You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

What is the Royal Society of Literature for?

Recent controversy around the RSL raises questions about its purpose.

In recent weeks, a furore has emerged at the Royal Society of Literature after decisions by the society’s leadership body sparked contention among the society’s fellows. Founded in 1820 under the patronage of King George IV and set up to "reward literary merit and excite literary talent", the RSL, based in Somerset House, has long been a bastion of the greatest writing from the UK. Lately, however, the society’s history of exclusivity – and its plans to address this history – have come under fire. Foremost in the public’s attention is a planned change to the fellowship election process, whereby, drawing on the success of the RSL’s ‘40 Under 40’ initiative last year, the society will invite readers and writers throughout the UK to recommend potential new fellows for election.

Several existing fellows of the RSL, including Ian McEwan and previous president Marina Warner, have expressed dismay at these proposed changes to the selection process. "There is a lot of turbulence," Warner told the Observer in January. "It is a question of a lack of respect for older members and a loss of institutional history, which was something fellows cherished."

In the face of this dispute, certain essential questions arise: what is the purpose of the Royal Society of Literature? Is it an institution that should venerate age and tradition, or should it be for everyone?

An answer to this last question may lie somewhere in between. The RSL receives most attention in the media for its selection and celebration of the greatest writers in the UK (to be considered for an RSL fellowship, "writers must have had published or produced at least two substantial works"), but a large part of its work involves outreach programmes in schools and prisons, with the organisation working to spread a love of literature irrespective of readers’ backgrounds. As a charity, the RSL has a programme of talks, discussions and readings, and it co-ordinates book donations. As it states on its website, the RSL wants "everyone [to] feel that literature is for them’’.

Is the RSL an institution that should venerate age and tradition, or should it be for everyone? The answer may lie somewhere in between

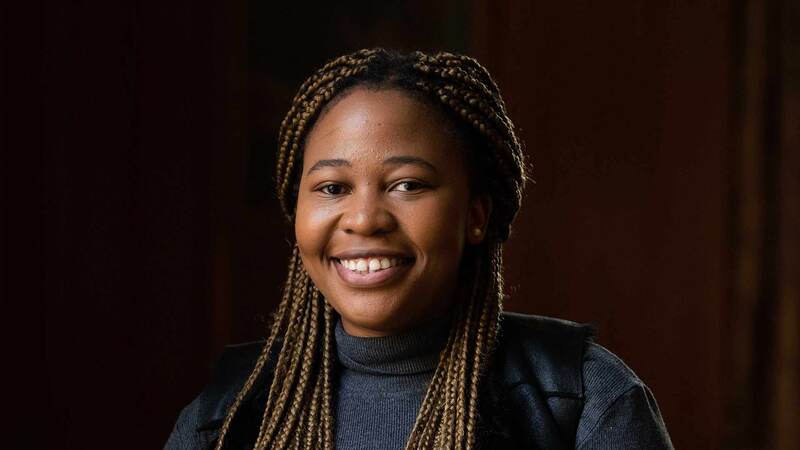

And so, the RSL has two functions: to identify and celebrate the very best literature, and to foster an appreciation of literature in everyone. Much of the recent disagreement revolves around how much these two functions should mix. According to Bernardine Evaristo – the current president of the RSL, whose role is largely symbolic, but who has nonetheless faced much of the recent crossfire – the society "needed to change". She feels that it has needed to become one that is "for all writers, rather than traditionally writers who are white and middle class" – and that this needs to happen through the fellows whom the RSL elects.

The difficulty here is that an RSL fellowship is not for all writers: we have the writers’ trade union, the Society of Authors, for that. The currency of this award is the very exclusivity and elitism that the current managerial board is keen to confront. Indeed, this debate highlights an issue within the book industry at large: can we square inclusivity with excellence? The literal meaning of elitism is choosing, and so much of what happens within publishing is a matter of selection. Walk into your nearest bookshop and notice the array of books proclaiming slogans such as ’Book of the Year’ and ’Prizewinning Author’, and broadcasting endorsements from high-profile writers across their covers. This is an industry that revolves around the logic of superlatives, and the literally elitist project of choosing the ‘best’ debut writer, or the ‘best’ novel. Literature may well be for everyone, but not all literature.

The Royal Society of Literature has such cultural cache because it does some of this work of choosing for us: readers, when faced with an overabundance of choice, often like to go for books recommended by experts. When writers become RSL fellows, their books sell more; Laline Paull told the the Guardian recently that her fellowship gave her "a bit of solid ground under my creative practice", and this rests in large part on the ringing institutional endorsement that an RSL fellowship entails. Trained by the logic of publicity to notice such accolades, book-buyers are often swayed to make a purchase when they know that the establishment thinks a given book is ‘good’.

All this is to say that the elitism of the fellowship – like other ‘lifetime achievement awards’, such as the Nobel Prize – is both its trickiest and most valuable characteristic. The RSL can be for everyone, but an RSL fellowship needn’t be: in its rigorous selection process that requires existing fellows to elect nominated writers, this position is rightly one of the most prestigious accolades a writer can achieve. However, doubling down on efforts to ensure that the selection process truly rests on writers’ merit is crucial, as is the RSL’s acknowledgement that "self-selecting groups can present a challenge to diversity".

If the demographic make-up of the fellowship is skewed – and it is – then this is a symptom of a wider challenge: becoming a writer is a privilege that isn’t available to everyone. One possible solution is investing more in programmes and awards for writers along the road to success, such as the RSL’s initiatives to support emerging writers, including the V S Pritchett Prize and RSL Giles St Aubyn Awards. But support for debut writers isn’t enough. Excellence develops through sustained effort beyond a writer’s debut book, and while under-represented authors are increasingly being celebrated as new writers, there currently aren’t enough initiatives in place to support these authors beyond this initial hype.

The RSL can be for everyone, but an RSL fellowship needn’t be: it is rightly one of the most prestigious accolades a writer can achieve

Nevertheless, programmes to even the balance, such as creating a quota of fellows under the age of 40, risk diluting what an RSL fellowship means. The fellowship isn’t about potential, but achievement. For this reason, the RSL fellowship will become more diverse not just when diverse writers are acknowledged as debut authors or at an early stage in their career, but when they are actively supported by the industry to reach their potential. In this context, elitism won’t need to be a dirty word. By selecting the greatest writers, the Royal Society of Literature sets high standards for literary production and champions books that live up to those standards. This has real and lasting value. But the RSL and the industry as a whole must also work to improve the pay and support systems that will allow writers everywhere, of every background, to consistently produce their very best work.