You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

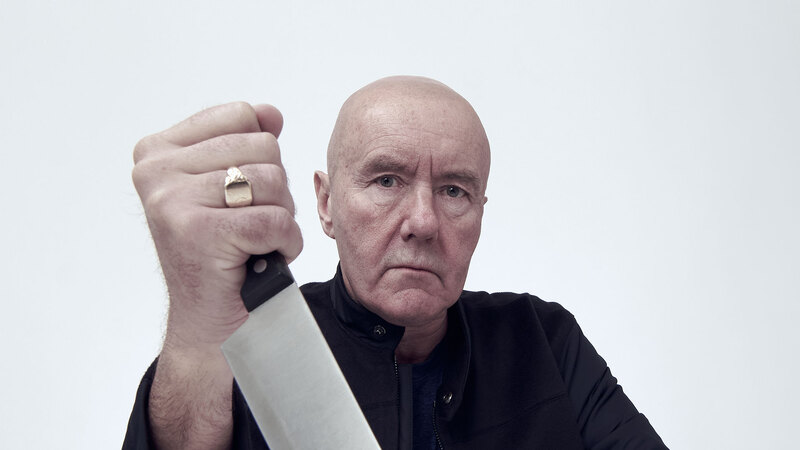

The last Train...

Can you tell us a bit about Dead Men’s Trousers and the journey the characters have gone on since Trainspotting?

It carries on from where the last book [The Blade Artist, Cape] ended: Begbie and Renton are on a plane. It’s about the characters from Trainspotting, and where they are now. They’re guys in their fifties, and they’re at a funny time in life, when you’re plodding on with your interests but also more driven to looking back on things as well. We’re living in this strange era now, whereby we’re all taking comfort in the past more than we used to because the future is very uncertain, and potentially quite dystopian.

It’s a really interesting time. These characters came into their own as being the first human victims of industrialisation, as part of the working classes. But now we’re all victims of it, really. The traditional middle classes and even the very rich are going through this existential angst; their power is going to be taken away because all the things that support hierarchy—capitalism, division of labour, gender-specific roles—are crumbling. So everybody’s in a state of anxiety, and these characters are in this state as well. It’s a different kind of ennui that they’re facing, but it’s a systemic continuation of the same thing that they had back in the day.

How do you feel about the end of the Trainspotting series?

This has to be final novel, really, unless I write about some drama taking place in an old folks home. I can’t really see these characters existing in a dynamic way anymore. I see the social and dramatic vitality of these characters as definitely being gone after this.

Why did you choose to write the series in dialect?

I started to do it in Standard English but it wasn’t coming alive; it seemed quite pretentious. The characters just weren’t talking like that, I couldn’t see them thinking like that, I couldn’t see their minds or their emotional states best rendered in that way.

The oral tradition is very big in Scotland; it’s a very performative thing. When people tell stories in bars and parties they always perform them. Standard English is an imperialistic, controlling type of language. It’s an administrators’ language, it’s a colonial language. Which is great for precision, but not very good for funk or beats, and I wanted to get a bit of funkiness into it.

I wanted to replicate the excitement of the rave in the book. I found that experimenting with language—like bringing back street language and old Scots, and the gypsy, sort of east-coast British language that permeated into Scottish housing estates in the east of Scotland—was a way to do it. I tried some typographical experiments, like words falling off pages and playing around with fonts, to simulate the kind of music and light effects of raves, too.

This issue of The Bookseller discusses the rise in Gaelic and Scots publishing. What are your thoughts on that?

We should be a multicultural society and we should be promoting diversity. We should be able to look at all the different cultures and to support all the different cultures that are coming out. In some ways it’s nice that everything is standardised, it makes life easier, it makes communication between people and understanding people easier. But we should be able to operate on two levels: a mass global communication level but also a level whereby all these different cultures and different sources of knowledge can be experienced. I think that there should be this kind of diversity in the world.

This piece is part of The Bookseller's in-depth focus on Scotland. Other stories in the focus can be read here.