You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Harry redux

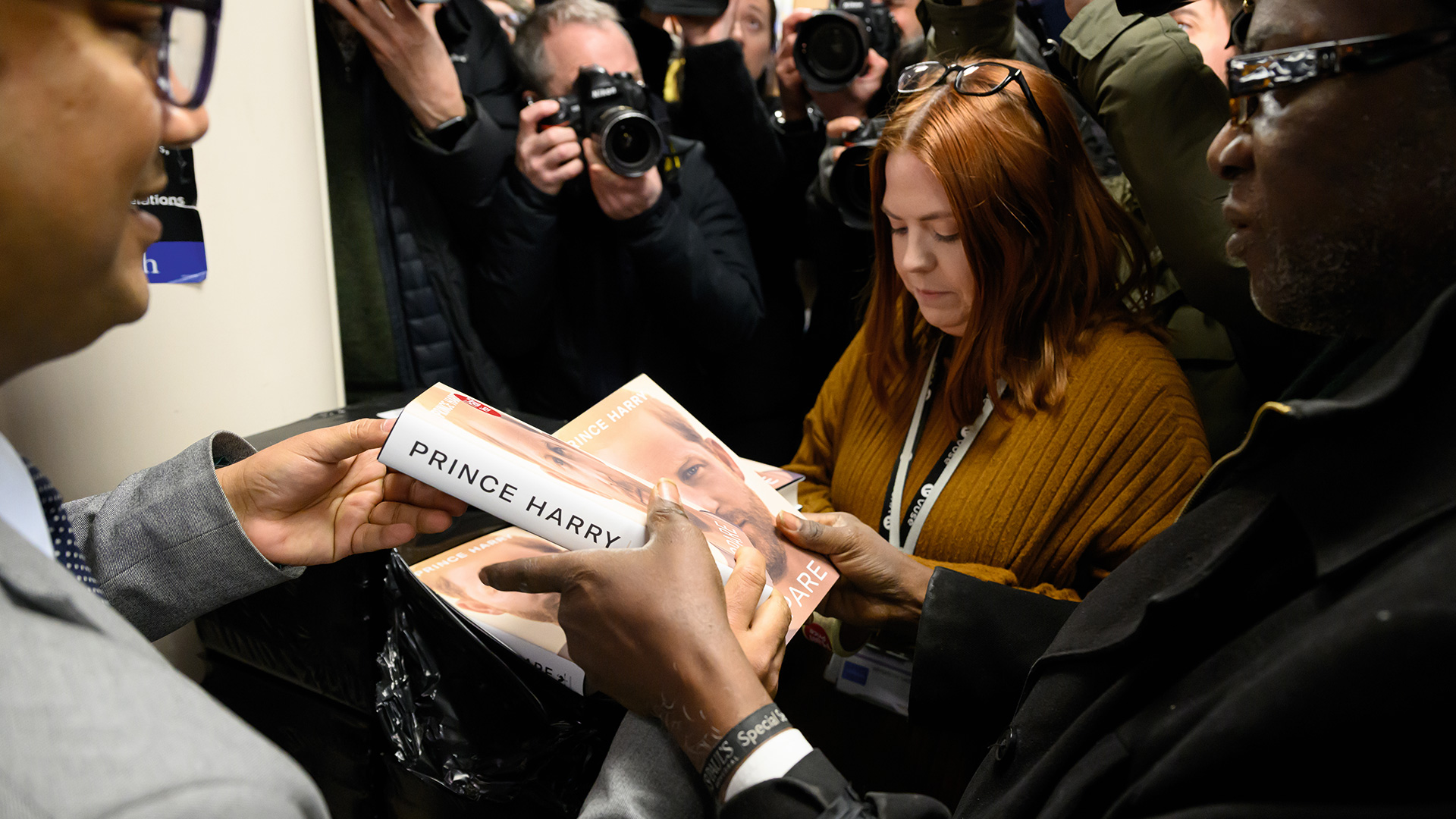

If you can spare a few minutes, here are some important numbers. Viewers worldwide spent 82 million hours watching the first three episodes of the “Harry & Meghan” Netflix documentary over its first four days; Prince Harry’s interview with US broadcaster Anderson Cooper on the CBS show “60 Minutes” saw 11 million viewers tune in; the audience for ITV’s “Harry: The Interview”, hosted by Tom Bradby, peaked at 4.6 million watchers. And last but definitely not least, this week Harry’s memoir Spare sold 400,000 copies across all formats (including pre-orders) on its first proper day on sale in the UK.

In print terms, Spare is not quite yet a record-breaker. We will need to wait until next week, when Nielsen releases first-week numbers for hardback book sales, to crown it. And even with its strong beginning, it has a bit of a way to go. The fastest selling non-fiction book since records began (around 2000) was Pinch of Nom, at 210,506 copies, with the fastest-selling memoir Sir Alex Ferguson’s 2013 My Autobiography at 115,547 (all hardback numbers, and the latter before pre-orders were a big thing). Most recently the book of the play Harry Potter and the Cursed Child débuted on 847,886 in 2016, while the last in the defining children’s series Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows holds the record for the biggest first week of all time, on sales of 1.84 million. It also remains to be seen how the 400,000 breaks down: perhaps half are from digital sales, another third in pre-orders, with the Nielsen figure likely to be closer to Pinch of Nom than the other Harry.

Big event books don’t come around so often that we can be blithe about their overall worth to the market; neither should we pretend they create themselves

Nevertheless, with Waterstones reporting brisk business on the day, as well as strong pre-orders, and indie booksellers more generally noting a surprising level of interest in the £28 hardback, publisher Penguin Random House will believe that its multi-million pound/dollar investment in the Sussexes has been largely justified.

“We always knew this book would fly but it is exceeding even our most bullish expectations,” Larry Finlay, managing director of PRH’s Transworld, said this week. And good for him. Big event books don’t come around so often that we can be blithe about their overall worth to the market; neither should we pretend they create themselves. No launch strategy survives for long contact with the real world, but in holding its nerve over the embargo despite the leaks, getting enough copies printed and into stores, as well as managing Harry’s time and broadcast commitments, Finlay and the wider team deserve all the plaudits. The book’s title alone merits a Ronseal award.

What happens next is almost more interesting than what’s already taken place. Harry’s book numbers are big, but a smidgen compared to the Sussexes’ wider reach on social media and elsewhere. Big books tend to sell outlandishly well and for longer than expected because they bring with them new audiences. Most people do not buy books in this country—at least not regularly. So when they do, let’s be glad of them and make sure we welcome them to the fold, however they choose to consume this particular title. We cannot spare them.