of a book is, and forever will be, subjective, and so awards will habitually be contested and debated.

The rise of Sad Puppies showcased that for some, difference of opinion can easily be misinterpreted as outright oppression. The group’s demise, meanwhile, indicates — some would say mercifully — that minority views built on foundations of contempt and disdain have a limited shelf life, and will eventually slide into, if not complete obscurity, then something resembling it.

For Gaiman, the Sad Puppies affair is something he’s more than happy to see the back of. Indeed, he ended our correspondence with a rather sombre analysis of those who put their weight and reputations behind Sad Puppies’ campaigns: “Perhaps they were trying to make up for something missing in their lives.”