You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

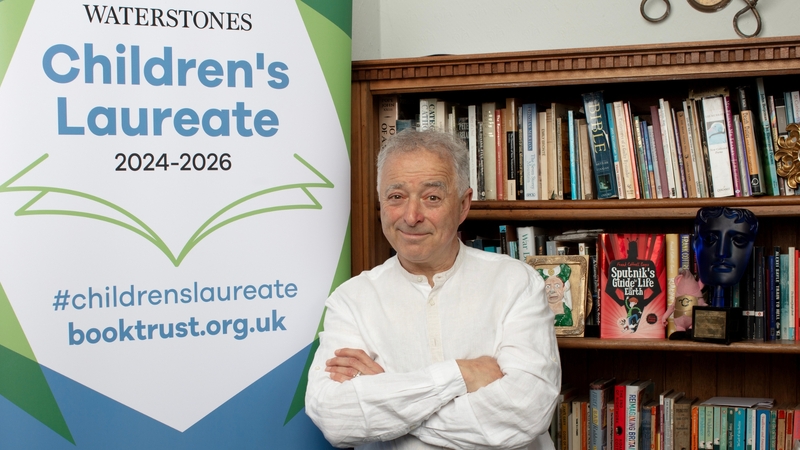

Melvyn Bragg: mind over matter

The greatest compliment you could give Melvyn Bragg about one of his recent novels? That he has the facts wrong. For the past decade and a half Bragg’s fiction has largely been based on his own life, starting with 1999’s The Soldier’s Return. But the keyword is “based”.

“There is a fundamental misunderstanding of autobiographical fiction,” he says in that famous Cumbrian drawl. “People think autobiography is memoir, and memoir therefore is fact. But I know that’s not the case. I couldn’t write a memoir because it would be too patchy and I have too much responsibility. I would have to think: ‘Did my mother really say that? Did my Aunt Mary really say that?’”

He argues that the autobiographical novelist can be more revealing than the memoirist; fiction enables a novelist to invent and reach a greater truth.

“I’ve always thought the mixture of memory and imagination is fascinating,” he says. “I misremember as much as I remember. I always thought the opening of The Soldier’s Return [meeting his father returning from the Second World War at a train station] was based on a real event. My mother read the first chapter and said: ‘This isn’t about dad, it wasn’t like that at all.’ I was completely delighted that I got it all ‘wrong’.”

Delving into the personal, however, can take its toll. Bragg’s previous novel, 2009’s Remember Me... was a beautiful but bleak account of his break-up with his first wife and her subsequent suicide.

“I probably dug too deep, and I still wonder if I should have published that,” Bragg says, his voice softening to a whisper. He paws at the table in front of him, then rubs his eyes before going on. “I didn’t want to continue writing fiction after Remember Me..., it just caved me out. I couldn’t write fiction for two or three years, it was the first time I stopped since I was 18.”

Amazing Grace

Bragg still could write non-fiction, however. Since Remember Me... he has published Book of Books, a study of the King James Bible; The South Bank Show: Final Cut, a compendium of interviews from his ITV arts programme; and In Our Time, a companion to the Radio 4 show he has fronted since 1998. Yet given the emotional toll of Remember Me..., it is somewhat surprising that his return to fiction tackles another difficult, very personal subject: his mother’s dementia.

The centre of Grace and Mary is 71-year-old London resident John, and his 90-something-year-old mother Mary, who is suffering from Alzheimer’s in a Cumbrian care home. During John’s visits to the home, the two explore the past and the narrative goes back to Mary’s childhood and early life in Cumbria. As Mary’s condition deteriorates, John attempts to “reunite” Mary with her biological mother Grace, who had to give her up for adoption. John’s research of Grace’s life stretches back into the 19th century, finding a character whose life is changed irrevocably by the First World War and a doomed love affair.

If all this sounds gloomy, it is not. The tight and compact narrative is elegiac—for Mary, and to some extent to the rural Cumbria of Bragg’s youth—and deals sympathetically with a loved one in the grip of a very cruel terminal disease. Yet in many ways the book is uplifting, a celebration of the two lead characters’ lives.

“It isn’t miserablist, but it is sometimes sad, sometimes devastating,” he says, answering a question about the tone of the novel. Then, his voice drops again, and I realise he is switching to discuss real-life visits to see his mother. “What got you was the piercingness of the illness. You never knew what she was thinking, and sometimes you thought: ‘My God, does she really know what’s going on?’”

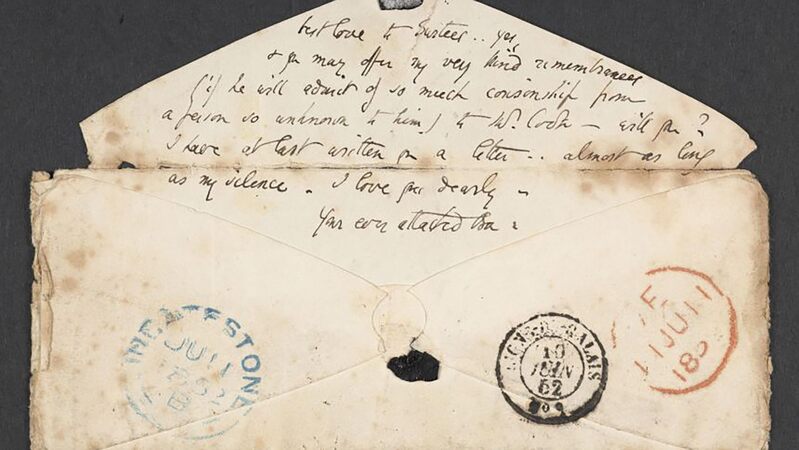

Grace, the woman based on Bragg’s biological grandmother, is almost all invention, as Bragg only had “a few archaeological scraps” of her real life. Yet he admits to also not really knowing his mother, though he was very close to her. He says: “She came from a background, a generation, that never talked about themselves. It was a sort of omertà—it was jokes, arrangements, football, politics—but nothing deeply personal.”

TV versus books

Bragg grew up in the place he sets a good part of Grace and Mary, in the small market town of Wigton, Cumbria. After reading history at Oxford, in 1961 he joined the BBC trainee scheme, the launch of his long career in front of and behind the camera. “My career’s upward trajectory ended at 24,” he says, laughing. “I was lucky enough to find something I was really interested in and once I got to run my own arts programme, that’s all I wanted to do.”

Bragg has a vast body of work: 21 novels, 14 non-fiction titles, a couple of children’s books and four screenplays, including Jesus Christ Superstar. Does he consider himself a writer or a broadcaster? “The crudest thing I can say is that I gave up broadcasting several times to write, but I’ve never given up writing for broadcasting. But I like the two running together. But early on it wasn’t like I had a choice. My books were doing OK, but I had to make a living, I had to eat.”

Writing Grace and Mary, and seeing his mother’s decline and death (she died last year aged 95), made him think about his own health and mortality: “Let’s not piss about. One of the things you think as you watch someone go through this disease is: ‘Is this going to happen to me?’ The odds are I’m going to get Alzheimer’s. And for a time, when I had a memory lapse, I thought: ‘Uh oh, is this one of the first signs?’ But if it’s there it’ll get you and I’ll meet it as it comes.”

Bragg is not exactly comfortable talking about all this—he fidgets, he pauses, his voice lowers occasionally—but he does not shirk any questions. He is rather sanguine that even though this is fiction, he is going to have to talk about his life over the next few months as he promotes the book. “It’s a personality-led culture,” he shrugs. “People are as interested, or some even more interested, in the writer than the work. But that can be a way in to a book for some people, so that’s fine.”

Grace and Mary by Melvyn Bragg is out now, published by Sceptre.