You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Edward Platt discusses his travels through flooded Britain

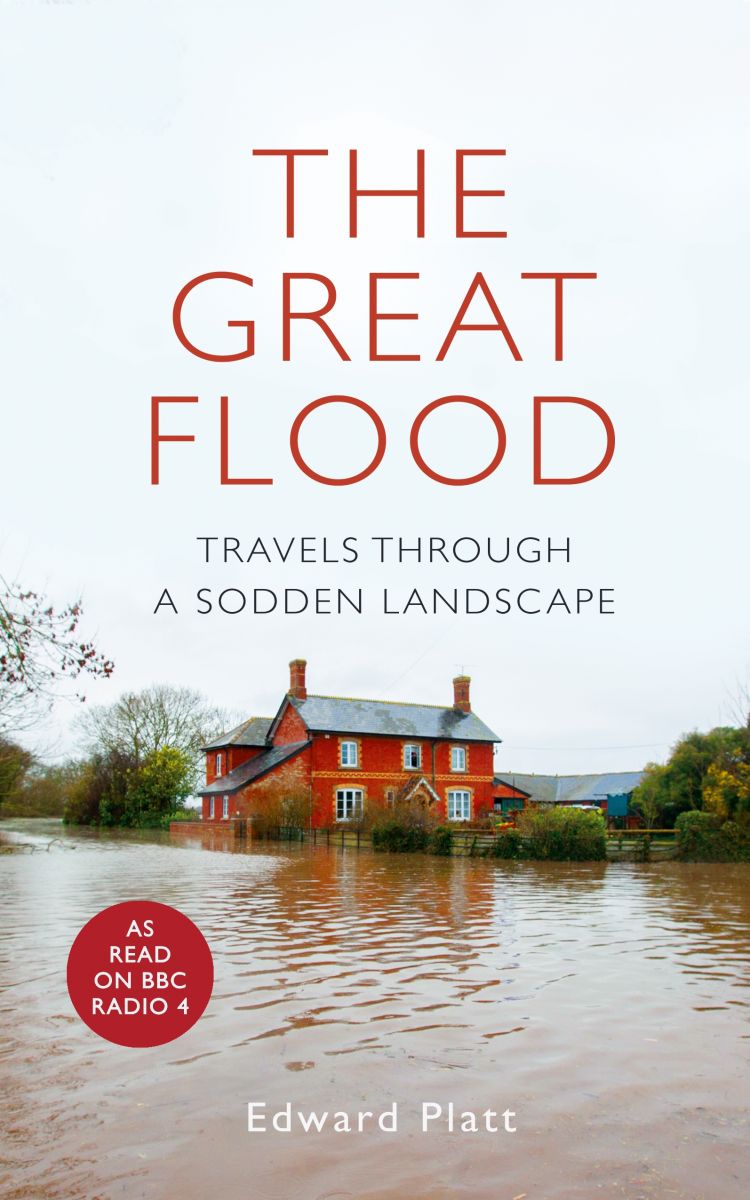

Inspired by complacent attitutes towards global heating, Edward Platt’s latest book interweaves stories of those across the UK affected by flooding.

Award-winning writer Edward Platt began gathering material for his latest book back in November 2012, with a visit to the market town of Tewkesbury in Gloucestershire. Over the following 18 months he travelled across Britain, from the south coast to the Lake District, meeting numerous people whose homes had been affected by flooding, and he tells their stories in The Great Flood (publishing in paperback with Picador in May).

Platt’s inspiration for the book was the increasing number of instances of flooding happening nationwide. He explains: “It was the first manifestation of the climate crisis to affect Britain. Flooding had become impossible to ignore. I thought it was important to understand what it feels like to be flooded—because it is something that many more people will have to go through as climate change takes effect.” The book’s title refers to stories of an ancient flood found across various cultures. In the text, Platt refers to several historic floods and flood myths alongside the more recent accounts of flooding. He says of his decision to explore these in the book: “To most of those affected, being flooded feels like the end of the world, but I wondered if the rest of us seemed so happy to dismiss it because of the inherited knowledge preserved in the stories—that the planet has always flooded, and we have always come through OK. I think there is, simultaneously, a deep and deceptive familiarity with floods and a profound fear of them.

The Great Flood, which took about three years to write, begins in Thorney, a village on the Somerset Levels that Platt first visited in January 2014 when it was under four feet of water. He realised this would provide the book’s opening after an encounter with a friendly local man who gave him a lift through the village in a canoe. “I wanted to start it there, when I was sitting in the canoe, in the dusk, surrounded by the flooded houses, because it seemed a glimpse of the future.” Thorney felt significant for another reason too, as Platt highlights in the book—“Westminster used to be called Thorney, and since so many people in the Somerset Levels blamed central government for what had happened to them, I thought of the two Thorneys as twin towns of a kind, entirely different, yet tied together by the unequal relationship between centre and margin.”

Forgotten flooded

The feeling of being forgotten is prevalent throughout the book. Some of the people Platt encounters have dealt with multiple floodings and years of fallout, from the loss of family heirlooms to relationships breaking down, often with little support from officials. However, as seen in the book, there is no universal response to the experience. Platt explains: “I was fascinated by the way different people reacted to being flooded, and the way they talked about it afterwards. I was particularly fascinated by the people who shrugged off being flooded as a minor inconvenience—not the usual reaction.” He adds: “I wasn’t particularly surprised to meet people who refused to accept climate change as a factor in the floods of 2014—but I still found it disturbing.”

When Platt began writing the book, society was (in his words) “remarkably complacent” about the threat that climate change posed. This provided another impetus for the project. He says: “I wanted to try and understand why we were not more engaged by the climate crisis. I wanted to think about why we find it so easy to ignore.” Now, he attributes this to the obvious—“no-one wants to change the way they live, and they don’t think it will make any difference if they did”—but he also floats the idea of “an inherited familiarity with the planet’s changing moods, articulated through the flood myths, that made it easier for people to discount the threat”. Whatever the reason, it’s clear that half a decade on “the mood has changed”.

Climate challenges

Since the book was released in hardback in October, Platt has been invited to write articles for several media outlets and to speak at literary festivals about flooding and climate change. He is doubtful that mainstream politicians will “rise to the challenge” posed by the climate crisis, but is hopeful that they will be “swept along by popular protests... and by commercial logic.” Either way, Platt believes the growing focus on these issues will have an impact on the travel industry. “Seven billion people exert pressure on the planet in countless different ways, and moderating its effects will not be easy. Many things will have to change—but travel will be one of them.”

Photography: Johann Perry