You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

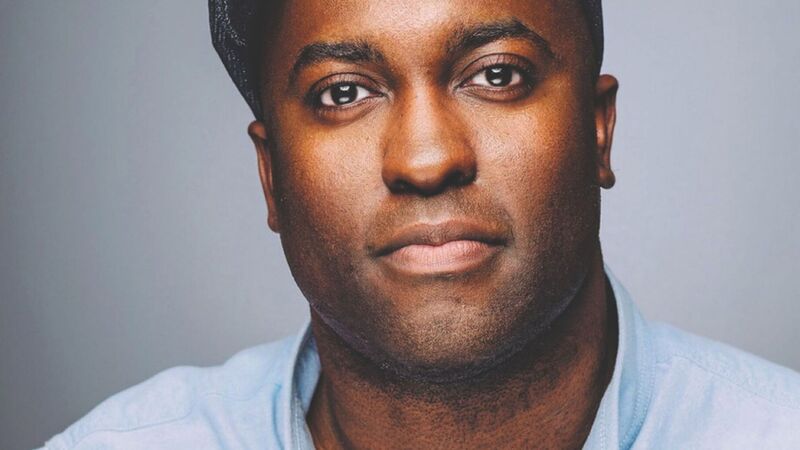

Acevedo ‘thrilled and overwhelmed’ by Carnegie win

Elizabeth Acevedo has become the first author of colour to win the CILIP Carnegie Medal in the prize’s 83-year history, winning the award with her verse novel about a young girl growing up in Harlem.

Acevedo, a Dominican-American writer resident in Washington DC, told The Bookseller she was “thrilled and overwhelmed” that The Poet X (Egmont) won the award, which was announced earlier this week at a ceremony at the British Library. “It didn’t really hit me until I landed at customs and the border agent asked me what I was here for. I had to say I was here for something very important!”

The story is about an American teenage girl of Dominican heritage called Xiomara, who during the course of the book has to deal with her parents’ opposition to her having contact with the opposite sex, while becoming aware of her own sexuality. At the same time Xiomara joins a slam poetry club in school and finds an outlet for the poems she has been writing in a private notebook.

Acevedo began writing the book in 2012 when she was a literature and creative writing teacher at a school where 78% of the pupils were of Latino heritage, and 20% were black. Acevedo was trying to encourage one particular girl to read more, and when she asked why the pupil wasn’t reading, the response she got was: “These books aren’t about us.”

“I realised it wasn’t that these kids weren’t capable but they felt like books were for other people,” she said. “That saddened me so I went to buy lots of other books, which she was into, but then I thought, ‘What about me? Why couldn’t I write something? What have I learnt and internalised that makes me think I can’t do it?’”

The story isn’t autobiographical, although Acevedo said some of the emotional truth resonates with her own upbringing, especially in terms of dealing with the attention she received as a young woman. Yet the decision to write about teenage girls and sexuality was very much a conscious one. “[Xiomara] wants to be invisible but is so seen. I wanted to think about what kinds of permission we give young women about desire. It’s OK to feel desire, to have questions, but also to push back if someone doesn’t respect you.”

The story isn’t autobiographical, although Acevedo said some of the emotional truth resonates with her own upbringing, especially in terms of dealing with the attention she received as a young woman. Yet the decision to write about teenage girls and sexuality was very much a conscious one. “[Xiomara] wants to be invisible but is so seen. I wanted to think about what kinds of permission we give young women about desire. It’s OK to feel desire, to have questions, but also to push back if someone doesn’t respect you.”

In the past, the thoughts and emotions of young women were often seen as “inconsequential” in literature, she said, but the writer is heartened by the fact that publishers are increasingly giving spaces to voices who explore teenagers’ concerns and questions. “When we see this in a book, we realise we are not alone in not liking the way we look, or wondering why someone didn’t call me. I wish I had read more of these kinds of books growing up.”

Acevedo is a slam poet as well as a novelist, although she said there is a big difference between composing poems and writing novels. With her novels she is always thinking about balancing the narrative and plot with the elevation of language, while with a poem the language always comes first. She said The Poet X is a novel in verse, not a “novel in poems”, and the fact that people enjoy performing the novel out loud was a surprise, albeit a happy one.

A runaway hit

The success of the novel has gone beyond anything she could have imagined, Acevedo said. She has won several awards, including The Printz Award for Best Young Adult Novel of 2018, but for Acevedo the best reward is the number of messages from readers who have been touched by the novel. “I’ve had messages from 14-year-olds to 40-year-olds, from women, men, transgender folk, people who felt they couldn’t speak up but say the book made them feel brave,” she said.

Boys, too, have responded well to the book, and many said it let them explore how they interacted with girls and they asked themselves questions like, “why is it not appropriate to pull a girl’s bra strap?”

Aspiring poets have also been inspired to pick up a pen. “Many people were inspired to write poems after reading my book, some of whom hadn’t written anything for several years,” said Acevedo. “It opens up something in people regardless of what I thought the reach of the book would be. Poetry is universal.”

She praised the increase in the number of verse novels being published for young people, too. “They engage readers quickly and drop them into a voice. It is nice to sit inside someone’s head.”