You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Harkaway at world’s end

When it was announced that sometime screenwriter Nick Harkaway was writing a novel, much of the attention focused on his famous father – and in books, none come more famous than legendary spy novelist John le Carré. But when the 600-page The Gone-Away World emerged, replete with ninjas, pirates, comedy and a weapon that could destroy the world, it was so exuberant that the focus became Harkaway’s extraordinary imagination. Now, his second 600-page novel, Angelmaker, has appeared, a similarly thrilling melange of spies, gangsters, comedy and a weapon that can destroy the world – or rather, make it destroy itself.

The weapon of Angelmaker is named the Apprehension Engine and serves one purpose: to make people understand the truth. Tangled up in a plot to unleash this terror are gangster’s son Joe Spork, a clockwork expert trying to avoid becoming his departed father, and Edie Bannister, a very old former spy who’s still got come tricks up her sleeve and knows more than she’s letting on. Throw in mad monks whose ethos springs from the Arts and Crafts Movement – hence, Ruskinites – an evil genius and a bit with a dog, and you get perhaps the most entertaining read of the year. But then, ‘entertaining’ can be a blessing as well as a curse…

Ed Wood: Do you think that the few slightly sniffy reviews you received for The Gone-Away World were because it was simply too much fun?

Nick Harkaway: It’s that idea that if you’re having fun, or what you’re doing is fun, you’re somehow being less profound than if you’re being miserable. It’s as if the perfect statement of sort of profundity in writing is a book in which nothing happens until page 300, when the hero decides to kill himself. Maybe it’s an English thing: if you’re not in a state of sorrow, you’re being frivolous. And it’s funny because there are some amazing writers who do know how to have fun. I always think Pratchett is underrated on that basis; but I think when you read some of his books, there’s a deep vain of really gutsy dissection of the way we relate to one another, and how we tell stories and what stories mean to us in real life. Yet nobody goes after that, everyone says, “He’s a terrific comic writer,” which he is, but they don’t kind of say, “Actually this guy’s really really smart,” or at least I would not expect to see that in the literary section of a broadsheet, because he’s having fun and because he writes about goblins. But I’d much rather be on my side of the curtain in that context. I get to have it both ways, because I have a publisher who publishes me as a literary writer and yet, at the same time, I get to write about pirates and ninjas, mad monks and Doomsday machines.

EW: And you are often compared to another of those ‘fun’ writers, Douglas Adams.

NH: I can’t think of anything more flattering. I grew up on the Hitchhiker’s Guide, it’s just an absolutely wonderful thing to say. You know, you can argue whether or not he was a great prose stylist, but he was a terrific storyteller and a tremendous writer, and a man who cares, which is another thing that I think really matters. I get these wonderful hyberbloic comparisons – “This is like Dickens,” because if I do characters, then it’s like Dickens. But what’s interesting is no one says this continues the tradition of examination of human society which began with H.G. Wells or Jack London. London wrote about biological warfare, which I reference in Angelmaker: a story about a guy who’s travelling around South-East Asia with mosquitoes in little test tubes, so he can release diseases.

EW: So let’s talk a bit about your new book Angelmaker. One of the things you say in the acknowledgements is “This book, or perhaps its author, required some kicking around,” which suggests a kind of second-album syndrome. Did you have difficulties writing this second book?

NH: No, no it wasn’t like that. I was already writing it when The Gone-Away World was coming out... It was the end sequence[that gave me problems]. I began with an impossible crazed situation, which doesn’t appear in this final draft – a man and an elephant falling from the sky together. That crazy moment drove me in the wrong direction for quite some time, and the bulk of the external kicking came from my wife, who looked at the first ending I came up with and said it was just incoherent. And then we had various versions of an elongated editorial process, and the book profited from it.

EW: Do you think you learned from the process of writing The Gone-Away World?

NH: Yeah absolutely, you do things differently the second time round. There are obvious differences – a third-person narrator, two points of view, it’s definitely a different book. And the third novel will be different again.

EW: And the world of Angelmaker is different too, only set slightly in the future by a couple of years, and truer to life than that of the post-apocalyptic The Gone-Away World. Did you feel you could focus less on world building and more on the story?

NH: There definitely are constraints in the things you can’t do, you can’t just produce an airship or something. It’s nice to give people a couple of indicators that the world is a little different and a little more extreme. There’s no book in the world that’s even long enough to describe even one room in perfect detail, so you will have to assume that people will make stuff up for themselves and you need to give them the material to do that.

EW: You also have the macguffin of the world-ending weapon in both books…

NH: It’s definitely a macguffin. Somebody was saying to me the other day that we’re all nuclear-generation kids. We grew up reading those crazy historical pieces about how the world was going to end; it was part of our horizon, and I’m continually delighted that it didn’t. At the same time, with any piece of fiction which features a looming crisis, you’ve got several things going on: first, you have a ticking clock, which helps enormously with drama; second, more importantly, people will function in extremete ways – they reveal themselves, this is why The Day of the Triffids works, why 28 Days Later works, because the perception is that under stress we reveal the truth of ourselves. Actually if you look at the last decade you can say it’s pretty true: when danger’s in the air and we’re stressed, all of a sudden our protestations about how we’re the greatest democracy in the world become a bit tarnished, and we suddenly start sending people to Syria and Libya to have them tortured.

EW: How did you come up with this device in Angelmaker, the Apprehension Engine, which reveals truth to everyone?

NH: I saw a broken clockwork toy – it was so sweet and irresistible as an object – which made me think of a machine that made the world better. Then when you start talking about that, you have to ask what ‘better’ actually means. For a while, I contemplated a machine that makes everyone in the world nicer by about three per cent: that’s actually quite frightening, Orwellian... When you think about being pushed in a given direction by a mechanical machine, it can become quite frightening quite quickly. Quite a lot of the time, the things we are scared of in the real world are the real world implications of quite simple, abstract, philosophical problems. “How can you ever really know anything?” is a really good question. The answer is you can’t. The more you try to be absolutely certain about things, the more dangerous you become because you demand the right to surveille everybody, because you want to know that everyone is absolutely safe.

EW: Did you aim to write this as a satire? It’s full of references to bankers, politics and corruption.

NH: I’m not a solemn person, so it was always going to be playful. I send up bureacracy and have fun with the James Bond sort of vibe. But I think I’m just presenting the political climate – I wish I was satirising it.

EW: There even seems to be a reference to the 2011 August riots towards the end.

NH: The riots were after [I wrote Angelmaker], and a fantastic example of its context. Everybody in the political spectrum said how unrelated and baseless these riots were, nothing to do with economic situation, nothing to do with prevailing climate, nothing to do with Thatcher’s “There’s no such thing as society”, nothing to do with the Labour years – just all about being baselessly wicked. Interesting how many community workers were telling people this would happen and no one was listening.

EW: How did you start creating this large cast of extraordinary characters?

NH: They come from the story: there’s a hole in the story where a person needs to be; that person is going to have a bunch of tasks and that then tells me the shape of what they need to be. You either give them a phyiscal shape which is appropriate to their tasks, or inappropriate to their tasks. Having said, Joe, Edie and the story they developed together. When I first thought about Edie, it was old Edie –this forceful, magnificent, retired but still functional spy. There’s a woman who took breakfast down the road who was like Edie – she was a radar operator. She used to sit next to one of those concrete sound barriers and listen to sound of approaching planes, waiting in the dark, waiting for the planes to come.

EW: And Joe is the coming-of-age story isn’t he?

NH: There’s a dynastic thing in the book, where we meet Edie when she’s young and she carries the torch for a long time and she’s carrying a whole burden which she then passes on to Joe and to [Joe’s girlfriend] Polly; and Joe is receiving inheritance from other places. I feel really strongly about history being a deep well of trouble that occasionally spouts difficulty in the modern world. Politicans are very fond of this assanine expression, “We’re going to draw a line under that.” Well, that’s fine, but history doesn’t give a monkeys for your lying. Edie obviously can’t carry that theme because she’s the past.

EW: But also the book is about a young man not being able to help going into his father’s career…

NH: Guilty as charged! And also obviously, it is my profound delight, my dad is one of the writers who took the Buchan spy story and turned it into The Spy Who Came in from the Cold. It’s great fun for me to turn it back again and do the completely ridiculous, twist his tail a bit like that. The great thing is, he finds it funny too. But though we have the same political concerns – about how to be human, really –stylistically we’re different. Despite being he is an optimist, his writing is less optimistic, and at the moment quite savage. I think he’s enormously disappointed with how some of the things have played out in the last couple of years. I’m also disappointed and spiky about those things, but I do think it’s beatable. The good guys can win.

EW: Angelmaker does feel optimistic, and in some ways maybe a bit sentimental.

NH: I think that’s totally fair. I refuse to be frightened of sentiment. The odd thing is that if you try and be completely rational, you miss the other stuff in the world. I reckon if you went out and asked people who were in the riots for good stories they were they – about when you fall and break and ankle, and someone stops burning a car to come and help you out. No one goes looking for those stories. What they go looking for, understandably, is the story about someone falling over and immediately getting mugged, which happened. It’s about whether or not you’re in the mood to see someone else as a human being… if we’re going to make it through the century, we have to find a lot more in the way of trust. It’s extraordinary how backwards we’ve gone since 2001 in terms of civil liberties and our understanding that we’re all people.

EW: The heroes here are predominantly driven by who they love.

NH: That’s true too. Since becoming a dad, I absolutely understand the crazy insane right-wing pose people take. When my wife was pregnant I was wondering around as this crazed neanderthal. People do act for love and affection in completely irrational and magnificent ways, but it can also take you into some terribly dangerous places.

EW: At the heart of the novel is strange religious order, the Ruskinites, based on the Arts and Crafts Movement.

NH: I like Ruskin and his approach. I’m persuaded by that idea that an object made by hand has a narrative. I find machine-made objects not just bland but dehumanised. I love the ethos of baroque stuff and I’m a big fan of steampunk. As far as I know, I’m the first person to connect Ruskin with steampunk: the steampunk link comes in because I wanted grandeur of Victorian engineering. When I was learning about the Industrial Revolution at school, they said it was boring. No it’s not! It’s mad scientists! So the Ruskinites have a very gentle, artisan relationship with their god, which is slow and not charismatic, very much the sort of Church of England vibe.

EW: But then they are perverted by a villain, the Opium Kahn, who is completely evil, with no redeeming features.

NH: I have always created nuanced villains. With the villain in The Gone-Away World, you are invited to see how he becomes wicked and regret it; with the Opium Kahn, you do not. And I suppose that’s because he partly represents the figure of the British colonial fuck-up – he’s everything we ever did wrong in the world that has come back to haunt us. And obviously there’s a whisper of Bin Laden about him. He’s a genuine evil genius and a monster – with bad guys, you’ve got to believe they’re capable of doing something so appalling to the hero.

EW: And you’ve written a new non-fiction book called The Blind Giant, out in May, about the digital world. What do you think ebooks offer you personally?

NH: Maurice Sendac said, “I hate ebooks, I hope they’re not the future; I’m sure they are but I don’t care because I’ll be dead.” I like ebooks but they are a means to an end, uninspiring and basically text… I think they’re a convenience. In terms of inspiring a new way of telling stories, they’re simply not there, though the technology is approaching the point where interesting things will happen. There have been attempts to do reader-governed narratives: that completey misses the point of what reading is. It’s almost unkind to get your audience to pick your narrative. It should be, “Which of these characters are you interested in?” For me to be able to be interested, you have follow character A and, when they meet with character B, choose to follow them instead – the software has to be able to meld the story together. Bloody complicated. I would have to write decision tree that starts with one timeline, and doubles up – you’d need a writing team. Or software that can write persuasively.

EW: Where are you in the third novel?

NH: I’ve finished the first draft and it’s 100,00 words. For me that’s short. It’s a story about a guy who’s the last representative of the UK on the island, which is about to be destroyed. It’s got a slightly apocalyptic feel – because it’s about to be destroyed, everything goes Casablanca. I’m not going to say much more about it. At 100,000 words, the permutations of drama are controllable at a way in which 150,000 words are not. I realised that for every extra strand that you add, you’re not just adding length or complexity, you’re adding a series of intersections between that strand and the other strands.

EW: So, to return to our opening, you had fun with it?

NH: Oh yes, and I’m going to have more fun with it, and I’ve got a short story to write. Fun is my only barometer: if I’m having fun, you’re having fun and I can sneak stuff to you that is more profound. If it’s not fun, you’ll go and play an Xbox game or something. When I’m writing, the experience of writing has to be more fun than anything else, and that’s a high bar – after all, at the moment I could be playing with [my daughter] Clemency. But at the end of the day it is also work.

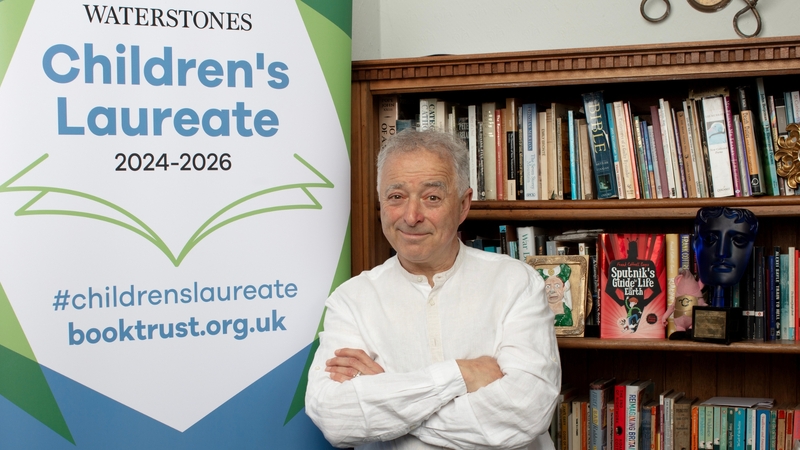

Angelmaker by Nick Harkaway is out now, published by William Heinemann. Author image courtesy of Rory Lindsay