You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

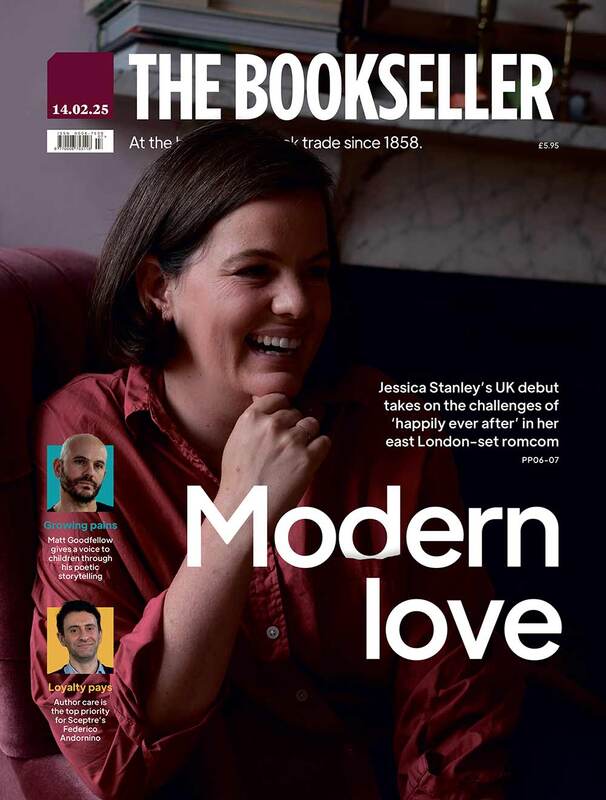

'Words become powerless': Ukrainian publishing, 42 days on

As international book fairs ramp up, Ukrainian publisher Kateryna Nosko explains how colleagues and peers continue to write, publish, sell and salvage their work in the midst of war.

It is the 42nd day of the war, and we continue living in the traumatic landscape. Sometimes this landscape shakes even more, such as when we and the whole world witnessed the photos of the Russian crimes in Bucha and Irpin, the Kyiv suburbs. After this, words become powerless. What arrives is a state of numbness.

In this sense, the Ukrainian stand at the international book fairs manifest this desolation. The organisers say the idea of the empty stand in Bologna shows that Ukraine is at war, and the publishers are saving lives: their own and the ones of their loved ones. Indeed, today such a thing as a trip to an international book fair is blocked. Still, there is a feeling that publishers and cultural agents, who continue working or are already abroad, should turn the empty stalls into a platform for loud Ukrainian voices that represent the contemporary Ukrainian cultural and book publishing sectors.

Because of the impossibility of talking about war when it unfolds in one’s country, images with short captions seem helpful. A week ago, a comic strip was released by Borys Filonenko and Danyl Shtangeev called "How to protect yourself and save others when you are a terrorist leader". The comic has 10 pages and resembles an instruction manual. All images are low-quality and grainy, as if from soviet handbooks. Filonenko wrote the text in an hour and a half after seeing the stage during a concert rally in Moscow’s Luzhniki where Putin spoke on 18th March. The scene resembled a cage and became a key element of the comic. The work took a week in total, but only because there is not enough time for making a comic nowadays. While the authors were working, the missiles fell on Western Ukraine: Lviv, Lutsk, Rivne, Khmelnytskyi. Shtangeev’s mother called him for the first time in two weeks, but the call was only eight seconds long as she was in Rubizhne, right on the frontline. During this time, the Mykolaiv Regional State Administration, where some people were staying, was bombed and destroyed. Our friends – artists from Mariupol – from whom we’d heard almost nothing since the beginning of the war were finally found. "We are all waiting for a long, crowded, comprehensive tribunal over the leadership of RF and all the accomplices and supporters of the war," Filonenko summarises.

There is a feeling that publishers and cultural agents, who continue working or are already abroad, should turn the empty stalls into a platform for loud Ukrainian voices.

Meanwhile, with help our publishing team has managed to rescue some book stock from Kyiv and Kharkiv. In particular, we rescued copies of art book KYIV by Sergiy Maidukov, by an artist who often creates illustrations for the New Yorker. He likes to draw from life in the city, but now it isn’t easy to manage. On the streets of Kyiv, as soon as you get a camera or a tablet out, the Territorial Defense comes up to you to identify who you are and why you are recording. This is necessary to determine whether you are working as a saboteur or enemy reporter.

Our office, where some of the books by Sergiy Maidukov are stored, is located in the Kyiv historical city centre, in Podil, on the right bank of the river. On a regular day before the war, we would put a key from our office in our pocket, and we would take the number of books needed for delivery and bring them to the post office – a straightforward set of actions. During the war, all of this doesn’t seem as clear anymore. Firstly, only one team member remained in Kyiv – our designer Dima Frolov. However, he didn’t have a key. Apart from a neighbour on the left bank, no one did. This made the task even more difficult since the bridges are blocked, and those that remain open are dangerous to cross. Still, this hadn’t stopped Frolov from going to the left bank, spending three hours in traffic while all the block-posts checked the documents and the car tank several times. The next day he managed to send the books to Western Ukraine.

When we published KYIV by Sergiy Maidukov last year, Maidukov said that the book was his declaration of love for Kyiv.

Several days ago, the Russians were pushed away from the Kyiv region. So, Kyiv citizens are gradually returning to the capital, even though the government says there is a significant death threat. The people are coming anyway, a remarkable testament to their love for Kyiv.

Summing up this story about the evacuation, I want to say that when the books finally arrived in the west of the country, in theory to a "safer place", that night, not far from the storage where we put them, the missile struck an oil depot. Neighbours’ windows flew out, but no one was injured. A few kilometres from the explosion, the books were also not damaged. I realised that wherever we looked for quiet places, it was still dangerous everywhere.

Yet, people keep ordering books online, and there are some open bookstores. We, in turn, began to send the orders where delivery allows. However, in my last column here, I wrote that we were not planning to deliver the orders yet. We decided to transfer the proceeds from the book sales to two charitable organisations: the Social Adaptation Complex, where adults with mental disabilities live, and Sirius – the biggest dog shelter in Ukraine.

For the first time during the war, we managed to print a stock in Ukraine. Brave printing staff in Kyiv have finished printing and stitching our new book Conversations about Architecture with Oleg Drozdov and Bohdan Volynsky, which was interrupted by the war starting in February. Unfortunately, the most powerful printing houses are located in Kharkiv, which is in the East of Ukraine, and they cannot operate since the city is constantly under shellfire. Recently, the world-famous Ukrainian poet and writer Sergiy Zhadan came under fire in Kharkiv, which he announced on Facebook. Yet, this hasn’t stopped him from volunteering and going to the city’s most dangerous areas. He writes about Kharkiv nearly every day. One day, he said that Kharkiv residents were cleaning around their houses, raking glass and bricks, because they were used to the cleanness of the city. In the same way, we in the publishing industry, strive to continue doing what we are used to.

Translated from Ukrainian by Daša Anosova.