You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Francis Gurry: director-general of WIPO on the challenges of action on copyright

We are in a situation where I think it is very difficult to make international rules, but there is a need for international rules—that is the paradox.” So says Francis Gurry, director-general of the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO), speaking to The Bookseller at the House of Commons on a recent visit to London under the auspices of the Authors’ Licensing and Collecting Society (ALCS) and the International Authors’ Forum.

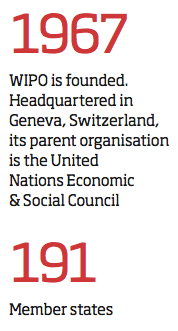

WIPO is a United Nations agency which describes itself as the global forum for Intellectual Property (IP) policy and co-operation; it has just over 190 member states and a stated mission “to lead the development of a balanced and effective international Intellectual Property system that enables innovation and creativity for the benefit of all.” Its concern is not with individual countries’ arrangements on copyright, but on international agreements that all member states can sign up to; it administers 26 multilateral treaties.

And IP is currently right at the top of the international agenda, Gurry says. Western economies are putting it at the centre of their economic strategies because of the huge innovations in science and technology, while there’s a renewed awareness of the contribution made by the creative industries, both to employment and GDP, but also to “soft power” in international relations.

But while the creative industries are being transformed by digital technology, adjusting the legal framework to reflect this is slow work, says Gurry—“we are not trying to do it slowly, but it is happening slowly because it is complex”—and the international climate is difficult. “We live in a world where the international community is incapable of agreeing on the time of day,” the director- general laments. “There are lots of reasons for that, including that the current administration in the US would prefer to do things other than multilaterally—in other words, bilaterally, through individual agreements with countries. It’s difficult, because it’s a deeply divided world in which to move issues forward.”

In effect, it is often the big players who end up dictating the international agenda by default. For example, the newly passed European Copyright Directive, with which WIPO was not involved because it was not on the multilateral agenda, “is going to be very influential”, Gurry predicts.

“That’s the interesting thing: to some extent I think what we are seeing in the world is regulatory competition—competition when it comes to regulatory regimes. For example, General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), protecting personal data in Europe: because Europe is such a big market, it effectively becomes the law for the world, because everyone wants to be in the European market. So then you have to comply; effectively, everyone complies. In the absence of an international rule—and there is no international rule about personal data—certain players that have the scale (Europe, the US, China) are able, by being the first mover, to make the international rule. So now, this Copyright Directive, to what extent will that create an international rule de facto? It’s not a legal rule internationally, but will it create a best practice that others will follow?”

But the multilateral approach of a UN organisation such as WIPO is essential, he thinks, or the regulatory competition between big players with starkly different approaches—e.g., the US and China—can get out of hand. WIPO’s approach, given these problems, is to focus on very specific topics. “It’s easier to do a treaty, or create an international rule, on mercury levels in the ocean than it is on climate change. ‘Climate change’ is too big.

But the multilateral approach of a UN organisation such as WIPO is essential, he thinks, or the regulatory competition between big players with starkly different approaches—e.g., the US and China—can get out of hand. WIPO’s approach, given these problems, is to focus on very specific topics. “It’s easier to do a treaty, or create an international rule, on mercury levels in the ocean than it is on climate change. ‘Climate change’ is too big.

If you drill down to mercury in the ocean, then people might be able to agree—so by being specific and technical, you’ve got a chance. That’s what we try to do with copyright.”

The recent WIPO Marrakesh Treaty, on improving access to books for blind and visually impaired consumers, was one such example: “That’s a specific problem for which there is a very specific solution.” Currently WIPO is also at work on other specific initiatives: on artists’ resale rights, and a broadcasting treaty.

Safety in numbers

Tantalisingly for authors, Gurry holds out the prospect that the Public Lending Right (PLR), which is in operation across 35 countries, could become a WIPO focus, with an extension across its entire membership, boosting PLR status and bringing hard- pressed authors much-needed income from overseas loans. “PLR is a very interesting experience and a very positive experience for the countries that have adopted it, so I would be very interested in seeing that become an agenda item for WIPO. Because, look, we are living in a world where we have to be careful to ensure that artists and authors and composers have a decent economic existence. The overwhelming size of the internet platforms—Google, YouTube, Amazon—is affecting the value chain of creation. In a world of great technological change, which is affecting the business organisation of the creative industries, we can’t let that affect the human beings that created the work.”

But if PLR is to become a WIPO issue, there needs to be an international movement, Gurry explains. “That’s what happened with the Marrakesh Treaty, for example. The blind said: ‘Buster, that’s enough. We’re going to fix this situation.’ So they effectively organised themselves into an efficient group that lobbied governments, nationally and internationally, to change the situation. If PLR is going to happen, that’s what you have to do: you have to build an international movement.”

“And then we look for national champions, a government among our members that is prepared to make a little bit of effort and spend some energy on saying: ‘Hey, you know what, this is a good thing for authors worldwide and it would be good to address this worldwide.’ So you need government champions first, but you also need an effective non-governmental organisation movement.”

Publishers are currently focused on WIPO’s draft Action Plan on Limitations & Exceptions to Copyright, with a major conference set to take place in Geneva this autumn, directly after the Frankfurt Book Fair. Some WIPO members from the developing world are arguing for educational materials to be made copyright- free. The opposing view has been made by Will Bowes of the UK Publishers Association, who wrote on the International Publishers Association’s blog: “Those seeking to exclude education from copyright need to ask the following question. When the world has finished reading, for free, all of the books and journals that exist today, who will pay for the production, curation and dissemination of the books and journals of tomorrow?”

Gurry treads a politic path. “All those issues are very significant issues; the copyright system is a balance of interests and that has to be respected. But it doesn’t necessarily mean that everyone has the same view about the balance, and you have to have the discussions to see if it is possible to come up with a common view.”

WIPO has also recently brought out a report on Artificial Intelligence. It’s a preliminary report, but the issue is going to be “huge” for IP, Gurry believes, with many policy issues still to be explored. “Some people focus on the question of ‘What is an author?’ I think that’s like the question of the gender of angels—I don’t think that’s the main thing. I think the most important question is, ‘Can I take Sony’s repertoire of music and feed it into an algorithm to make AI-based music, or is that an infringement of copyright?’ Does an algorithm actually copy? I’m not sure it does.

“What is the status of copyright works: can you use someone’s novels to feed algorithms so that they learn how to write? And the other dimension of that question is, how would we know if you did? We are only at the very start, at the stage of trying to formulate the questions rather than find the answers.”