You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Why the Barnes & Noble sale may help US publishers buy better books

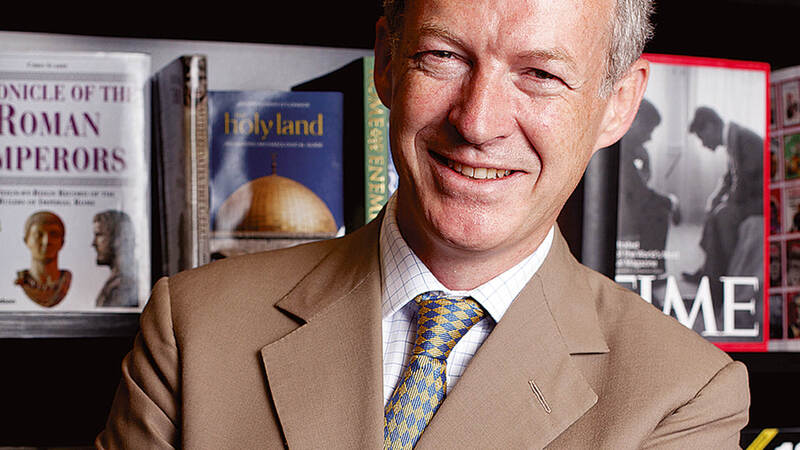

When I read that Elliot Advisors and Waterstones will buy Barnes & Noble, naming Waterstones c.e.o. James Daunt as Barnes & Noble c.e.o., I thought it hopeful for many in book publishing. Daunt’s success in turning Waterstones around may speak for itself, and pouring capital into 627 long-struggling B&N bookstores might just be what publishing needs.

I also sensed that others might not think that solution to be book publishing’s idea of salvation.

We can only hope that this promising B&N news might change the fact that many feel fatigue over the current state of major trade book publishing. The B&N purchase might help mitigate external pressure from online retailers on physical outlets, for physical retail has not yet fully risen to those challenges. Here are just a few that agents and editors have been grappling with in the US:

Retailers pressure publishers

The retail landscape in book publishing has put tremendous pressure on book publishers to continually publish successfully. Bookstore closings, and how tough Amazon has been on retail and publishers, has caused bookstores to become far more cautious. Bookstores are only ordering to net on however many copies of an author’s last book sold. This inevtiably means that, regardless of how many copies a publisher might have printed on an author’s first book, their second publication will be much quieter if bookstores will only carry as many copies as previously sold.

Fewer books, imprint comings and goings

In response to this retail landscape, book publishers are now buying and publishing more selectively, making it harder for agents to get books sold. As an agent I now have to think to myself: will publishers buy this because it is a manuscript represented by my tastes or will the publisher purely make a numbers-based decision?

It has become something of a frustrating mantra across those on the publishing side of the industry: “Fewer, bigger books.” Publishers are focusing on republishing established or big-name authors, such as Michelle Obama’s Becoming and future Obama books, betting that a number one bestselling author’s next book will also be a bestseller.

Penguin Random House also folded up their Crown Publishing division, the very same imprint that brought the Obama money/success into PRH in the first place. For PRH to then purchase a majority share in Sourcebooks for interest in particular aspects of their list, seems odd. Many feel that PRH has already grown too big in acquiring many imprints, thereby creating a company with too many overheads in a small margins business.

Making big bets on debuts

On the other extreme, publishers are looking to debut authors with no prior book publishing baggage/track record. It is easier for an editor, receiving a debut submission, to make the case to their editorial board to acquire that book. The editorial board can really only evaluate a debut on a purely subjective basis, because no prior sales data exists for that writer.

A debut author probably have a 50/50 chance with a publisher, much greater than a previously published author with a damaged sales track record. And agents love that publishers now tend to overpay for debut fiction due to their high hopes. Debut fiction was historically a quieter sector of the publishing business, because many of these debut titles still end up underperforming—without the type of platform/built-in audience often seen in non-fiction. Only one or few debuts will live up to publisher expectations, but they will carry the list for the other exaggerated debut bets made by publishers.

Carefully buying fiction

So how do publishers look at ways to safely evaluate the business decision behind buying fiction without racing to either extreme? I recently talked with Christopher Kenneally, of the Copyright Clearance Center’s Beyond the Book podcast, about how the state of the retail landscape has forced publishers to change the way in which they think about acquiring all of their fiction. It is no longer just about the quality of the writing and relevant writing experience and credentials—now publishers are looking for fiction writers that have built-in audiences and platforms.

This mirrors the way in which non-fiction is acquired by publishers—based on the size of an author’s platform. Many books are being born out of the podcast storytelling space; others from social media influencers; others from those with big subscriber bases. An agent can show publishers that such an author has an engaged built-in audience or subscriber base. While the manuscript still needs to speak for itself, a big part of my job has becoming finding authors who excel at these online methods.

Hope for book publishing

Some dream of a time in book publishing that is long gone. Others will say it is too late to return to the old methods. Before so much of book publishing was data-driven by sources such as NPD Bookscan, it was far easier to build a new or mid-list author publishers believed in. Publishers could continue to publish such authors across a number of books until they became household names.

The current reality of the retail landscape has caused this aspect of mid-list authors in book publishing to bottom out. Book publishing is so driven by the numbers and salesforce that to return to a completely editorial method of acquiring books would seem absurd. Then again, many who were around to see book publishing back then will say it was a better time in book publishing, when books were simply bought for editorial reasons. There were more three-book or four-book contracts and fewer two-book or one-book contracts.

Perhaps, with the health of Barnes & Noble renewed and less of a reliance on the numbers of book publishing, we might not be too far off a mini-renaissance.

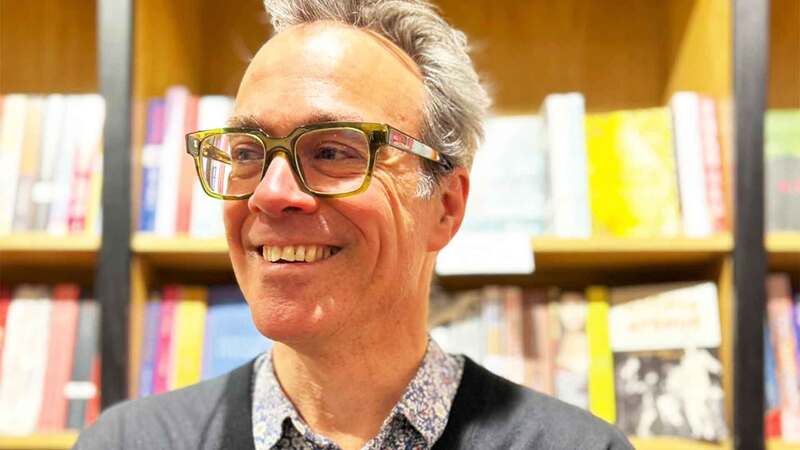

Mark Gottlieb is a literary agent for the Trident Media Group who has represented several New York Times bestselling authors, as well as optioned and sold numerous books to film and TV production companies. He previously ran the agency’s audiobook department, in addition to working in foreign rights.