You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Chingonyi credits teachers for his interest in poetry

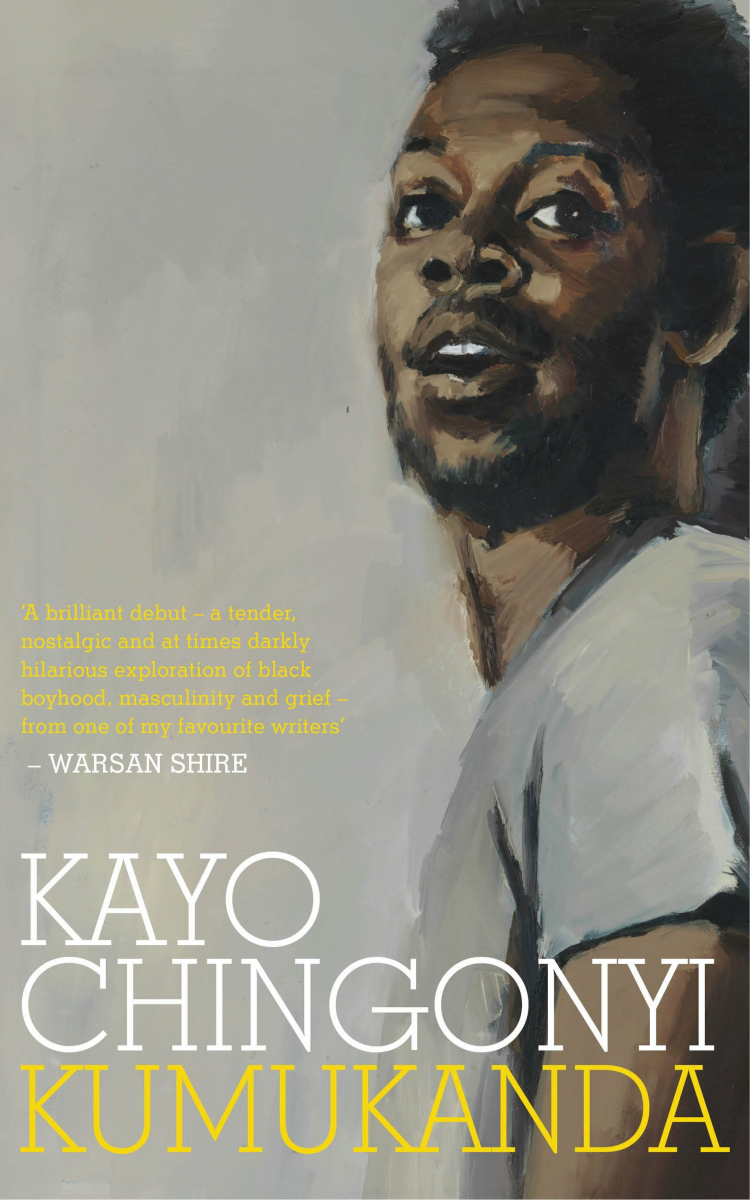

Zambian-born poet and music producer Kayo Chingonyi's debut collection Kumukanda (Chatto & Windus) is an important and assured exploration of the rites of passage boys go through to become men (Kumukanda means "initiation").

Chingonyi was awarded the Geoffrey Dearmer Prize in 2017, and now joins Carmen Maria-Machado, Sally Rooney and Gabriel Tallent on the Swansea University International Dylan Thomas Prize shortlist.

How does it feel to be shortlisted for the Swansea University International Dylan Thomas Prize?

How does it feel to be shortlisted for the Swansea University International Dylan Thomas Prize?

It feels gratifying to be in such illustrious company, especially in a year of such riches for the judges to choose from. Seeing Kumukanda on that list brought a smile to my face. I was staggered when Chatto & Windus bought the book and humbled to hold it in my hands. To see the book travelling and making the kind of impression it has made is more than I could have imagined.

What inspired Kumukanda, your first full-length collection?

The book has to do with initiations of various kinds. Moments of self-identification in which a person’s sense of self is clarified. It is a book that tries to bring together the different things that have influenced me (House Music, UKG, 20th Century British and American Lyric Poetry, Hip Hop, Pirate Radio, my aunt and uncle’s stories, cassette tapes...). The book is an affirmation of the possibilities of a hybrid, global, sensibility.

What are the key themes you explore?

Grief, healing, transitions, the impact and dissemination of culture.

How does the relationship between masculinity and race inform your work?

Both those categories are imposed from without. Living with those labels can, as Denise Riley has it in The Words of Selves, be "brightened by an irony". Some of the work in Kumukanda is playful with racial and gender classifications in a way that is generative to me as someone who is often [mis]read in a particular way because of the tropes that exist in the imagination of some of the people I interact with. The assumptions I interact with are part of what some of the work in the book addresses, particularly in the sequence "calling a spade a spade".

Who or what are your main inspirations and influences?

The word "song" recurs several times in the book (I had to cut a couple of instances from the manuscript, actually, for fear of labouring the point). I am moved by auditory sensation and so it is a big part of the process by which my poems are made and the shape they take. The musical structures in language, then, could be called my main inspiration. The work is also shaped by the work of musicians, writers, scholars, and artists whom I admire. That list is a long one but Dorothea Smartt started me on the path I’m on as a poet by coming in to my school to work with me on my writing. That was in 2003, I think. Special thanks have to go to all my teachers, too. I was very lucky in having engaged and supportive teachers at every stage of my education.

What impact do you hope the book will have on its readers?

I hope the book helps some people feel seen, such that they can go out into the world with renewed pride and courage.

How important do you think live performance is in poetry? Do you prefer your poems to be heard or read?

How important do you think live performance is in poetry? Do you prefer your poems to be heard or read?

I don’t have a preference. I think when a poem is read aloud in a manner that comes from its particular shape then something special happens. If people are engaging with my work, in whatever form, that is enough for me. In writing the work I try to find a balance between words on the page and words in the air but I don’t insist on one mode of reception for my work or indeed for the work of others.

You also work as a music producer – how would you define the relationship between music and poetry? Do you approach them separately or do they inform/complement one another?

I write and record songs occasionally because the process of making music brings me joy. Writing poetry brings me joy too but it is also a part of my working life in a way that music is not. I think it’s important to have some pursuits that are not work. In that sense writing songs helps me to keep the playfulness in my poetry. I try and use the improvisational energy I use when writing songs when I write poems.

Do you think public perception of poetry has changed/evolved in recent years? For example, with the rising popularity of "Insta-poets" such as Rupi Kaur and Nikita Gil?

I don’t know. Poets who enter the wider consciousness in that manner do perhaps open up a space for other styles of poetry, but I also think the work that practitioners, publishers, editors, and promoters have been putting in for a long time is also a part of it. If there were no poetic communities for people to enter once their curiosity had been piqued then we wouldn’t have the levels of activity around poetry that we currently have.

Are you working on anything new at the moment?

I am working on a new book of poems and a prose book of hybrid form about which more will be revealed in the fullness of time.

What was your favourite book of 2017?

Stranger, Baby (Faber) by Emily Berry. Also I loved Will Harris’s pamphlet All This Is Implied (HappenStance).

You can read about the full shortlist here.