You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Alma Books: an independent risk worth taking

Twenty years on from launch the indie has grown and reinvented itself, but founders Alessandro Gallenzi and Elisabetta Minervini still have the ‘fire in the belly’.

Twenty years ago, husband and wife team Alessandro Gallenzi and Elisabetta Minervini made a very big wager on themselves, leaving Hesperus Press – the fiction in translation specialist they set up in 2002 with two others – to found their own independent publisher. The duo literally bet the house: seed funding for Alma Books came from remortgaging their home.

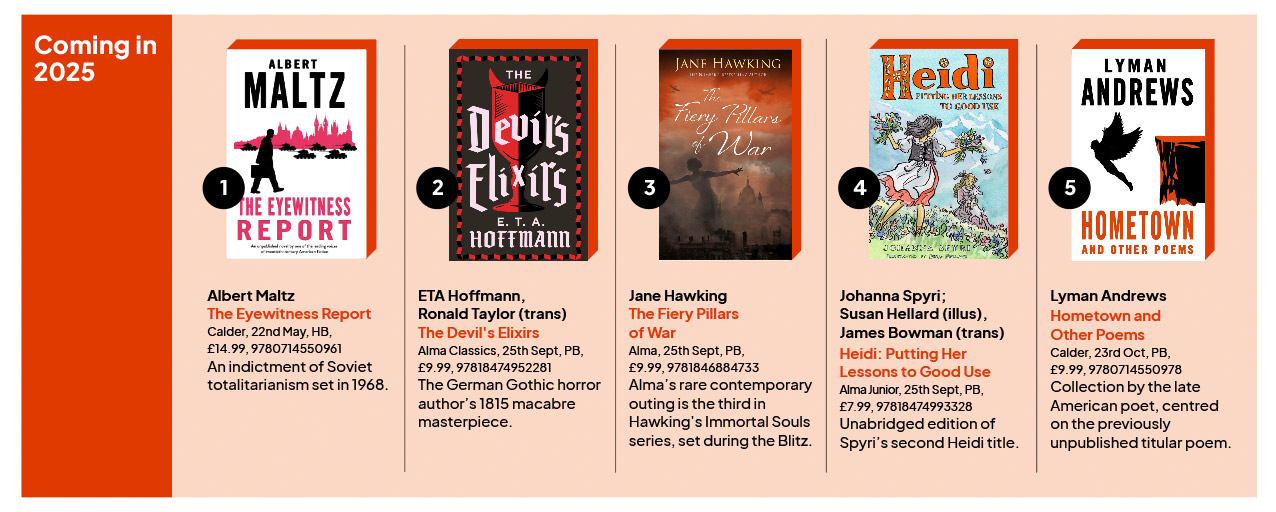

It proved money well spent, as it has been a fruitful two decades for the “small but beautiful” indie, with highlights including publishing a number of award winners and bestsellers such as Tom McCarthy, Rosie Alison and Aharon Appelfeld; the acquisition in 2007 of publishing legend John Calder’s list; bagging an overall UK number one with Jane Hawking’s Travelling to Infinity (Alma is one of just six indies to notch the chart pole position since accurate records began); and, in 2013, claiming the then-British Industry Award (now British Book Award) for Independent Publisher of the Year.

There have been many triumphs but as we sit down ahead of Alma’s 20th anniversary bash at this London Book Fair, Gallenzi and Minervini say that running an indie of their type has necessitated some “concessions” over the years. That includes the size of the publishing programme. “In those early years, we were publishing 80, 90, possibly 100 books a year,” Gallenzi says. “It was too many. Now, we are running at around 40 titles annually, which is the perfect number for us because we’ve always wanted to focus on the quality of what we publish, rather than having a scattergun approach.”

Every year we have a lot of conversations... Is a particular book going to make an impact? Is it important? What can we do if we publish something that also exists in other editions?

But the big shift for Alma was morphing from having at least half the output made up of new, often cutting-edge literary works to a list centred largely on classics and reissued/rediscovered 20th century works, with a few freshly commissioned contemporary titles “just for fun”. This was a gradual change and emerged after fully acquiring the classics imprint it had jointly run with fellow indie Oneworld and rebranding it Alma Classics a dozen years ago, and with the ongoing integration of the huge Calder back catalogue.

Gallenzi says: “When we started off, we had Colson Whitehead, William T Vollmann… it was all very highbrow. One of the things we felt was most aggravating is that we had to make concessions and go more commercial than we would have liked if we wanted to survive. We had successes, like Michel Benoît’s [Da Vinci Code-esque] The Thirteenth Apostle, but thought we were suddenly on a path towards going completely mass market, into commercial women’s fiction –”

“And crime,” Minervini says, picking up the thread. “But it wasn’t really what we were interested in. You cannot be blind to the market and what’s popular. But [those genres] were not something we would have been interested in; there are publishers who can do a better job and are more passionate in those areas. That’s why we thought: ‘Okay, we should do what really interests us.’”

Old school

Classics had been a passion for both of them from the start; even back to the Hesperus days, which had a significant continental European classics tranche. It is a crowded field, of course, from the Penguin behemoth to other indie players like Wordsworth Editions. “Every year we sit down and have lots of conversations,” Gallenzi says. “Is a particular book going to make an impact? Is it important? What can we do if we publish something that also exists in other editions? What can we do editorially that gives it value to make it stand out?”

To succeed, they say, there needs to be brilliant design, rigorous editing and notations. “But not overbearing annotations,” Gallenzi stresses. “Even our edition of James Joyce’s Ulysses, which has 9,000 notes and I think is the best on the market, is done very economically so that it doesn’t override the work. So the way we annotate the titles and curate the text is just as important as the design and the package.”

The Calder side of the list keeps on giving. The late maverick might have been the kind of person Gallenzi had in mind with “scattergun” publishing, but he had exquisite taste: in his nearly 60-year career, Calder hoovered up Nobel laureates, the best of writers across Europe and avant-garde Anglophone authors. It is fair to say that Calder, who died in 2018 aged 91, was not particularly exacting in his admin; with more than 1,500 titles in the backlist, Alma is still unearthing gems.

The big push from the Calder stable this year is Albert Maltz, a popular and prize-winning American author and screenwriter in the 1930s and 1940s – so popular his novel The Cross and the Arrow, about German resistance to the Nazi regime, was distributed for free to US servicemen during the Second World War – whose career came to a crashing halt in the 1950s when he was named as one of the Hollywood Ten, jailed and blacklisted.

Alma has done well with Maltz’s four-strong Calder backlist, but Gallenzi and Minervini discovered, after being put in touch with the author’s grandson, that there were two unpublished novels, which will be released this year. The first, The Eyewitness Report, centres on Czech dissidents standing up to totalitarianism; Man on a Road is a collection of stories dealing with themes of race, gender and capitalist exploitation in America. Both of Maltz’s “new” books resonate in the current political climate, and one can easily see, with his backstory and a following wind, how these titles might inspire an Ulrich A Boschwitz’s The Passenger-esque revival.

Both the Calder list and Alma Classics dovetail with another Alma passion: translation. The duo started their careers as translators when they came to the UK from Italy in the late 1990s. And the Alma Classics list alone has fresh translations of War and Peace, The Brothers Karamazov and Death in Venice in the pipeline for 2025/26.

That is why Alma is funding the new John Calder Translation Prize, which will run with the Society of Authors awards scheme. Minervini says the idea was to salute Calder “who almost single-handedly brought into this country some of the greatest international writers of the second half of the 20th century”.

Inevitably, anniversaries of this type are a chance to look to the future as well as the past. What might an Alma 20 years in the future look like? Minervini laughs: “If we’re still alive? We’ve been talking about how the market has changed over these years, and I think it might move in an interesting way that we want to follow [and if so] we will still want to publish.” Gallenzi adds: “We do talk about [the long term] a lot. Alma in, say, 2045 might depend on what the next generation decides, and we are blessed with two very bright kids who might take over or might take entirely different paths. But we will publish as long as we still have that fire in the belly. And if it’s not us, we hope that what we started will be continued by like-minded people with the same kind of passion.”