You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

The three foot problem

We cannot support creatives on the one hand and undermine them on the other.

A few weeks ago I wrote that Artificial Intelligence may follow other past passing threats to the books business—such as the internet and e-books—in its short-term impacts being wildly overstated, and the longer-term implications largely misunderstood. Since then, as you might expect, the noise around AI has grown as more of us discover ways to use it.

A couple of weeks ago Bradford Literature Festival was criticised for using AI to create an image used for its marketing, while just this week at The Association of American Publishers’ (AAP) annual meeting, c.e.o. Maria Pallante proffered that, although “hugely exciting”, the lack of a road map for AI resulted in uncertainty.

There is a connection here. In response to using an AI-generated image for its brand campaign, a number of illustrators and creatives asked how Bradford could justify using a computer to create new images sourced, most likely, from past images drawn by a human hand without acknowledgement, payment or indeed overseeing (one of the images used appears to have three feet). Author and illustrator Emma Reynolds wrote publicly: “There is currently no ethical way to engage in AI as it scrapes millions of images without people’s consent, which is hours of unpaid labour. It is infringement and it sends a bad message.”

One can apply the same logic to written material generated by ChatGPT (and others): AI is the ultimate magpie.

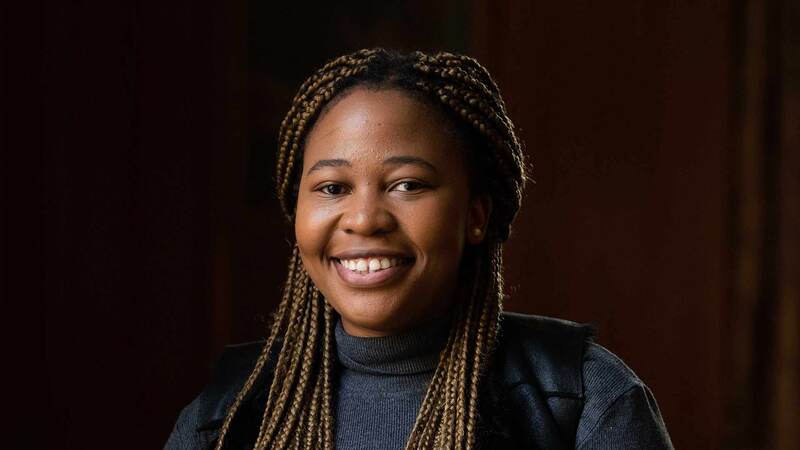

Bradford’s c.e.o. Syima Aslam, in a letter to Nicola Solomon, c.e.o. of the Society of Authors, wrote: “We did not explicitly commission the illustrations or the use of AI, but neither did we explicitly exclude them from our brief”. Fair enough, but requests for the AI-generated images to be replaced on the grounds that, according to Solomon, “AI imagery has mostly been trained on human creative works without permission or reward” have so far gone unanswered by Aslam or her team.

My view is that Bradford was likely taken unawares by the reaction, and its response will surely mean that those of us working in the creative sectors who want to support illustrators and authors will not now use AI-generated images or, if we do, it would need to be intentional. In other words, this “explicitly exclude” language should now become part of a new way of briefing, and this should apply to magazines, event organisers and book publishers. We cannot support creatives on the one hand and undermine them on the other, despite the allure of the new.

The common view of AI is that it just isn’t quite as good as the real thing. That may be so, but there are nevertheless a bunch of areas where it will be useful and we might want to accept that these will shift over time. What doesn’t work today may well work tomorrow. Some advances in technology are actually pretty good: the book being one of them, the e-book another, the internet perhaps one more positive. On Pallante’s undrawn map, Bradford provides a route we need not travel. But we cannot move forwards unless we are also prepared to make a misstep. To err is, after all, human.