You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Actes Sud: the rewards of risk

Chief executive officer of French publisher Actes Sud, Françoise Nyssen, talks to Barbara Casassus about the company's history and its success this year.

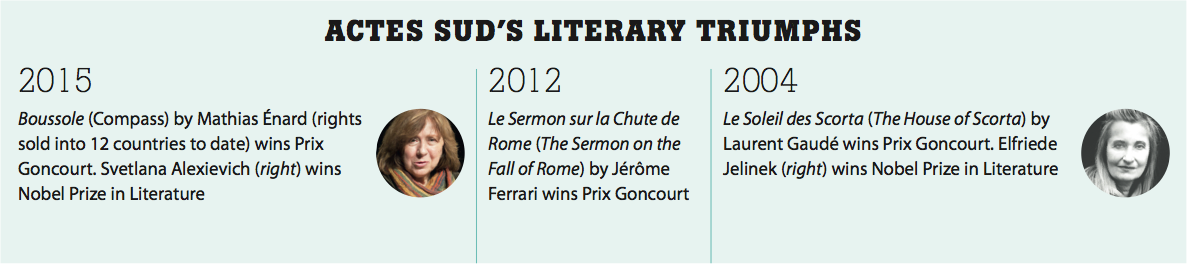

“I am juggling”, declares Françoise Nyssen as she rushes through the Paris office of Actes Sud, searching for space to give an interview to The Bookseller in the aftermath of two major literary triumphs this year: Mathias Énard’s Prix Goncourt for his novel Boussole (Compass) and Belarusian author Svetlana Alexievich’s Nobel Prize in Literature.

Nyssen, chief executive officer of Actes Sud, has no desk in what she considers to be almost an annexe—albeit a growing one—of the publisher’s headquarters in the historic city of Arles in the south of France. But this is just one of several features that distinguishes the company from most of its rivals in France. Françoise Benhamou, economics professor at University of Paris XIII, says it “is the most atypical of all publishers in France. In theory, the house has all the disadvantages—it started from scratch, was founded by people outside publishing and began with translations.”

A key point is that Actes Sud asks only whether a book is good or bad, not whether it is a potential bestseller, adds Benhamou, who specialises in culture and the media. “This entails a great deal of risk.”

The risk has paid off. Enard’s title is the publisher’s third Prix Goncourt, even though Boussole “is not an easy text”, Benhamou says. “The publisher’s success is very surprising, and is an example for all in the business, including young people who are thinking about creating their own house.” Indeed, swimming against the French publishing tide has not hindered Actes Sud: it rose to 12th last year (from 14th in 2013) in

the sales ranking of the top 200 publishers in France, compiled by trade publication Livres Hebdo.

A strong catalogue and several acquisitions (including Éditions du Rouergue at the beginning of 2005 and, notably, Editions Payot & Rivages in 2003) have boosted the publisher’s financial performance. Sales rose by 1.9% last year—from €69.5m to €70.8m (£50m)—and net profits totalled nearly €1.5m. Thanks to the latest developments, the company appears on course to report record results this year.

The company has not wavered from its philosophy of “fierce independence from all points of view”,adoptedwhenitwas founded in a converted sheepfold near Arles in 1978 by Nyssen’s father Hubert, who died in 2011. This independence ranges from ownership of its capital and “ecosystem” to editorial policy and the elongated format of its books.

Nyssen and her husband Jean-Paul Capitani, who is in charge of development, hold 95% of the capital, and friends and colleagues own the remaining 5%. Plans are to keep it that way. Other publishers wishing to expand through acquisition have made overtures, but aware of Actes Sud’s independence, they do not insist. “We know where they are if our circumstances change,” says Nyssen.

She demurs at the mention of the word success, and prefers to think of Actes Sud’s track record as a natural progression derived from signing up talented authors and building a catalogue of quality titles. For that she pays special tribute to editorial director Bertrand Py, who has been at the company from its inception. “We couldn’t have done it without him,” says Nyssen.

Two words underpin editorial policy: pleasure and usefulness. Rather than predefined objectives, the terms simply rose to the surface as the business grew. Bestsellers may not be the top priority, but they include Stieg Larsson’s Millennium Trilogy and David Lagercrantz’s sequel, which Nyssen describes as an excellent text. Other loyal authors include Paul Auster, Nina Berberova, Giulia Enders, Nancy Huston, Alice Ferney and W G Sebald.

Even though the French publishing industry has always been concentrated in Paris—notably around Boulevard St Germain in the city centre—Belgian-born molecular biologist Nyssen has no intention of bringing all the houses, imprints and 300-plus staff under one roof. Working in Arles, where around two-thirds of its staff are located, has advantages that Paris could never offer. “There is a very specific light and the quality of working time is better,” she says. “For a start we have fewer interruptions.” Apart from that, the company runs a bookshop in Arles (one of eight it operates nationally, with a ninth due to open in Paris in December); the city also has the Méjan Association, which stages concerts, art exhibitions and readings; and a three-screen cinema that shows auteur films.

Although clearly elated by the two prizes, Nyssen also notes that the seven non-prize-winning books published by Actes Sud since the summer also deserve recognition and acclaim. “Naturally we are disappointed when talent is not rewarded,” she says.