You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Chapter and verse: Faber founder’s grandson looks at 90 years of publishing

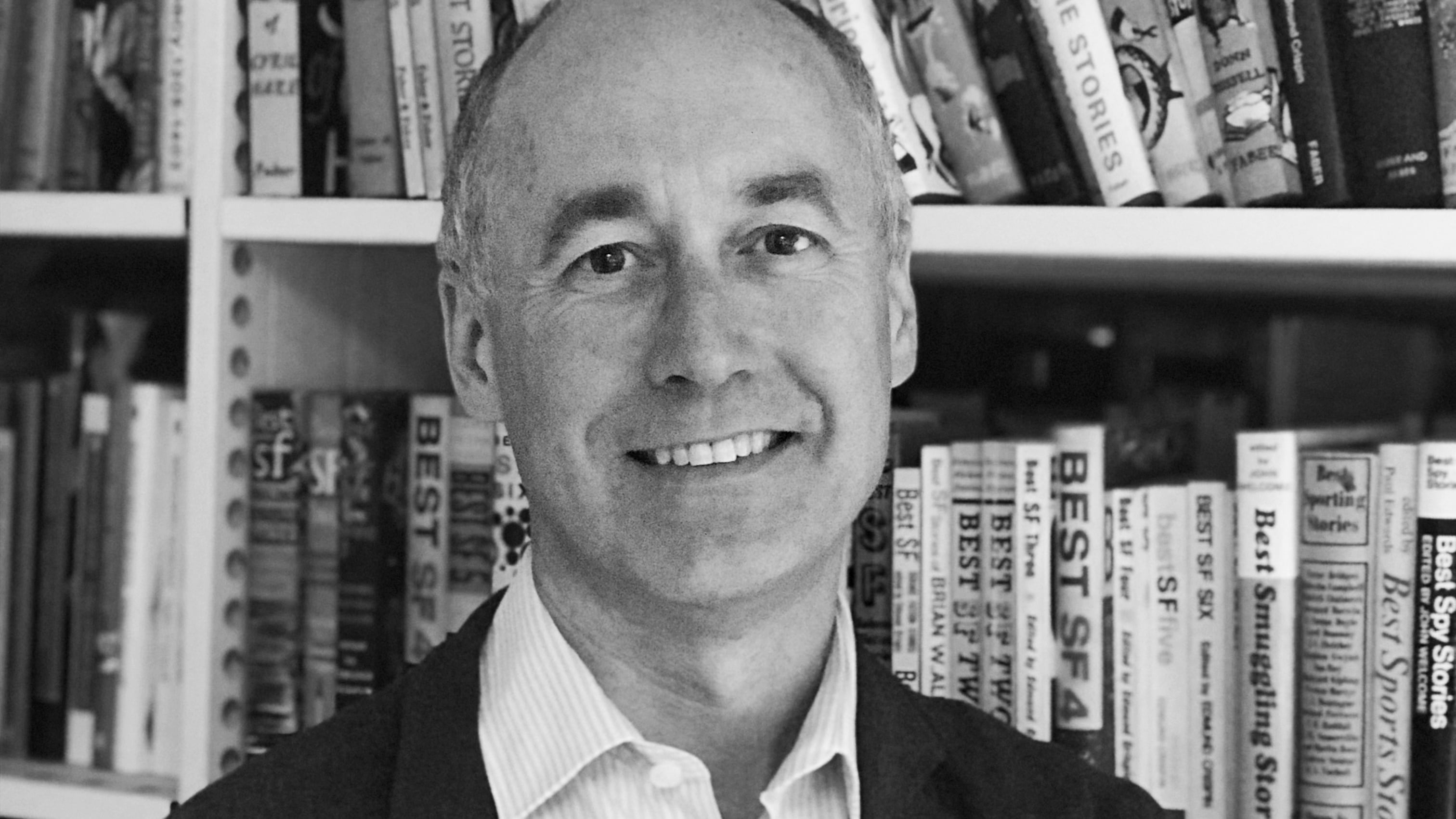

A look behind the scenes of Faber through the 20th century is one of the books marking the publisher’s 90th anniversary this year. Compiled by Toby Faber, grandson of founder Geoffrey Faber, and himself the company’s m.d. between 1997 and 2001, Faber & Faber: The Untold Story of a Great Publishing House trawls the archives for the inside story of the publisher’s development into an illustrious literary house that has succeeded in maintaining its independence.

Faber has had, and continues to have, acquisition offers, Toby Faber says. But a structure put in place in 1990 saw 50% of the publisher go into the ownership of T S Eliot’s widow Valerie Eliot (now her estate); the remaining 50% stayed with the Faber family, making it “virtually impossible” for it to be sold. Neither party is permitted to part with its share without the other’s consent.

Faber’s 90th has fallen well, given the inevitable cycles of literary publishing. The company lost money and was forced to make redundancies in 2015, but has since had a run of strong financial years, scoring coups such as 2018’s Man Booker win for Anna Burns, and a Nobel for Kazuo Ishiguro the year before. The fact that it is a family company is also one of the reasons Faber is so well-suited to literary publishing, Toby Faber believes, since the business is “all about thinking long-term, investing in copyright, hoping the copyrights you are investing in will still be making money until 70 years after the death of the person who created it”.

Faber’s 90th has fallen well, given the inevitable cycles of literary publishing. The company lost money and was forced to make redundancies in 2015, but has since had a run of strong financial years, scoring coups such as 2018’s Man Booker win for Anna Burns, and a Nobel for Kazuo Ishiguro the year before. The fact that it is a family company is also one of the reasons Faber is so well-suited to literary publishing, Toby Faber believes, since the business is “all about thinking long-term, investing in copyright, hoping the copyrights you are investing in will still be making money until 70 years after the death of the person who created it”.

And unlike other family firms, he thinks Faber has done well not to be “a job-creation scheme” for the descendants of the founder; of six siblings, Toby Faber is the only one involved in the business, still on the board of directors.

“A lot of companies struggle if they are carrying the dead weight of lots of people who are only there because they are family members. Publishing is a very specific skill, and there’s no reason to suppose that just because someone is a good publisher themselves, their children should be good publishers. We’ve always been very conscious of that.”

Curiously enough, Faber doesn’t think his distinguished grandfather was actually a great publisher. “I think he was a perfectly good publisher in his era [but] not many of the books we publish now do you go, ‘Ah yes, that was acquired by Geoffrey.’ But he was a great recruiter. He recruited this really good team around him, and when he died, the team was still there.”

The most high-profile of Geoffrey Faber’s colleagues was poet T S Eliot, seen in the book doing his bit as a publisher—reading submissions, writing blurbs—while bringing out works like Ash-Wednesday and The Four Quartets. “He would have been very good at anything he did,” says Faber. “When he talks [in archived letters] about the individuals working for the firm, and their strengths and weaknesses, you can see that if he had chosen to run a company, he would have run it very well. Instead he was the most influential poet of the 20th century...”

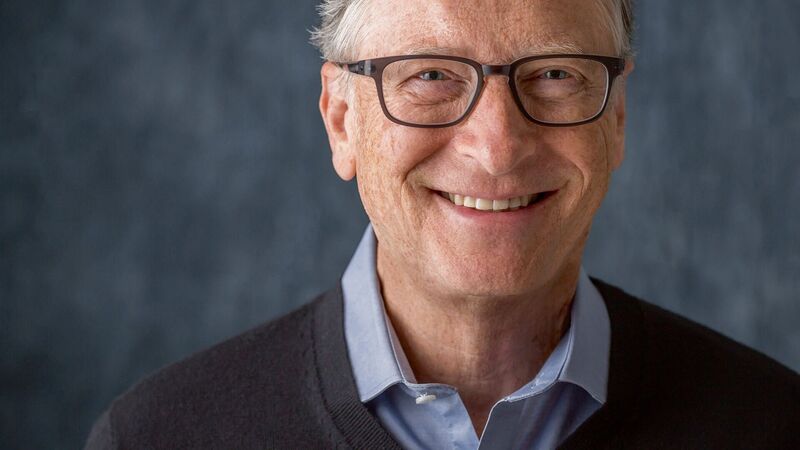

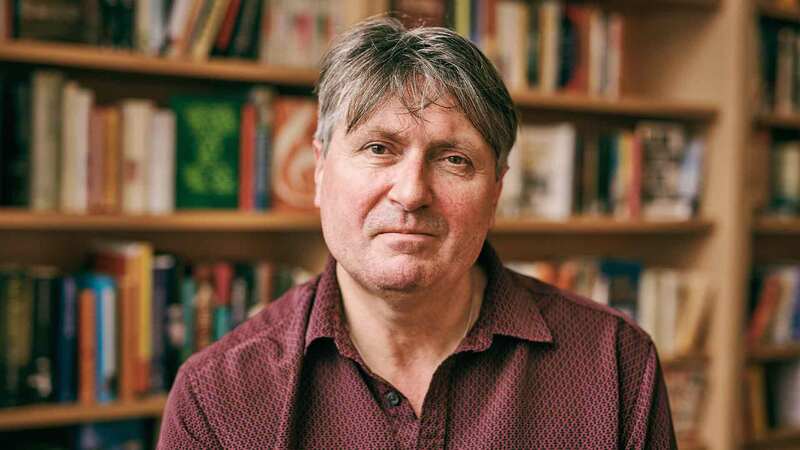

The post-war era saw the arrival of another stellar publisher, Charles Monteith who, in a dynamic wave of commissioning, brought in names such as William Golding, Jan Morris and Thom Gunn. In the ’80s came a further distinct wave under the chairmanship of Matthew Evans, when editorial director Robert McCrum brought Ishiguro, Peter Carey and Mario Vargas Llosa onto the lists.

Word of mouth

There’s much literary gossip in the book: notes to and from Philip Larkin, Ted Hughes, Tom Stoppard, Benjamin Britten; debates over the title of the Golding text that became Lord of the Flies; a letter of apology to a London club where Gunn turned up to a meeting in a (deemed unsuitable) leather jacket. The book also ’fesses up to Faber’s publishing howlers: passing on George Orwell’s Animal Farm; a reader’s report which dismisses Michael Bond’s Paddington: “Unless I mistake him, he means to be funny, but the jokes are all on the bear... Frankly the best of the book lies in its title.” But there are also the prescient judgements: approaches to promising new voices like John Osborne, Sylvia Plath and Seamus Heaney.

There’s much literary gossip in the book: notes to and from Philip Larkin, Ted Hughes, Tom Stoppard, Benjamin Britten; debates over the title of the Golding text that became Lord of the Flies; a letter of apology to a London club where Gunn turned up to a meeting in a (deemed unsuitable) leather jacket. The book also ’fesses up to Faber’s publishing howlers: passing on George Orwell’s Animal Farm; a reader’s report which dismisses Michael Bond’s Paddington: “Unless I mistake him, he means to be funny, but the jokes are all on the bear... Frankly the best of the book lies in its title.” But there are also the prescient judgements: approaches to promising new voices like John Osborne, Sylvia Plath and Seamus Heaney.

Two decisions were crucial to the evolution of the publishing house, thinks Faber. First, the focus on good design, first via designer Berthold Wolpe, later with consultancy Pentagram. Second, the decision to become a proper paperback publisher in the ’80s, fuelled by the influx of royalties from the musical “Cats”, based on Eliot’s Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats. “It’s the paperback list that ‘backlists’... Faber is a classic backlist publisher. Sixty per cent of our sales every year are frontlist, but it’s the 40% backlist that gives you stability and helps you ride out the bad years. We started doing some paperbacks during the 1950s, but even in the ’80s we were still selling [paperback] rights, which just seems daft now. Gradually we convinced ourselves—and authors and agents—that we could sell paperbacks, and we needed the cash from ‘Cats’ to help us to do that.”

Faber acknowledges how male-dominated the company was for decades, both in its staff and its commissioning. “There’s a classic photograph of the Book Committee with all these men in it, and one woman, out of focus and with her back to the room. She’s the secretary, there to take notes. Frankly, even in the 1980s Faber was not publishing its fair share of female authors and did not have its fair share of female editors, and by that time it was a real handicap and a weakness. But you only have to look at the list now, and we are in a much better place, at least in terms of gender diversity, than we were even 10 years ago.”

Of the firm’s 2015 wobble, Toby Faber says it had allowed overheads to creep up, and its publishing wasn’t good enough—“we just didn’t have that good a list, and that’s what Faber depends on”—but prospects are now good. “You need to grow, you can’t just stagnate. Our market share in the UK is still tiny, you can imagine that growing through publishing better books. You need to look overseas as well; certainly the sheer ease of distributing e-books is an opportunity to create overseas markets that wasn’t there before. The more existential problem is the question of what happens if agents and authors feel they should only be selling global rights in their books. We are not seeing any sign of that at the moment. Nobody has yet come up with a better model than having local acquisition driving the local marketing and selling that goes with that. I think by focusing on our strengths as being the best literary publisher in the UK, that’s enough.”

There’s one complication for the future: the six Faber siblings are having their own children, so the next generation will see the shareholder numbers rising substantially. “All of a sudden you can start to see how the next generation will have more of a challenge in maintaining that single family outcome in what they want,” notes Toby Faber. “My siblings all get on, so what we must do is put in place mechanisms that will help sort things out in case there are times when people don’t get on.”

Faber & Faber: The Untold Story of a Great Publishing House (Faber, hardback, £20) is published on 2nd May. Toby Faber’s thriller Close to the Edge will be published by Muswell Press on 7th April (paperback, £10.99)