You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

The creative pact

A couple of weeks ago my youngest child produced a piece of homework with the help of artificial intelligence (AI). By which I mean, of course, that a computer wrote it: I realised this because the language used was slightly above his comprehension level. In other words, it didn’t sound like him. When queried about the unusual sophistication, he reproduced it as if written by a 13-year-old. I don’t wish to out my own child – he had to re-do it anyway – but my point is that the every-day use of AI is already in play, adopted and adapted by the next generation.

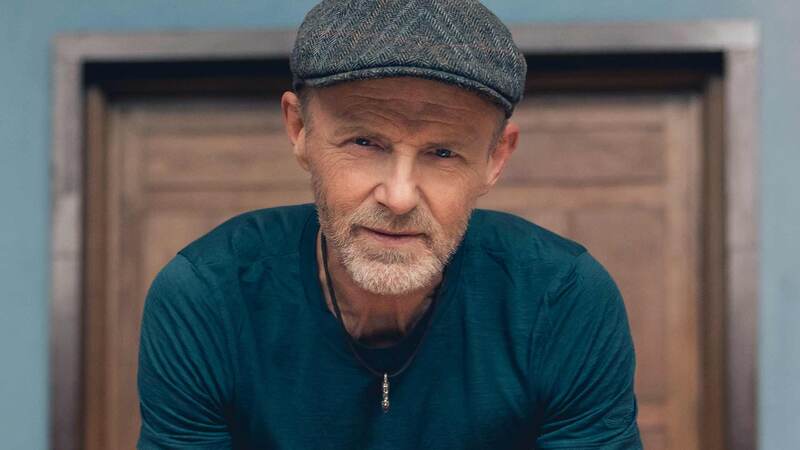

Last week we published online a column “Craft and creativity” written by the AI exponent Nadim Sadek on the subject of assisted creativity. I’ve met Sadek a few times and heard him speak on AI at many industry events. He is thoughtful and occasionally provocative, as was his piece.

Rather like my son’s homework though, when I read it, it made me do a double-take. His thesis was how new technologies may help those with ideas but not ability create something meaningful. AI could be a “means of fashioning an artefact from a creative impulse without having to master the craft of expression”. The argument against this is that AI can only regurgitate from what it has taken (or stolen) from others, lacking the nous to actually fashion something new. Responding, the writer Jamie Fewery argued that computers lack the taste gene creatives rely on. “We should not mistake a thing that creates with one that crafts,” he wrote.

If we wish for AI to help us, rather than replace us, then we need to engage with our eyes open

I think I am somewhere in the middle. The creative act is a precious one – but few ideas survive intact first contact with the page. The process of making is a part of the finished work. Give that to a computer and something else will emerge.

Yet the reality is that AI is already being used to publish books, and it may be that one day a collaboration between human and computer will produce something that some publishers regard as good enough. It is possible this has already happened. Writing professionally is rarely done alone – with most books moulded along the road to publication by those unseen hands in editorial, production and marketing. Just this week a new company, ClioBooks, launched offering to use AI as a “voice-assisted ghostwriter and editor for non-fiction books”, allowing users to speak their words and a computer type them out, or as the company says, assisted planning, recording, and editing. As Sadek suggested, non-fiction may be the area where this first develops, given, as he made clear, the limits on how well computers can actually write. There was a strong reaction to Sadek’s piece, so I reached out to him for further thoughts. Here is what he said:

I think the blizzard of indignant and outraged discussion that has (often with good reason) raged around AI and copyright has caused a certain amount of blindness and deafness to its many benefits. In my column last week, I did not advocate for AI to write books. I never will. Nor did I say that the craft of writing should be considered superfluous and anachronistic. Though I was misconstrued, I take the blame for not properly communicating. My intention was to convey a philanthrophic excitement that the era of AI gives what I believe to be the mute majority of the world to have a means of exploring how to manifest their creativity. I am excited by standing on the threshold of new thinking, new art-forms, new voices in our midst. And in publishing, this should mean a wonderful new volume of freshly enabled writing. Not written by AI, no. Just worked through with allied intelligence, a companion in exploring in thinking and feeling. Using AI to have impossible conversations to iterate a point of view. Using AI to collide previously un-intersected concepts, to create a new perspective on the world. I asked us to be humble in welcoming these new creators in our midst. I expressed delight that staring at a blank page and ‘not being able to write’ would no longer be an impasse to those who don’t know how to craft words together. But, again, not to ‘prompt AI to write a book’.

Personally, I think Sadek is too hard on himself. We are at an inflexion point. Some publishers are making deals with the AI companies, others going to war. That we need to discuss what this future looks like, and what the rules of engagement should be, is clear. AI is not a neutral tool. Our usage of it is to be complicit in how it was made and catalysed. Like the famous Tiger created by children’s writer Judith Kerr, if we let it in, it will likely guzzle more from the table than we might wish. At least that cat left, this one won’t.

We are now presented with another problem. The response to Sadek’s piece online was not benign – or fair. Fewery said he reacted to it with “equal amounts of interest and consternation”, which was a few degrees milder than some of the stuff I’ve seen on social media. I don’t wish to sound trite, but if we wish for AI to help us, rather than replace us, then we need to engage with it with our eyes wide open. We cannot adapt or resist what we do not understand.