You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Frankfurt at 75: 1949–1973, war and peace

As the Frankfurt Book Fair celebrates its diamond jubilee, we take a daily look at its past from The Bookseller’s archives. Today, some crucial years from FBF’s initial quarter-century.

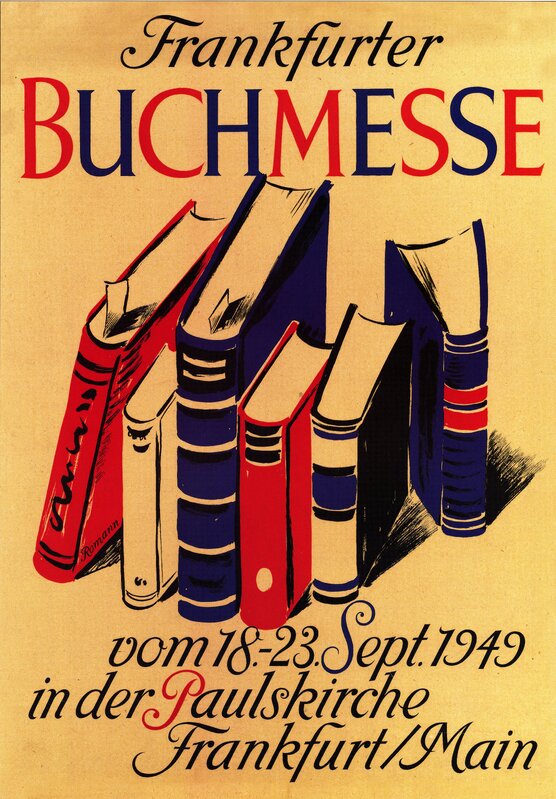

1949: It all begins

The first official Frankfurt Book Fair was hardly the first book fair in Frankfurt. There had been a regularly occurring one since at least 1462, when Johannes Gutenberg’s former associates Johann Fust and Peter Schöffer took their printing business from Mainz to Frankfurt after an acrimonious lawsuit against, and split with, the printing press creator. (It is comforting to see the book industry has remained remarkably consistent over the centuries, isn’t it?)

It is also worth noting that the first modern FBF was hardly a nation-wide celebration of books, as the Börsenverein des Deutschen Buchhandels (the German Publishers and Booksellers Association), which now runs FBF, dithered on whether to attend and there were competing fairs that autumn in Stuttgart and Hamburg. So, the Hessian Publishers and Booksellers Association put on FBF year one, holding the event in St Paul’s Church. The venue’s symbolism of the ambitions of post-war West Germany, and by extension its book trade, was telling: St Paul’s was a touchstone of German democracy—the 1848 Frankfurt Parliament was convened there—and it was rebuilt brick-by-brick after the building was flattened by an Allied bombing raid in 1944.

There were 9,046 paying customers, with around 4,000 “interested attendees” admitted for free. A “normal” stand for exhibitors was priced at DM100—around €3,100 in today’s money. The cost for an eight sq m, bare-bones System Stand Classic at FBF 2023, without any amenitites like furniture or Wi-Fi, begins at €3,897. The dealmaking was there from the off: organisers reported more than 21,000 contracts signed for a value of DM2.6m. The internationalism that would be the hallmark of future FBFs was there too, with a simultaneous French publisher exhibition at Frankfurt City Hall.

From smog-bound, rationing-wracked London The Bookseller harrumphed—in a despatch published two months after the event—that the West German book trade did not seem constrained by shortages that still hampered their British counterparts, though it noted that “interest is already strong for the 1950 Frankfurt book exposition. It may be worth paying attention to”.

1963: The British invasion

The Bookseller would become far more amenable to Frankfurt over the next 15 years; by 1963 it declared that FBF “has become the unmissable event for rights-trading and export deal-making”. And that year, for the first time, the British trade would be the biggest international territory at the Messe, with 223 exhibitors out of a total of 2,165 companies from 36 countries. It is a position it retained for many of the succeeding 60 years, although the US has often been the top foreign territory in the past two decades—at FBF 2023, the US has 389 exhibiting companies, the UK 354.

1968: Danny the Red makes his mark

FBF of 1968 was, like many events in that tumultuous year, roiled by protests including a memorable turn featuring Daniel “Dany le Rouge” Cohn-Bendit, one of the student leaders of the Paris civil unrest of the spring who would later become a Green MEP in both France and Germany. The Bookseller reported on the incident, which would lead to the public being banned from the event for two days, with wry detachment: “The 20th Frankfurt Book Fair was one to remember[...] The rebel student Daniel Cohn-Bendit got a great deal of attention. He made his first appearance at the huge reception held by the British Printing Corporation on the first day of the fair [...] although he (Mr Cohn-Bendit) did not have an invitation. By the end of the evening, there had been a minor riot, the police had been called. And there had been two punch-ups. It was dubbed the party that had everything.

“Two days later, student demonstrators arrived at a ‘teach-in’ at the stand of the publishers of Leopold Senghor, winner of the 1968 Peace Prize of the German Book Trade. So did the Frankfurt police, who closed the hall and tried to break up the meeting. On Sunday, the Peace Prize ceremony turned into a running battle. There were riot police barricades, mounted police, water cannons and supplies of tear gas. Before lunchtime, all were in action. Cohn-Bendit ran forward shouting what was reported as: ‘No peace prize for murderers.’

“Predictably, he was arrested, and equally predictably, he declined to go quietly. For a young man of his build, he put up a remarkable fight.”