In the early fifties of the last century, a ferocious heat wave assaulted Europe. It choked its way north from Sicily, where it scorched half the island to brownish rust, up toward Malmö at the lowest tip of Sweden; but it burned most savagely over the city of Paris. Hot steam hissed from the wet rings left by wine glasses on the steel tables of outdoor cafés. In the sky just overhead, a blast furnace exhaled searing gusts, or else a fiery geyser, loosed from the sun’s core, hurled down boiling lava on roofs and pavements. People made this comparison and that — sometimes it was the furnace, sometimes the geyser, and now and then the terrible heat was said to be a general malignancy, a remnant of the recent war, as if the continent itself had been turned into a region of hell.

At that time there were foreigners all over Paris, suffering together with the native population, wiping the trickling sweat from their col- larbones, complaining equally of feeling suffocated; but otherwise they had nothing in common with the Parisians or, for that matter, with one another. These strangers fell into two parties — one vigorous, ambitious, cheerful, and given to drink, the other pale, quarrelsome, forlorn: a squad of volatile maundering ghosts.

The first was looking to summon the past: it was a kind of self-intoxicated theater. They were mostly young Americans in their twenties and thirties who called themselves “expatriates,” though they were little more than literary tourists on a long visit, besotted with legends of Hemingway and Gertrude Stein. They gathered in the cafés to gossip and slander and savor the old tales of the lost generation, and to scorn what they had left behind.

They rotated lovers of either sex and played at existentialism and founded avant-garde journals in which they published one another and bragged of having sighted Sartre at the Deux Magots, and were proudly, relentlessly, unremittingly conscious of their youth. Unlike that earlier band of expatriates, who had grown up and gone home, these intended to stay young in Paris forever. They made up a little city of shining white foreheads; but their teeth were stained from too much whiskey and wine, and too many powerful French cigarettes. They spoke only American. Their French was bad.

The other foreign contingent — the ghosts — were polyglot. They chattered in dozens of languages. Out of their mouths spilled all the cadences of Europe. Unlike the Americans, they shunned the past, and were free of any taint of nostalgia or folklore or idyllic renewal. They were Europeans whom Europe had set upon; they wore Europe’s tattoo. You could not say of them, as you surely would of the Americans, that they were a postwar wave. They were not postwar. Though they had washed up in Paris, the war was still in them. They were the displaced, the temporary and the temporizing. Paris was a way station; they were in Paris only to depart from Paris, as soon as they knew who would have them. Paris was a city to wait in. It was a city to get away from.

Beatrice Nightingale belonged to neither party. She had been “Miss Nightingale”—in public—for twenty-four years, even during her marriage and certainly after the divorce, and had sometimes begun to think of herself by that name, if only to avoid the accusatory inward buzz of Bea. To Bea or not to Bea: she was one of that ludicrously recognizable breed of middle-aged teachers who save up for a longed-for summer vacation in the more romantic capitals of Europe. That these capitals, after the war, were scarred and exhausted, drained of all their well-advertised enchantments, did not escape her. She was resilient, intelligent, not inexperienced (marriage itself had taught her a thing or two). She was, after all, forty-eight years old, graying only a little, and tough with her students, high school boys sporting duck-tail haircuts who laughed at Wordsworth and ridiculed Keats: when they came to “Ode to a Nightingale” they went out of their way to hoot and leer — but she knew how to tame them. She was good at her job and not ashamed of it. And after two decades at it, she was not yet burned out.

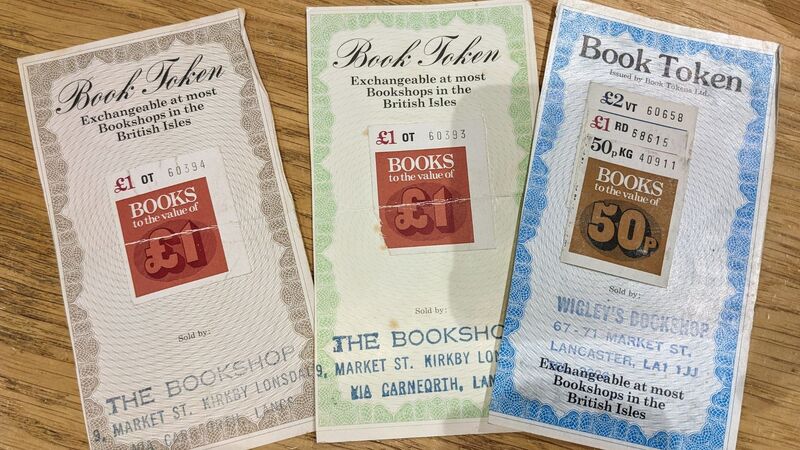

She had signed up for London, Paris, and Rome, but gave up on Rome (even though it was included in the agent’s package deal) when she read, in her noisy hot hotel room off Piccadilly, of the dangerous temperatures in the south. London had been nearly bearable, if you kept to the shade, but Paris was hideous, and Rome was bound to be an inferno. “That ludicrously recognizable breed”—these were her mocking words to herself (traveling alone, she had no one else to say them to), though likely parroted from some jaunty guidebook, the kind that makes light of its own constituents. A more conscientious guidebook, the one sequestered at the bottom of her capacious bag—passport, notepad, camera, tissues, aspirin, and so on—was not jaunty. It was punishingly painstaking, and if you were obedient to its almost sacerdotal cartography, you would come away exalted by pictures and sculptures and historic public squares redolent of ancient beheadings.

On this July day the page she was consulting in her guidebook was bare of Monets and Gauguins and day-trip chateaus. It was cap- tioned “Neighborhood Cafés.” All afternoon she had been walking from café to café, searching for her nephew. A filmy smear greased her vision — it was as if her corneas were melting — and her heart- beat either ran too fast or else meant to run out altogether, with small reminding jabs. The pavements, the walls of buildings, blew out torrid vibrations. Paris was sub-Saharan, she was being cooked in a great equatorial vat. She fell into a wicker chair at a burning round table and ordered cold juice, and sat panting, only half recovered, with her blurry eye on the garçon who brought it. Her nephew was a waiter in one of these sidewalk establishments, this much she knew.

Foreign Bodies is published by Atlantic.