HarperCollins and AI: a brain-training deal to watch closely

This week, HarperCollins became the first of the big trade publishers to agree to a licensing arrangement with a company developing artificial intelligence (AI). It won’t be the last. As is common in the books business, the pattern set by an early mover will likely be followed by the rest. So we should watch this closely.

The mood music is pretty positive. The Harper deal—for a limited number of backlist non-fiction titles—sees the opting-in author and publisher receive $2,500 each for a three year-licence that will be used to improve a large language model (LLM). Training the brain, as some would have it. The arrangement includes “guardrails”, meaning users will not be able to get access to more than 200 consecutive words and/or 5% of the book’s text, maintaining the integrity and value of the originating work. In turn, the AI licensee has agreed not to scrape text from piracy websites and to act against infringement.

The deal appears to be in line with positions taken both by the UK Publishers Association and the Society of Authors, the latter having called for “explicit, specific consent from the author” when content is to be ingested by the machines.

In the US, the powerful Authors Guild has backed it, posting a short comment piece about the nature of the deal and why it approves—even though it quibbles with the 50:50 split. Indeed, the AG praises HC, alongside Cambridge University Press, for recognising that author permission must be sought first, and in this case on an opt-in basis.

Concerns remain over HarperCollins’ deal. There is a secrecy around it that has made some feel uneasy

Moving to a regime of licensed use gives authors the power to say no or to insist on limits, says the AG. The Harper deal puts a framework around that, but also makes clear that this is extracurricular. “HarperCollins acknowledges that the use is outside of the original publishing agreement by seeking authorisation through a separate agreement providing flow-through payments so that the authors’ shares are not applied against their advances.”

None of this detracts from the harms of copyright theft, with litigation in the US ongoing. Licensing is a way through that thicket, particularly if, as in this case, it comes with additional vigilance. A decade ago publishers went to war with Google for taking their material, and lost the case. If we can avoid that here, all the better.

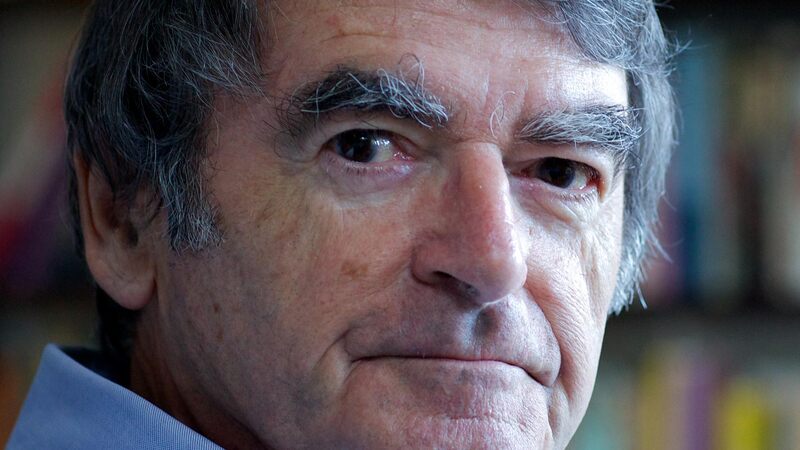

Some concerns remain. There is a secrecy around this deal that has made some feel uneasy. We know of it only because one author, Daniel Kibblesmith, posted about it with his one-word verdict: “Abominable.” We do not know the name or background of the tech company with whom HarperCollins has cut the deal—though it has since been reported as Microsoft. We do not know how the compensation amount was arrived at, what it totals in its entirety (for Harper), and whether agents were consulted on the level—though the Kibblesmith posts suggest there is no room for negotiation.

Despite these qualms, HC can hardly be criticised for delivering the kind of deal the industry has called for. As to what happens once the brain is trained, that’s a question we all must face together.