You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Jung Chang: China Revealed

It’s testament to the esteem in which Jung Chang is held by the public that, having not released a new book since her biography of Mao in 2005, her second after the 13-million-selling Wild Swans 21 years ago, she could probably have sold out the second biggest venue at the Hay Festival twice over. It was standing room only to hear the story of her family’s past (which informed Wild Swans) and China’s present – and what a story it was.

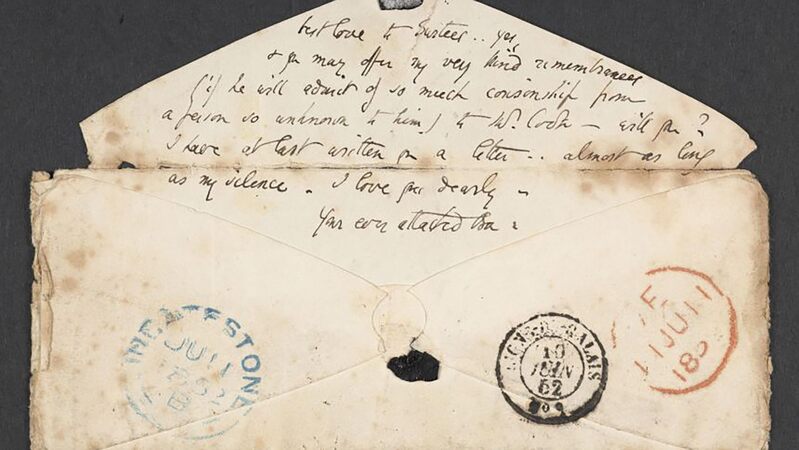

She began by relating the life of her grandmother. Born in Manchuria in 1909, her feet were bound in the traditional style: the arches and bones broken with large stones, and all but the big toe bound to stop the feet recovering. She showed her grandmother’s shoes, as tiny as a young child’s. “You couldn’t walk normally,” said Chang. “The whole idea was to imprison women… Some men would enjoy looking at women teetering, helplessly.” She added: “I can’t think of any culture that treated its women so cruelly.”

Her grandmother was given to a warlord general as a concubine. She saw him for the first six days of their marriage before he left, only returning for a brief visit to get her pregnant. When Chang’s mother was born in 1931, her grandmother realised that the baby would be snatched from her to be brought up by the warlord’s “proper wife”, so she fled. She fell in love again, but with a man who already had a family – the eldest son shot himself at disgust in his father becoming involved with a former concubine. They moved on again.

During the civil war, Chang’s mother, now grown up and an idealistic Communist, discovered that her beliefs didn’t stand for much in the China that was emerging. “When she met a real Communist, she was disappointed,” said Chang. “There was no equality.”

Part of the lack of equality came in the comparison of her life with that of her husband, and Chang’s father, a Communist officer, who was granted rights to such privileges as rice. By the time she was born, the standing of Chang’s family raised them up from the majority.

“I myself was born in China in 1952,” said Chang. “I grew up in Mao’s China in the privileged world of the Communist elite.” Chang raised a laugh when she said, “When I first came to Britain, my view was that it was wonderfully classless.”

This was a period of isolation, and Chang said she never even saw a foreigner until she was 23. Growing up, children were told that the West was a place of terrible hardship and cruelty, where children starved and drinking Coca-Cola was a sign of evil (as portrayed in propaganda films). “We all thought ‘hello’ was a swear word!”

“I first started questioning the society when I was 16, when the Cultural Revolution started in 1966,” Chang remembered. That year, she went on a pilgrimage to see the God-like Mao in Beijing, but only succeeded in seeing his back – she says she considered suicide as a result. But her faith quickly began to wane as she became aware of atrocities and the destruction of China’s most precious ancient buildings. “I started to fear, to hate and to dread the society I was living in,” said Chang.

Family life became impossible. Chang’s father stood up to Mao, and as a result was tortured, imprisoned and went insane, dying in exile. When her mother refused to denounce her father, despite their very difficult relationship (Chang says her father always put his ideals ahead of them), she was punished with more than 100 public denunciation meetings where she was beaten, spat on by children and made to kneel on broken glass. (Chang added that all teachers had to undergo these meetings, to propagate violence amid their pupils). “She survived, she still lives in China,” Chang said.

In 1978, two years after Mao’s death, Chang was lucky enough to come to the UK as one of a very small group of students, who were nevertheless made to dress in Mao suits and told not to mingle. They were told that the pub was “something indecent, with nude ladies gyrating”. When, one day, she risked everything by ducking in there, still convinced the Chinese embassy had eyes everywhere, she was disappointed to only find old men drinking.

“Life was so exciting,” said Chang. “I was one of the first group of 14 people who left China to learn English.” As far as Chang knows, she was the first person from mainland China to earn a doctorate from as UK university, in 1982. She was also the first, she believes, to have a foreign (British) boyfriend. “It was then that I started to use make-up because I thought that would provide a disguise from the embassy.”

The last thing she wanted to do during this period was think of her home country, especially as many in the West had swallowed the myth of Mao the people’s hero – she told people she was from South Korea just to avoid the conversation. “I don’t blame people because China was isolated and the war, from outside, was propaganda.” Even to her, for a long time “Mao was unquestionable… we blamed Madame Mao for all the terrible things… Never underestimate the power of brainwashing.”

“I had always wanted to be a writer,” Chang continued, “but to write would mean to look inward and backward, which was not something I wanted to do.” What changed things was a visit from Chang’s mother in 1988, who “felt the need to open her heart”. She stayed for six months and they spoke of her past continually. She left Chang with 60 hours of recordings. “I thought I could write something about what life was really like,” she said. That writing became Wild Swans.

Seven years ago, Chang released her epic biography of Mao, written in collaboration with her husband Jon Halliday. “The world knew so astonishingly little about this man who turned the lives of a quarter of the world’s population upside down,” said Chang.

Chang herself researched the Chinese materials for her book; Halliday, “unfortunately [for him], spoke many languages, so researched the rest of the world”. The book took them 12 years to create, a fact that drew gasps from the crowd.

“I did come to understand him [Mao], but not excuse him,” said Chang. “I knew he was bad, I just didn’t know he was that bad.”

She used the example of the famine that killed 14 million people. Chang had always assumed the cause was economic mismanagement, but found that Mao, pursuing his aim to rule the world militarily, had been buying cutting-edge arms (including nuclear weapons) from Russia. The price was high, however – “He exported the food his people were dependent on… he knew his people would die.” She discovered, sickeningly, that Mao had said: “Death has benefits: it can fertilise the land.” For all of his projects to pay off, Mao had calculated that half of China may have to die.

Both of Chang’s books are banned in China, though her own translation of Mao is available in Hong Kong and has also been downloaded in pirated and scanned editions in China. “But China also has a huge internet police,” said Chang, explaining how she was once reading a blog about the book and Mao and it vanished, leaving only a box informing her the site had been censored. “You always have the fear your computer will be targeted… there is still a strong culture of fear.”

While Chang was hardly positive about China’s current situation, she did say things had improved for nearly everyone to some extent, and for the middle-class life is almost easy: “The culture is not as extreme as in Mao’s time, not as absolutely horrible… Now you really have to stick your neck out to get punished, but the punishment is severe.”

Most people are not willing to do that, however. “Only a few per cent of people can’t live without that freedom of expression.”

Chang’s next book will, fittingly for a woman who has tackled both women’s situation in China and its most famous leader, be about a female leader, the Empress Dowager Cixi, who brought China into modernity over four decades at the end of the 19th century but who was vilified by later governments. “She is still being maligned in China today,” said Chang. “She was a great statesman, actually, far greater than any of her modern successors.”

If her first two books are anything to go by, it will be a literary highlight of years to come.

Wild Swans and Mao are out now, published by HarperPress and Jonathan Cape respectively