You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Indonesia and its 'islands of inspiration' set to star at LBF

The most striking thing about Indonesia, says Paul Smith, British Council director in the country, “is its sheer diversity: with 17,000 islands, and as many local cultural traditions, there are countless stories yet to be told to the rest of the world”.

Smith believes that Indonesian writing has a lot to offer international publishers, as it assumes the mantle of this year’s London Book Fair Market Focus. He says: “On numerous important questions facing the West, Indonesia and its literature have a great deal to share. It’s the largest Muslim-majority country [in the world] and its stories offer a window into the realities of lives touched by Islam, in a society that accommodates Muslim and non-Muslim communities harmoniously. As home to some of the planet’s greatest biodiversity, Indonesia has stories of the natural world to inspire Western readers; and from a nation often haunted by its complex history, Indonesian literature explores the way a country can come to terms with its past.”

It is a complex country, home to 726 local languages, in addition to the national language, Indonesian. It is the biggest producer of books in Southeast Asia and a large consumer of foreign titles. According to data from its national Creative Economy Agency (Bekraf), in 2016 the publishing industry contributed 6.3% of Indonesia’s GDP (the IMF estimates the country’s total GDP at $1.1tn), making it the fifth-largest creative industry in the country.

John McGlynn, co-founder of the Lontar Foundation and a member of Indonesia’s National Book Committee, describes the country’s publishing landscape as “vibrant and messy at the same time”. While the industry has struggled with assumptions that people have little interest in reading and the nation’s troubled past (during the authoritarian New Order regime, from 1966 to 1998, journalists and writers faced bans, imprisonment, kidnappings and torture, while 75% of the country’s publishers closed), its book trade is a growing player on the international stage, and has a lot to offer foreign publishers.

The Indonesian Publishers Association has 711 active members; the majority (60%) are academic and educational houses, and 65% are classified as small publishers. The country’s population exceeds 260 million and almost 60% live on Java. Ninety per cent of Indonesian publishers are based on the island with nearly 38% located in the capital city, Jakarta.

Bestselling author Andrea Hirata has opened what he describes as "Indonesia's first literary museum" in his hometown on the island of Belitung (photo credit: Sian Cain)

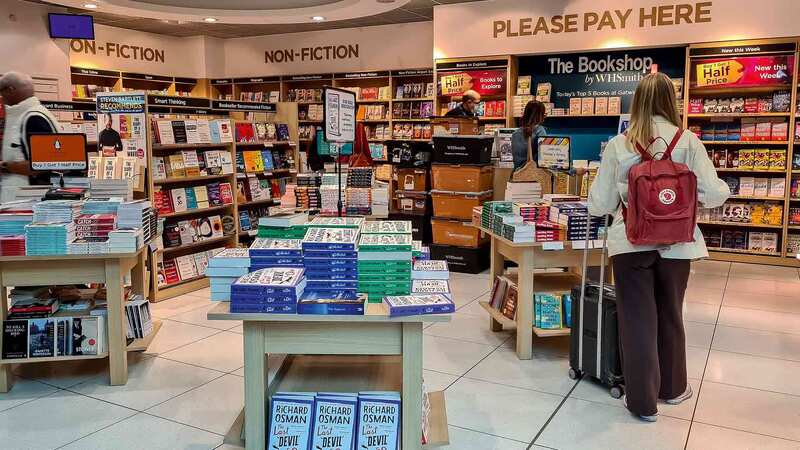

The retail picture

Bookselling is dominated by Toko Buku Gramedia (Gramedia Bookstore), which is owned by Indonesian media conglomerate Kompas Gramedia. Of the 1,200 bookshops in the country, 336 are owned by nine big players and 113 are owned by Gramedia. The company also has a publishing arm and an e-book store, Gramediana, which offers access to 12,000 e-book titles. Influential indies include Jakarta’s Post Santa Bookshop—which is based in Pasar Santa, a traditional market turned fashionable hangout spot, and runs a publishing arm as well as workshops and events promoting indie publishers—and Kios Ojo Keos, a bookshop run by indie rock band Efek Rumah Kaca that hosts gigs and speaks out on political and human rights issues.

Digital is set to be the growth area in the country. Indonesia’s overall e-commerce market was valued at £6.25bn by analyst McKinsey in 2017; it estimated that it could mushroom to £43bn–£51bn by 2022. The e-book and self-publishing markets are growing. Publishers are increasingly finding writers through social media and digital platforms such as Wattpad, which is hugely popular in Indonesia. Most deals are struck directly between author and publisher, as literary agents are not prevalent.

According to Smith, since the fall of the New Order, there has been an emergence of writers exploring freedom of expression, with a focus on a range of topics around identity and inclusivity. This can be seen in the work of some of the Indonesian authors who will be visiting this year’s LBF. The selected dozen hail from diverse backgrounds and represent a variety of genres. They include: LBF’s Author of the Day on Wednesday 13th March, Seno Gumira Ajidarma; Intan Paramaditha, whose feminist short-story collection Apple and Knife was published by Harvill Secker in the UK in December; queer Catholic poet and writer Norman Erikson Pasaribu; and Reda Gaudiamo and Clara Ng, who are among a growing number of children’s writers tackling contemporary issues in their books.

Top row: LBF visiting authors Agustinus Wibowo, Clara Ng, Dewi Lestari and Faisal Oddang.

Second row: Intan Paramaditha, Laksmi Pamuntjak, Leila S Chudori and Nirwan Dewanto.

Bottom row: Norman Erikson Pasaribu, Reda Gaudiamo, Seno Gumira Ajidarma and Sheila R Putri.

When it comes to domestic book sales, non-fiction sells strongly, with the majority of bestselling native and translated adult books being reference and how-to titles. The top native children’s titles are also non-fiction, mainly educational and religious books, but the bestselling translated children’s books are encyclopedias, fiction and activity books. The popularity of fiction is growing, though. Sales of children’s books took the largest share of the market for the five years before 2018; last year, the fiction category surpassed it.

Rights activity has increased greatly in Indonesia in the past five years, no doubt helped by being Frankfurt Book Fair’s Guest of Honour in 2015 (1,034 deals have been concluded since this time). Children’s dominates Indonesia’s rights market—in the past four years, 42.1% of publishers’ rights revenue was generated from the kids’ sector. The biggest markets for general children’s rights are other Asian countries, while those with Islamic content are particularly successful in Malaysia and Turkey.

Facts and fiction

Despite Indonesia’s recent initiatives to promote its book industry, its high population, combined with poor infrastructure, means that several remote places do not have access to books. Additionally, the number of new titles published per year per citizen is very low compared to other Southeast Asian countries.

Historically, the idea that Indonesians are not interested in reading has pervaded, but several figures refute this. Andri Gunawan, founder of the Tangerang branch of Komunitas Motor Literasi (Literacy Motorbike Community), says: “It’s not that there’s no interest in reading—there are no books.” Gunawan, whose 200-strong motorbike operators deliver books throughout the Banten region, is one of several people at grassroots level who are trying to improve access to reading through community and mobile libraries.

Sutino Hadi distributes books to children in the in the district of Tanah Abang, central Jakarta via his mobile library Bio Bemo Baca (photo credit: Sian Cain)

In early 2016, the National Book Committee was formed as a link between the government and the private sector to maintain Indonesia’s presence at international book fairs and to introduce Indonesian writers and intellectuals on the world stage. Laura Prinsloo, head of the National Book Committee and managing director of publishing and printing house Kesaint Blanc, says the LBF Market Focus will “boost translation rights and international exposure towards Indonesian literature”. The focus will be on selling translation and IP in all genres, but mainly fiction, children’s, non-fiction, comics and cookbooks.

As Indonesia heads towards a general election in April, the country is quite tense politically, but its book trade is positive about the future. Hilmar Farid, director general at the ministry of education and culture, expects that, as a result of Indonesia’s participation at LBF, “ideas in the form of books will have a ripple effect on other cultural industries”.