You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Company spotlight: Atlantic Books

After two decades at Faber & Faber, Will Atkinson was asked to steady the ship at Atlantic Books as its new managing director. He tells Tom Tivnan why he couldn’t resist the offer

It is a dreary winter’s afternoon outside, but the mood in the offices of Atlantic Books is positively sunny.

“You’ve caught me on a very good day,” Will Atkinson smiles. The longtime Faber sales and marketing boss became Atlantic m.d. in October, tasked with changing the fortunes of the struggling indie. Days like today will help: he just received early chart information to learn that two titles—the film tie-in edition of Cheryl Strayed’s Wild and neurosurgeon Allan Ropper’s Reaching Down the Rabbit Hole—have hit the non-fiction bestseller lists.

“You’ve caught me on a very good day,” Will Atkinson smiles. The longtime Faber sales and marketing boss became Atlantic m.d. in October, tasked with changing the fortunes of the struggling indie. Days like today will help: he just received early chart information to learn that two titles—the film tie-in edition of Cheryl Strayed’s Wild and neurosurgeon Allan Ropper’s Reaching Down the Rabbit Hole—have hit the non-fiction bestseller lists.

Additionally, Atlantic chalked up its first Kindle number one in some time, with Thomas Christopher Greene’s The Headmaster’s Wife—sort of a Vermont-based Notes on a Scandal and certainly not erotica, despite the Sylvia Day-esque title—hitting the top spot the previous day. ”And that was at £2.99, not at some bargain price,” Atkinson notes with evident satisfaction.

“There hasn’t been an Atlantic book on a bestseller list in a long time,” he adds. “This is important; it’s about getting back in the game.”

In the past few years, Atlantic has not only been out of the game, but bruised and battered, watching morosely from the stands. Three consecutive years in the red included a whopping £5.1m loss on turnover of £6m in its 2012 accounts. Since 2011 there have been restructures and redundancies, with high-profile departures including Anthony and Nick Cheetham, Ravi Mirchandani and its founder and c.e.o. Toby Mundy.

So why leave the cosy confines of Faber? Atkinson had been at the publisher since 1994, and helped to build the Independent Alliance into a sales and marketing behemoth, in the process becoming one of the industry’s leading faces from the indie sector. Atkinson says: “The reason I came to Atlantic is because I liked and I understood its publishing. I have my own views on what happened. It’s easy to talk ill of the previous regime but it’s not really necessary . . . and kind of pathetic. You have to remember that while Atlantic has not had the most successful three years—that’s what you call an understatement—it has had many very good years.”

There was also a personal challenge. “At Faber, I was getting further away from the books and the writers, and this was a clear opportunity to get super-involved in the publishing and the authors. Leaving Faber was in no way negative, but I was becoming sort of a suit, really.”

Increased stability also appealed. One bright spot of Atlantic’s annus horribilis was that well-respected (and relatively deep-pocketed) Australian indie Allen & Unwin, keen to grow its global reach, assumed 80% control of the company, effectively becoming Atlantic’s owner.

The Long game

The Long game

Atkinson will not radically reinvent what Atlantic does. Instead he thinks the company needs to “return to its heartland”—something epitomised by Reaching Down the Rabbit Hole; a title which combines the middle to high-brow and commerciality. “My brief is to go back to what Atlantic stands for, what it is good at. Some of that is in a very tough marketplace—quality non-fiction is extremely hard to do—therefore it’s about being clear about what we do and what we don’t do.”

There will be tweaks. Atkinson will seek more “big ideas” titles in non-fiction, and he says it is imperative that the publisher “finds a Christmas”. He explains: “Atlantic never really had a Christmas programme, but it’s hard for the indie sector. Profile is a good model—its autumn is not dumbed down or celebrity-driven, but it still feels like Christmas.”

With Atlantic Fiction, Atkinson is happy to play a long game: invest in and nurture authors and not be afraid of the “capital-L” literary titles. He says: “In profit and loss terms Atlantic Fiction may lose money three years out of five, break even one year and make ridiculous amounts of money one year. That washes across the five years.”

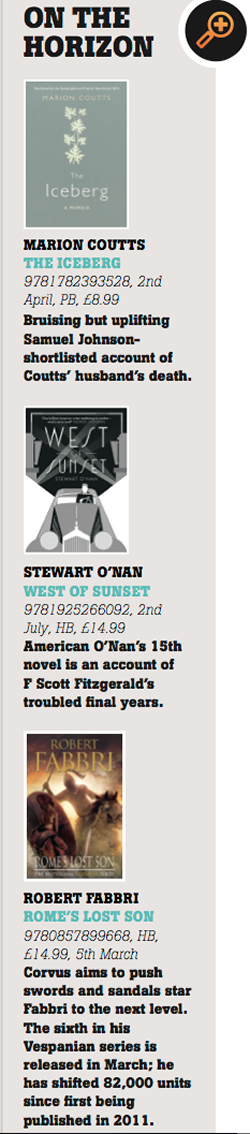

What will enable Atlantic to play the long game will be genre fiction list Corvus “paying a bigger percentage of the bills”. Practically, building Corvus means “attention to e-books, spending money on and building brands”, a situation which actually has been helped by Atlantic’s somewhat profligate past. “In the full-blown galleon days of Anthony Cheetham, guess what—Atlantic bought a lot of books,” says Atkinson. “But they were playing a volume game and my respect for the Cheethams, particularly Nick, has increased considerably since I’ve been here; there is a lot of stuff on the Corvus list that works, especially digitally.”

Take care

If there is an overarching goal for his tenure, it is to make Atlantic more of an author-centric company once again. “I think maybe because of the tough times there has been a hiatus . . . We have people who are close to our authors—[head of publicity and associate publisher] Karen Duffy is a force, for example, as is [publishing director] Margaret Stead—but an independent company has to have writer care as our raison d’être. Every day we have to justify why we are worth 80% of an author’s income, why we are worth more than he or she could get by self-publishing.”

He concedes that the company may need to prove itself after a few years in the doldrums, but argues that Atlantic in 2015 should be an attractive prospect for agent submissions, with its new owners, improved cashflow and desire to make a splash in the market. “We have cash to burn,” he says with something of a chuckle. “I do think Atlantic wouldn’t be a bad punt for many authors, rather than them getting lost in, say, the Penguin Random House sales and marketing machine.”

The bottom line is rising. The £5m hole in Atlantic’s 2012 figures was down to a number of one-off costs; the “real loss” was around £2.3m. The company’s 2013 loss was £1.4m, and the 2014 results should be £1m better. Atlantic has been at or bettered budget each month Atkinson has been in charge, and he thinks it will be in the black in 2015.

Again, Atkinson talks long term. “Independence is funny. I was getting to a point, thinking about Quercus or Constable & Robinson, that it was becoming another word for ‘temporary’. Paradoxically, being an indie also gives you time. You don’t have shareholders looking for market rate profit. Our shareholders are looking for us to publish good books, invest in good authors, make a bit of money and have some fun.”