Beijing International Book Fair: How China’s authors fare in Britain

Chinese might not be the hottest translation language in the UK, but sci-fi superstar Liu Cixin is on the rise, while danmei is attracting a new generation of fans.

If you were to ask the first 100 publishing professionals you meet during this Beijing International Book Fair who, by far, is the biggest Chinese author in translation in the UK at the moment, it is probable that all 100 may answer incorrectly.

Most, reasonably, might plump for Liu Cixin. After all, he is—following this year’s huge Netflix hit of his The Three-Body Problem, adapted by “Game of Thrones” showrunners D B Weiss and David Benioff—arguably the hottest science-fiction author on the planet right now.

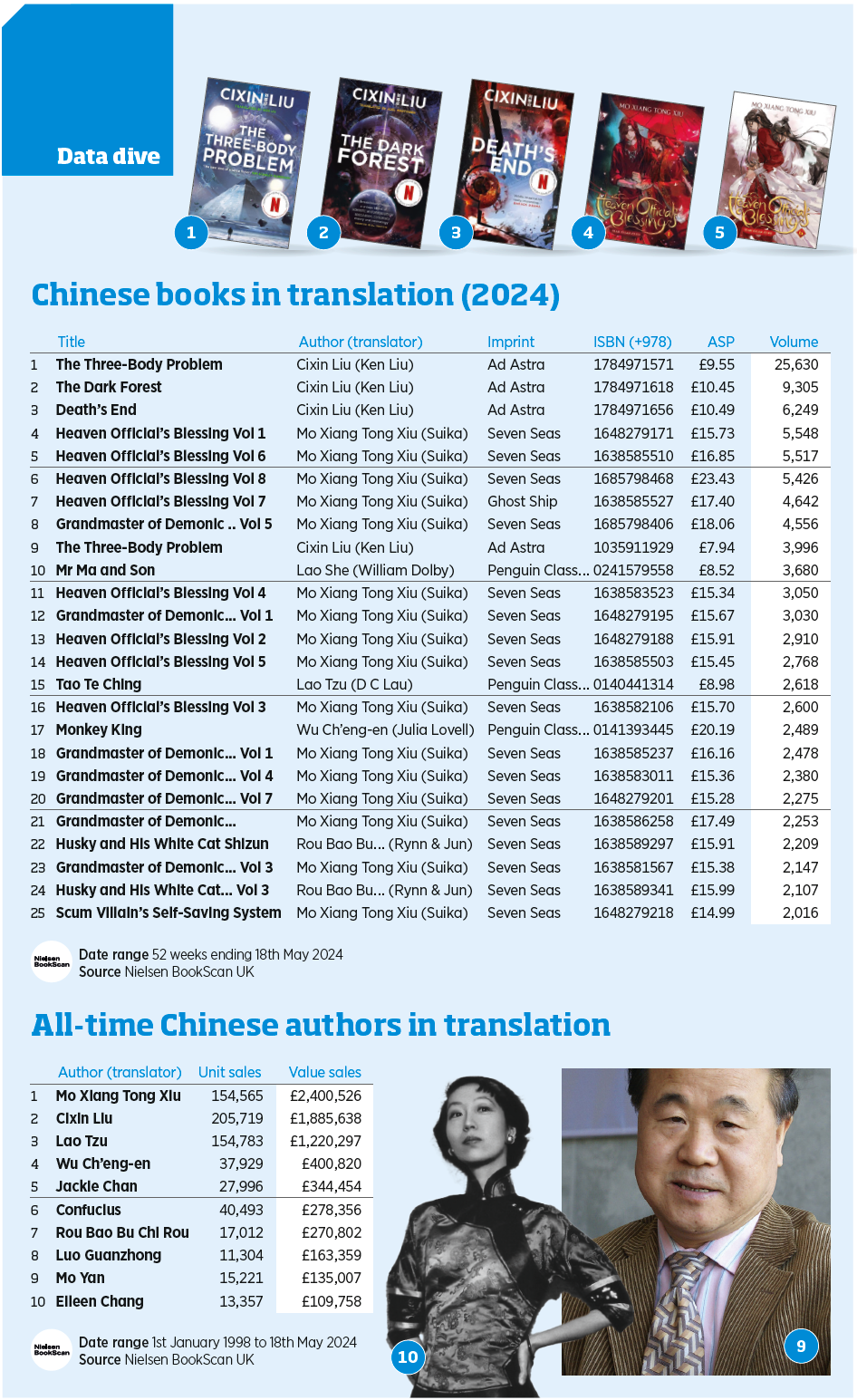

And the Ken Liu (no relation) translation of The Three-Body Problem is, indeed, by a good distance Britain’s bestselling book originally published in Chinese over the past 12 months, with the title shifting almost 26,000 copies through Nielsen BookScan UK’s Total Consumer Market (TCM). A little over half of those sales have come in the 10 weeks since the adaptation dropped on Netflix UK. Two more from Liu’s series are in second and third place, while a tie-in edition of the first book is in ninth place, chipping in a further 4,000 copies.

But while Liu grabs the bestselling title crown, the UK’s top Chinese author in translation is probably little-known outside of a relatively niche audience: the queen of danmei, Mo Xiang Tong Xiu. The author accounts for an astonishing 16 of the top 25 sellers of the past 52 weeks. In that period MXTX (as she is known to her fans in the West) earned £997,000 through the UK TCM, almost double Liu’s total (£499,000).

For the uninitiated, danmei is often heavily illustrated historical fantasy (though not exclusively) novels which focus on romanticised love and attraction between men. The genre has only really been widely available in English in print form since December 2021, when Los Angeles-based Manga specialist Seven Seas launched a danmei imprint, kicking it off with a licensing deal for three MXTX series: Grandmaster of Demonic Cultivation, Heaven Official’s Blessing, and the amazingly named The Scum Villain’s Self-Saving System. The 25 MXTX titles Seven Seas has rolled out since include novels—most translated by the mononymous Sukia, with help by series editor Pengie and accompanied by internal illustrations by ZeldaCW—along with a few manhua (comics) versions.

Since launch, MXTX has become a sensation in the UK, moving £2.4m through the TCM in a little over two and a half years, and in that short space of time she has become Britain’s bestselling Chinese writer in translation since accurate records began.

Manga march

A few things have aided MXTX’s rise: she has undoubtedly benefited from the surge in the UK comics/Manga market and danmei’s fantasy-cum-romance mash-up has made the books a smash on TikTok. Furthermore, Chinese live-action and donghua (animation) TV adaptations of the series are now available in the UK on Netflix and the anime specialist platform Crunchyroll.

Her near-Elena Ferrante level of pseudonymity has perhaps helped build MXTX’s mystique, too. There are no pictures of MXTX online, she seldom gives interviews, and on the rare occasions she updates her social media—like in March this year, when she gave a progress report on her new series—danmei TikTok goes into meltdown, parsing her every character for hidden meaning.

Incidentally, Mo Xiang Tong Xiu is not a name but a phrase, a hard-to-translate concept in English; it roughly means “black fragrance [of ink]”, and “stink of money” and stems from an argument she had with her mother: MXTX wanted to study literature at university, but her parent insisted on economics. So the whiff of the writer’s ink is in one hand, money in the other. Almost all danmei authors are pseudonymous: the moniker of the other UK breakthrough, Rou Bao Bu Chi Rou, translates to “meatbun doesn’t eat meat”. Anglophone fans just call her Meatbun.

Digital to print

Danmei in general is a very modern Chinese publishing story, as the genre thrives on its home turf in the online publishing realm. MXTX, for example, began her career in 2014 on the JJWXC platform, where customers pay a relatively small amount to read each chapter of a story. But seeing this new model transferring to print publishing, and then making significant inroads in Britain, makes it even more striking just how difficult it is for more traditionally published Chinese authors to break through in the UK.

In our list of the top 10 bestselling Chinese authors in Britain since accurate records began, we have Netflix-boosted Liu and our brace of danmei authors, but the rest are mainly a mix of classic novelists and university reading-list philosophers.

Excepting Liu and the danmei duo, Nobel laureate Mo Yan is the only other contemporary author. I’m, undoubtedly snobbishly, excluding Jackie Chan from that equation as the action film superstar’s £344,000 is from his one-off 2018 memoir, Never Grow Up (Simon & Schuster, translated by Jeremy Tiang). That the star of “Rush Hour 3” and “The Tuxedo” has outsold China’s sole Nobel laureate and giant of world letters by a margin of 2.5 to one is perhaps a sad indication of the times we live in.

But it is extremely tough for contemporary Chinese authors to get any traction in Blighty. There was a flurry of UK press around the avant-garde writer Can Xue last October, as she was hotly tipped to win the Nobel (it ended up going to the Norwegian Jon Fosse). A number of Can Xue’s titles have been available in the UK since 2011. Her bestseller? The 2017-published Frontier (translated by Karen Gernant and Chen Zepig), which has sold 198 copies over seven years. Yu Hua is widely regarded as one of China’s greatest living authors and has had 28 titles released in Britain since 1996, but all told they have combined to shift a relatively slim 6,800 units.

True, both Can Xue and Yu are rather high-literary practitioners who produce the type of writing that, even if it were from an Anglophone author, would struggle to find an audience without winning a major prize. But I wasn’t just picking and choosing extreme examples to prove a point; this modest level of sales crosses most genres.

There were a flurry of UK rights deals for Cao Wenxuan’s work after he won the Hans Christian Andersen Award, a.k.a. the “children’s Nobel”, in 2016. Yet these have not really produced much fruit, with sales of 3,200 copies across six books over the past eight years. After visiting BIBF several years ago, I thought the excellent Hong Kong crime writer Chan Ho-Kei would be a hit—a Chinese Stieg Larsson, perhaps, who would unleash a Sino-crime trend in the UK. But his two books published in English, The Borrowed and Second Sister (translated by Jeremy Tiang), have sold just 1,700 copies since 2017. I should underscore I am looking narrowly at UK performance and the low level may just be down to British myopia. Chinese writers fare far better in other Anglophone territories that have greater cultural and ancestral ties with China—the US in particular, of course, but also Australia.

Chinese writers fare far better in other Anglophone territories that have greater cultural and ancestral ties with China—the US in particular

A translated surge

The reasons why there are relatively few Chinese authors breaking into Britain has been chewed over many times in BIBF’s past and will undoubtedly feature in discussions in the halls of the venue this week. But there are reasons to be hopeful for those who want to bring more Chinese literature into Britain. The timing is certainly ripe. The UK—long not the most fecund place for books from abroad—is in the midst of translation boom, which last year accounted for a record 12% of all print fiction sales, up from the circa 3% it had stagnated at for much of the 2010s. So, the market is more receptive than it has ever been to voices from other countries. And China is not that far down the UK translation league table: a Nielsen Books & Consumer survey last year showed Chinese was the 10th-most translated language. Japanese is far and away the biggest language in translation in the UK at the moment, while Korean is surging. And while Chinese-to-English translator Jack Hargreaves astutely says that it is reductive to lump East Asian languages together, it is interesting to note that it was just a little initial spurt which saw books from both territories start cascading into Britain.

For Korea, it was Han Kang and translator Deborah Smith’s The Vegetarian winning the 2016 International Booker Prize—and the book subsequently becoming a hit in bookshops— that had British publishers hunting for the next big Korean thing. (It probably did not hurt that other Korean pop culture—K-pop bands like BTS, Bong Joon-Ho’s Oscar winning film “Parasite” and Netflix’s “Squid Game”—were on the up, too). The Japanese translation market was for a long time very quiet, with Haruki Murakami often the sole representative in British charts. But then it was supercharged by two prongs over the past three years: a massive spike in the Manga market and the “cosy fantasy” boom, led by Toshikazu Kawaguchi’s Before the Coffee Gets Cold series. So, Chinese translation into the UK might just need its “The Vegetarian moment”: that one book or hot trend that piques British publishers’ interest in other authors and works. And, who knows, with Liu’s ascendancy and the danmei success in the past year, maybe that jump-start has already begun.

China’s past and present inspires purple patch of English-language success

While books originally written in Chinese are not yet popping at the tills in Britain, readers are increasingly keen for stories about or inspired by Chinese history and legend—and the Chinese immigrant experience. It’s just that currently these books are being written in English by (mostly) Americans who originally hail from China or are of Chinese descent. Guangzhou-born Rebecca F Kuang is arguably the biggest crossover literary/fantasy star in the Anglophone world right now, selling £5m through the UK TCM over the past two years, driven by her much-lauded contemporary satire Yellowface and Babel, her speculative novel set during an alternate reality Opium Wars. (In May, Yellowface just won the British Book Award for Fiction Book of the Year). Florida native Ana Huang has had a similarly huge splash, with BookTok helping her sell £4m worth of her romance novels in the past 12 months. Huang, whose books often centre around strong Asian-American women, began writing as a child to improve her English as her immigrant parents spoke Chinese at home. And in the fantasy realm there have been a raft of Sinocentric hits in 2024, including A Y Chao’s number-one bestseller Shanghai Immortal (set in idealised Jazz Age China—with vampires), Shelly Parker-Chen’s She Who Became the Sun (which reimagines the life of Zhu Yuanzhang, founder of the Ming Dynasty) and Sun Lynn Tan’s Daughter of the Moon Goddess, which was inspired by Chinese mythology.