You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Honey vs money

Book publishers do pretty well these days with their routes to consumers having improved over the past decade.

Some years ago at the British Book Awards, I had a chance encounter with one of the editors on the Editor of the Year shortlist. As they had not won, I offered commiserations – for context this was just after the colouring-in boom. “I have the misfortune of publishing books with words in them,” they said in a response that amused me then, and still does today.

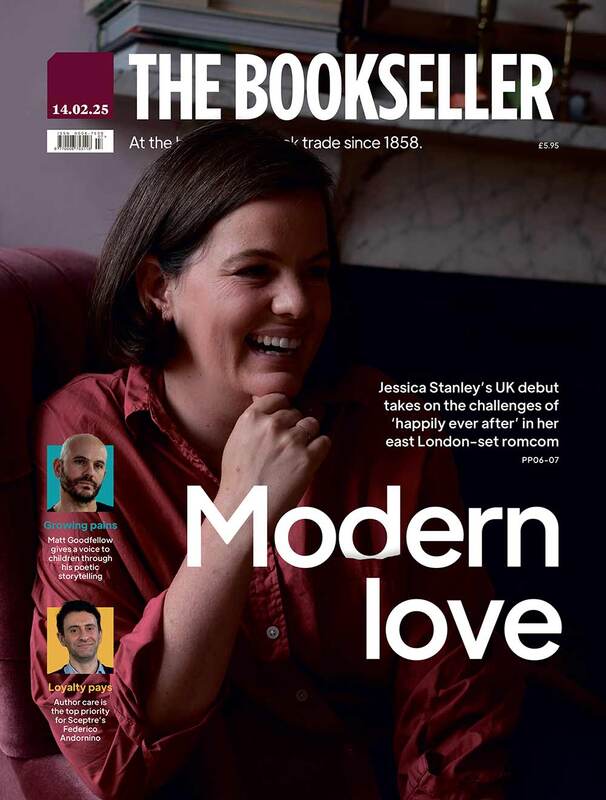

I was reminded again of this take, having read the interview in this week’s issue of The Bookseller with David Fickling, founder of his eponymous independent children’s business DFB. I’ve aways thought of Fickling as the publisher’s publisher. His contribution to children’s reading is immense. If I asked ChatGPT to conjure up an image of a book publisher this is what it might come up with. Bow-tie, too.

Fickling has worked across the business, but now says that independence is “probably the most important thing” about DFB, enabling it to invest in penmanship over time in the way its bigger rivals cannot. He continues: “I don’t mean this rudely at all, but the very large corporations are no longer publishers – bits of them are publishers, and you meet them, brilliant publishers – but the whole thing is something else. As the size grows, money becomes the only thing everyone can agree with, the system takes over.”

I don’t suppose the editor at that Nibbies back in the day meant to be rude either, or disparaging towards the recipient of the gong that year, and yet, I cannot help but think that both perspectives underappreciate the importance of a diversified marketplace and of the different actors in this space.

From Murdle to Prophet Song, publishing successfully and independently does not mean there is only one way to publish

I raise this now not just to encourage “everyone” to start working on their Nibbies entries, but also because it speaks more generally to how we think about this sector, which is not that money should dominate publishing’s decisions, but that the health of the wider ecosystem – within which corporates play a key role – is a good thing.

Alternative funding models for the arts are available but to my mind never look particularly attractive. Close to 200 organisations in theatre receive Arts Council funding in England, compared with just 59 involved in literature (of which just a small number publish books). Theirs is a world with dependency baked in. By contrast, book publishers do pretty well – their routes to consumers have improved over the past decade, while their costs of supply have diminished. Without the strings attached that come with funding applications, they are free to explore this situation as they wish. Grants, when necessary, can be both targeted and beneficial, a boost rather than the crutch.

The author revenue chart in this week’s issue is a good example of (mainly) big publishers getting it right, not just in creating success but providing pathways for other authors and publishers. I daresay Gabrielle Zevin – whose big breakthrough came with her 10th book – is pretty happy with the system at Vintage, as Jamie Smart must be of DFB. From Murdle to Prophet Song, publishing successfully and independently does not mean there is only one way to publish. Neither, for the record, do books just need to be about the words, as the Bunny said to the Monkey.