You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

With AI for kids, collaboration is key

AI can be problematic in children’s literature… unless we use kids as co-creators.

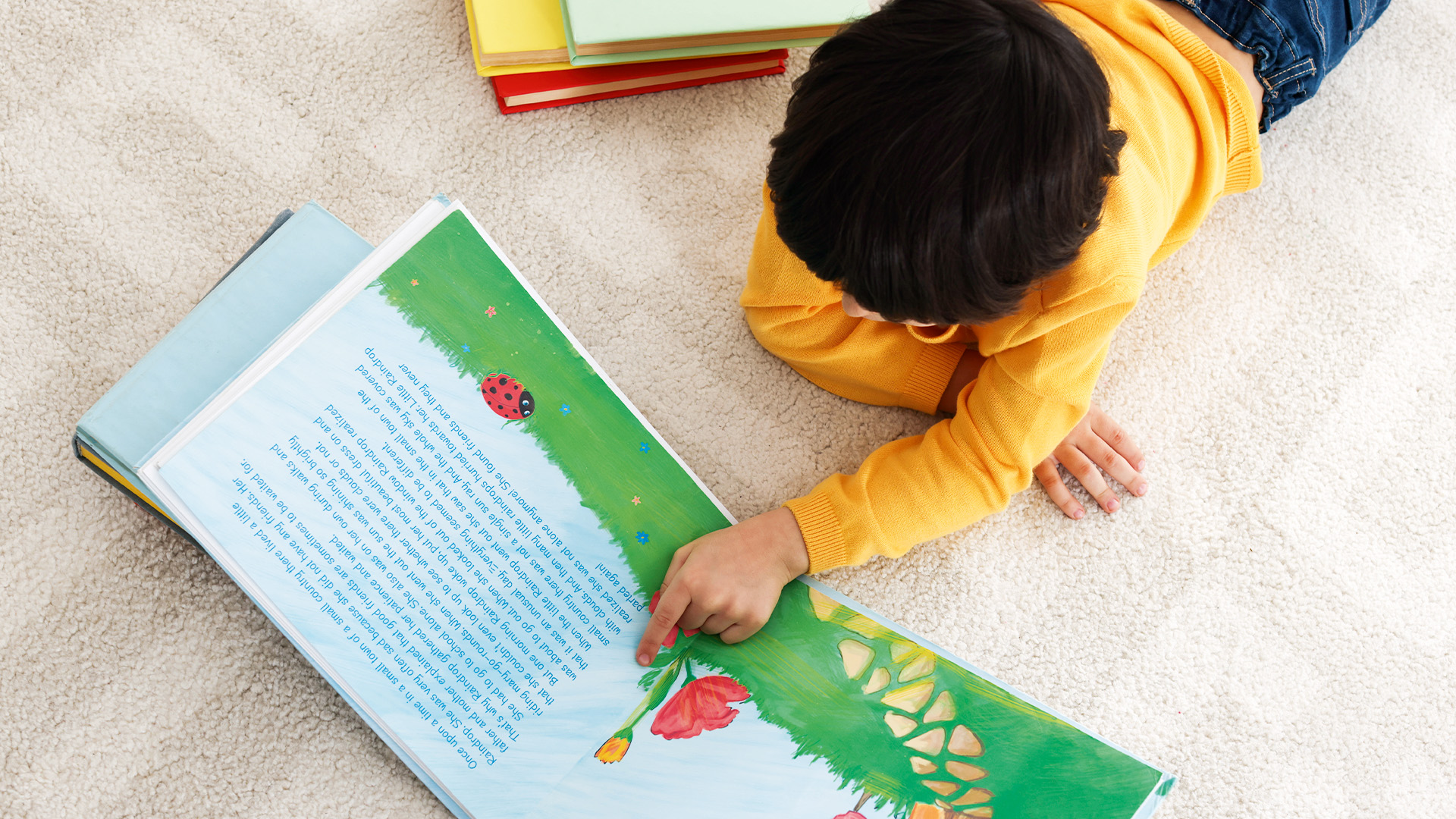

We find ourselves at the precipice of a transformative reading era: AI tutors are entering kids’ classrooms and detailed parents’ prompts generate unique bedtime stories. The prospect of AI as the new Roald Dahl is both exciting and scary. How can we use all the AI innovation to augment children’s story worlds?

My first prompt to chat.openai.com was a request for a personalised children’s story: “Write a bedtime story about Natalia Kucirkova for a four-year-old boy.” I got an attention-grabbing opening “Once upon a time, in a cozy little town, there lived a sweet and curious girl named Natalia Kucirkova. Natalia had bright, sparkling eyes that were always full of wonder.”

I have been studying digital personalisation – the use of personal data in digital texts – for some time. I know that the use of personal names in texts is an effective marketing technique to grab readers’ attention, and yes, a story about Natalia captured my interest. I began thinking about machines scraping personal data and the possibilities for AI to generate deeply personalised stories to get children’s attention: not just about Natalia but with Natalia as the main character, with personality traits based on my social media interactions and likes based on my shopping behaviour. For children, deeply personalised stories about them and their friends or family members could be produced on demand, with a few clicks.

Adult ideology is reflected consciously and unconsciously, in the texts the AI generator produces and illustrations it generates. As AI is being adopted for classrooms at speed, children’s views get further overlooked

Ethical questions

The current AI legislations are too broad and the protection of children’s digital rights too vague to address the Pandora’s box of legal and child psychology issues associated with such stories. Publishers and booksellers are stewards of values, they play an important role in shepherding the ethical principles as the AI capabilities advance. Many publishers worry about the implications of these rapid changes for acquiring and developing content, rights management or long-term publishing strategy. Moral and philosophical questions abound.

The UNESCO’s recommendation on the ethics of AI set the normative framework to navigate the ethical jungle, with some core principles, including transparency, human oversight and determination. These guardrails must be implemented into children’s AI stories by design. What this will look like in practice is not clear yet, but here are some possibilities.

Centre the child

Consider the booksellers’ role in quality assurance of AI-generated texts. Just like the Internet, AI was not developed for children. Adult ideology is reflected consciously and unconsciously, in the texts the AI generator produces and illustrations it generates. As AI is being adopted for classrooms at speed, children’s views get further overlooked.

Yet, decades of child-centred research (e.g. studies by Alison Druin and her group) have shown how important it is to think of children as design partners rather than just users of technologies. Children’s design ideas are implementable and can enhance both the development and use of new technologies.

Adult ideology is reflected consciously and unconsciously, in the texts the AI generator produces and illustrations it generates

Publishers and booksellers can position children as creators rather than consumers of AI. Imagine an AI story generator based on Roald Dahl’s stories and Character.AI with Matilda Wormwood, Mrs Twit or Augustus Gloop for children to experiment with. Booksellers could facilitate children’s authorship with AI story-generators trained on high-quality stories, with children’s favourite story characters. In the future, the works of any children’s author could be used to feed such story generators.

Educational data

Many indie authors, parents and educators are already using free generators (e.g. Character AI for story characters) and image generators (e.g. the one by Shutterstock), to create stories for children. With “Creative Helper.AI” and “AI Pet generators”, children can develop relatable story characters and make up stories that influence their story worlds. Publishers could collaborate with educators and educational experts to train AI generators with pedagogical goals and educational content.

By providing high-quality resources that encourage collaboration and joint reasoning among children (group activity guides, collaborative projects that require children to work together to create plot lines or story characters), AI story generators could be trained with educational data and parameters supplied by the publishers.

The reality

Needless to say, the creation of AI story generators is a Janusian process where the positives and negatives simultaneously cancel each other. The flipsides of digital personalisation are many, and the AI story-generators directly touch the psychology processes of self-centredness and confusion around a child’s sense of self. Without any human editor mediating the space between the child and today’s A`i authoring tools, the possibility of harm is very real.

Our ability to address AI threats is greater by directly engaging with them. As any children’s publisher knows, the production of high-quality stories is about much more than content generation. The depth of human creativity and expertise that goes into the production of high-quality children’s bedtime stories will be more apparent if booksellers facilitate new collaboration models between authors, children and AI.