You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

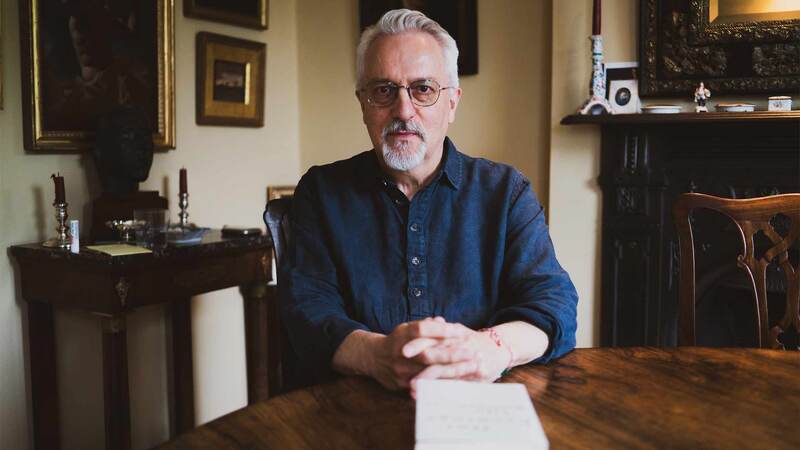

At the helm of Macmillan

"I love going to work," Macmillan c.e.o. John Sargent declares on a bright, cold New York morning, and it is palpably clear that he does. Having weathered many storms—Amazon and agency pricing most famously, and the latest, Michael Wolff’s Trump book Fire and Fury—Sargent, at 60, plans to continue to "do my thing".

In his triangular prow of an office on the 19th floor of the 22-storey Flatiron Building, a Manhattan landmark since it first scraped the sky in 1902, he can venture out on to a small balcony and survey the city, taking in a marvellous sweep from Madison Square, Fifth Avenue and Broadway, across to the Hudson River, very much captain of the Macmillan ship.

As executive vice-president of the Stuttgart-based Holtzbrinck Publishing Group, he is one of three executive board members, along with family scion Stefan von Holtzbrinck and chief finance officer Jens Schwanewedel. Separate out Holtzbrinck’s 53% stake in Springer Nature, and effectively Sargent is in charge of around 85% of the rest of the company’s holdings, comprising the higher education Macmillan Learning; the trade firm Macmillan Publishers; and Buchverlage, the combined German trade imprints. Where once he had 34 direct reports, now there are a streamlined seven. Three are not in New York: Joerg Pfuhl, head of the German trade group; Ross Gibb, in charge of Pan Macmillan Australia; and Anthony Forbes Watson, overseeing the UK, India and South Africa.

In the family

In the family

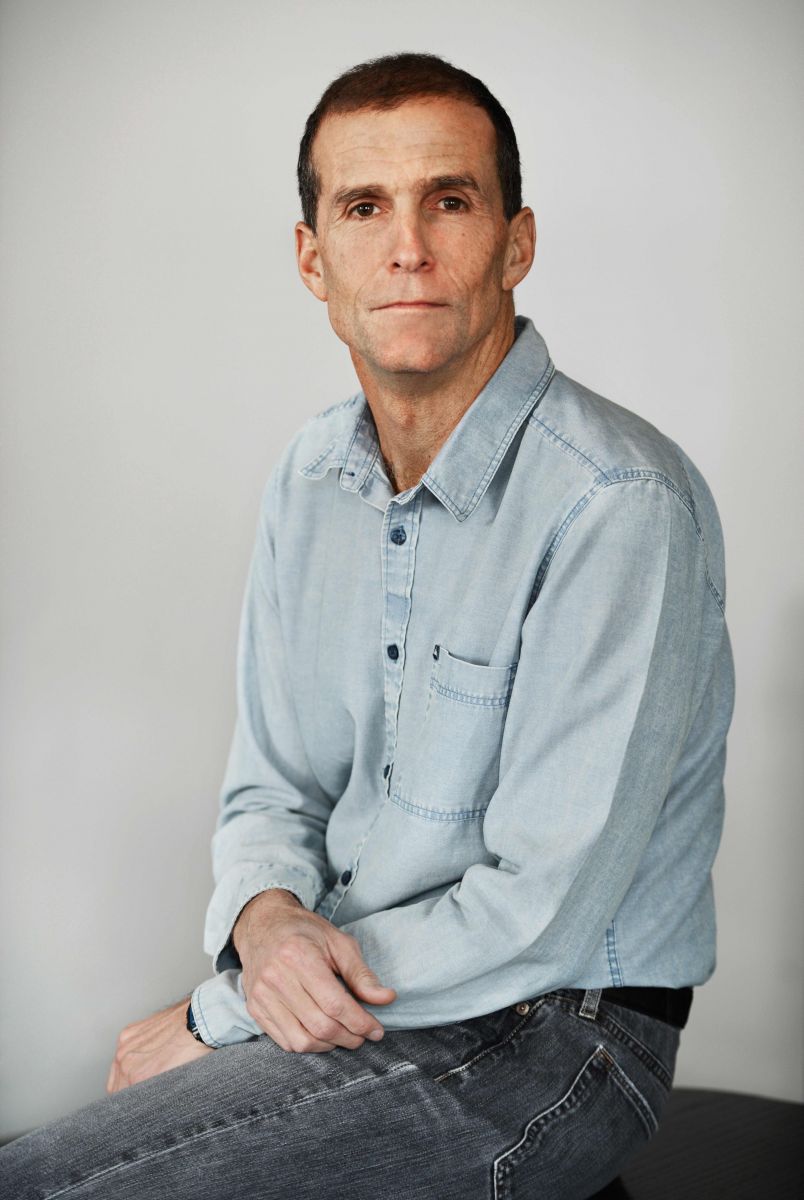

Sargent started in books as a rep at text publisher D Van Nostrand in 1983, but within a few years migrated to Doubleday, the company co-founded by his great-grandfather, F N Doubleday, in 1897. His grandfather Nelson took over from F N, and Sargent’s father, John Turner Sargent Sr, who married Nelson’s daughter Neltje, ran the company from 1963 until 1978. A much-liked bon vivant who greatly expanded Doubleday, John Sr died six years ago. After divorcing him in 1965, Sargent’s strong-willed mother, an abstract painter, took her son and daughter to live on a Wyoming ranch. Something of the lean, fit, straight-talking, look-you-in-the-eye westerner of myth and movies defines Sargent, who has visited the ranch every single year since he left. That fitness is maintained by an all-seasons passion quite foreign to Wyoming: surfing.

Ambition and drive

There’s also the drive, ambition, and energy of New York in this fourth-generation publisher, with his Stanford BA in economics and an MBA from Columbia. His first stint at Holtzbrinck was as c.e.o. of St Martin’s Press; before that, he was c.e.o. of Dorling Kindersley, and ran S&S’ kids’ division.

In the US, Macmillan ranks fifth (in the UK, it’s fourth) among the Big Five, with Penguin Random House’s size overshadowing the rest. That doesn’t seem to bother Sargent. He sees his domain as "a federation of autonomous companies. We believe in smaller operating units—that’s worked for us. We grow in spurts, a few additions at a time, and plan to continue as long as it works. At the same time, the world is changing, and we have to adjust and look for more efficiency."

In recent years, a steady stream of highly experienced publishers have found their way to Macmillan: Bob Miller, ex-Hyperion, started Flatiron; Jamie Raab and Deb Futter, ex-Grand Central, are creating Celadon; former Hyperion editor-in-chief and bestselling author Will Schwalbe has started a joint imprint with the New York Public Library; then, in London there’s Carole Tonkinson’s Bluebird, and the Collector’s Library. Forbes Watson has done an "incredible" job of infusing spirit into the UK, Sargent emphasises. "Anthony doesn’t do things the same way as me, but it’s remarkably rewarding seeing him form a team with the same urge to grow organically."

Though some have the impression that Macmillan’s global components engage less with each other than the other Big Five, Sargent counters that "we’ve benchmarked how much we do together, compared to other houses, and we are fine." Certainly, the intent, where possible, is "to encourage working across the Atlantic. The US and UK have done lots on the children’s front, and in 2019, we’re both publishing Elton John’s memoir".

Yet Fire and Fury is published by Little, Brown, not Pan Mac, in the UK. "Globally, it was very hard to predict as a big book," Sargent maintains. "That’s why Michael Wolff’s agent, Andrew Wylie, is busy selling rights to other territories now." In fact, in the US, the contract that Wolff signed with his old friend, Holt publisher Steve Rubin, wasn’t originally for a Trump book at all, Sargent explains; it was supposed to be a book about Fox News.

Very few people (including Trump) expected that he would be elected; when he was, Wolff and Wylie proposed that the journalist write a book about Trump’s first 100 days in office instead. Wolff and Trump were known to each other—often hunting in the same Manhattan social waters—and the latter, it appears, believed that what came from Wolff’s visits to the White House would be sympathetic. With extraordinary access, 100 days extended to 200, Macmillan agreed to increase the book’s scope.

Potential bestseller

"We knew the nature of what we had," Sargent says. "We just didn’t know what the response would be." The manuscript was vetted by lawyers both inside and outside the house.

"We always thought there was the potential for it to be big: we had orders for 60,000 copies, and had decided on a very aggressive print run, 150,000 books. That’s more than what most publishers would do," Sargent asserts.

But then the book leaked a week ahead of publication. Trump reacted via his lawyer at 7 a.m. on a Thursday morning with a "cease and desist" demand. That afternoon, Macmillan moved publication to the very next day. On Monday Sargent sent a memo to staff, explaining the First Amendment rationale for the company’s stand and the unconstitutional nature of Trump’s attempt to quash publication by "prior restraint".

"Never in a million years could we have predicted that reaction," he says, with amazement still in his voice. The majority of the work at that point became "a logistical problem". Macmillan went back to retailers, and "getting 1.5 million copies printed and distributed very quickly is not easy, and involved a lot of co-ordination. At its peak, velocity was absolutely incredible. It’s slowed, but the book is still selling at a terrific pace."

Fire exits

In retrospect, had they known that Fire and Fury was going to be this big, "we would have found ways to lock down the PDF more tightly, and done more to prevent piracy. It’s not something we’re used to, WikiLeaks forcing out a book!"

He hopes the Fire and Fury experience will yield useful lessons for Flatiron’s publication of former FBI director James Comey’s book in May. The Wolff brouhaha is sure to increase demand for Comey’s title. The company’s security "is tight". Sargent smiles: "It’s a good book."

No smile when he’s asked about Macmillan’s relationship with Bill O’Reilly, the former Fox News star pushed out by the network last April, after revelations of his payments to settle sexual harassment cases became public. Sargent referred to Holt’s April statement—that it had "no intention of altering its support" for O’Reilly, whom Rubin brought with him to Holt from Doubleday—as the last word: uncharacteristically, he had nothing more to say on the subject.

The matter of the First Amendment, and a publisher’s responsibility "to make public", is something that obviously exercises Sargent. Last April, at its gala, PEN presented him with its 2017 Publisher Honoree Award. He recalled in his speech how "demoralised" he’d been at S&S in 1991, when he saw how "corporate guys pulled American Psycho".

Going ahead with the Wolff book, he says, was "easy", but "given the rise of the alt-right, what to publish and what not to publish is now an extremely difficult decision." Drawing the line on hate speech is "a book-by-book decision. Publishers should be careful: we should publish across the spectrum for everybody, not just from the point of view of our industry’s employee base. What’s important is the conversation: The right answer is not to silence, but to encourage conversation in a well-meaning way, especially for younger people. At a time when the US is so ideologically split, we should be publishing books for the country as a whole."

On Amazon, Sargent says: "I have huge respect for the company and those who work there: they’re extremely creative, hard-working, ambitious [people]. Amazon has done a lot for the business, and the problems it poses are due to its success. These are the same problems we’ve always had, with one player being very powerful. Our job with Amazon is to sell a lot of books, and at the same time, make sure that the whole ecosystem of publishing remains stable and functions at the highest level. We have to resolve conflicts as best we can.

"It’s important that we have flourishing bricks-and-mortar stores, and multiple store types. In the past 10 years, it’s become clear that Americans want bookshops in their towns. The question is how best to accomplish it." As for Barnes & Noble, he says: "I’m not in the business of giving retailers advice. Its new management is working very hard—they listen. They are working with us, and we are working with them."

Before the end of next year, Sargent will give up the splendid view from his ship’s prow to move down to the financial district, to the Equitable Building, at 120 Broadway. All Macmillan trade companies — including Farrar, Straus, which has always been in a separate location — will be together on five floors.

Two years ago, Sargent took a nine-week sabbatical—Australia, the Maldives, Wyoming, the Canadian Rockies—with no screens, phones, devices of any kind. It was great for thinking, recharging and coming back to the job. Now, he continues to see "lots of opportunity, energy, enthusiasm", and is optimistic about where the trade (and he) "will be five to 10 years from now".