You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

mussolini's complicated love life

The day after his son was born, Mussolini was withdrawn from the intensive training course for officers and sent back to the trenches.

It can certainly be assumed he had other things on his mind that day: he was under pressure and not only because he had to fight. In December 1915 he was taken to a hospital in Treviglio for suspected paratyphoid and associated jaundice; his commanding officer sent a telegram with the news to "Signora Ida Dalser Mussolini", the mother of his son. Rachele too, as the mother of his daughter, although not yet his wife, was informed. She always tried to keep a watchful eye on Mussolini's various mistresses; at this time she regarded his relationship with Dalser as particularly threatening, while she was less concerned about [Margharita] Sarfatti.

Ida Dalser was different, however, and it was a kind of proof that she represented a serious threat when she turned up suddenly one day at the front door when Mussolini was away in Genoa. "I thought her ugly, older than me, and wearing too much make-up," [she said]. "She wouldn't tell me her name, but claimed to know all about our life together, what my husband did, and so on. I was taken aback by her audacity."

When told about the visit, Mussolini reacted with his usual cynicism. He freely admitted that he and Dalser had been lovers, and dismissed her by describing her as a crazy Austrian woman. There was some justification for his description: Ida Dalser had once set fire to a room in the Hotel Milano in a fit of hysteria. It was 15th November 1914, the day the first issue of [the newspaper founded by Mussonlini] Il Popolo d'Italia had come out. Seeing it on sale at the news-stands exacerbated Dalser's fury at having been exploited and then abandoned by Mussolini. The fire was put out and the damage assessed and a police investigation was started.

One day two policemen called at Rachele's house; she was out shopping, Mussolini was away in the war, but Rachele's mother, who was still living with them, opened the door. The two police officers announced that they had been ordered to sequester the family's belongings. It was only when she went to the police station that Rachele understood the situation. When the policemen had asked her if she was the Signora Mussolini, she automatically said she was. Then one of the officers said in that case it was clear she was guilty, since the hotel managers had accused the Signora Mussolini of setting fire to one of their rooms. It took a while to sort things out. Rachele had to prove that she had never set foot inside the Hotel Milano. Finally, by comparing statements taken from witnesses, it became clear that the person guilty of arson was another Signora Mussolini.

A good socialist wedding

Rachele immediately realised there was no time to lose. She set off to find Mussolini. On 17th December they were officially married. "As good socialists we decided to get married with a civil ceremony only. It was a very simple affair and took place in a room in the Treviglio hospital. Benito was in bed, recovering from paratyphoid but still unable to get up because of jaundice. He had a woollen beret pushed down on his nose and he was unshaven. He cracked jokes with the friends who had accompanied me on the journey from Milan, but it was obvious he was nervous. When the moment came for him to say "Yes", he said it, joyfully, in a loud clear voice. When my turn came, I at first didn't reply, pretending to be lost in thought, but watching Benito from the corner of my eye. When the presiding officer repeated his question, I remained silent. Benito had raised his head and was looking at me in amazement. At the third attempt I finally and joyfully said "Yes". He gave a sigh of relief and sank back on the pillow as if having to wait for my reply had been too much for him."

There may have been other reasons, apart from Rachele's silence before she said "Yes", for Mussolini's suddenly being overcome: he was weakened with jaundice, she had told him she was pregnant again (with Vittorio, their first son) and, possibly, he had realised that he had just committed bigamy. The accusation has never been proved with documentary evidence. We know that when he was wounded during the troop exercises in February 1917, Ida Irene Dalser came to visit him in hospital and, to gain entry to the ward, showed a document proving she was his wife. Then Rachele arrived and all hell broke loose. The two women at first ignored each other, but when they realised they were both claiming to be Mussolini's wife, they rushed up to his bed, each shouting out that she and only she had the right to stay by his bedside.

"The other soldiers in the ward were highly amused. Then something in me snapped and I threw myself at her. I even managed to put my hands round her neck and started to throttle her. Benito, all bandaged up in bed like a mummy and unable to move, made vain attempts to stop us. He even threw himself down from the bed. Luckily some doctors and nurses intervened before I strangled her. She fled away while I burst into tears."

Ida Dalser continued to maintain she was Mussolini's legally recognised wife for the rest of her short unhappy life; she declared that if she had no official documents to prove it, it was because once he had become the country's leader he had had all the evidence destroyed.

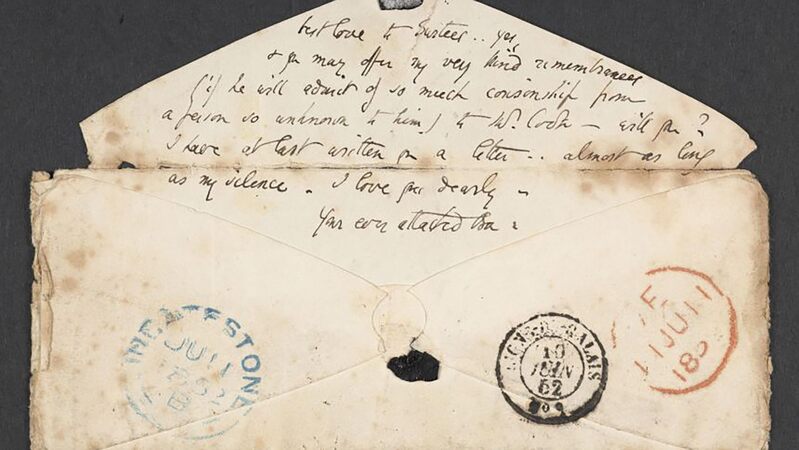

On 22nd December 1916 Mussolini obtained permission to take a long period of sick leave, until 16th January. A few days before he was due to return to his regiment, on 11th January, Dalser got him to sign an official document, drawn up by a notary, Vittorio Buffoni, acknowledging [her child] Benito Albino as his son…

Despite having to deal with this complicated situation, Mussolini was still able to use the period of sick leave to pursue other women. It was probably while he was in Milan on this occasion that he met a 23-year-old woman who would go on to become one of his longer-lasting mistresses. Alice De Fonseca Pallottelli was intelligent, cultivated, beautiful, fascinating, high-spirited and, with the typical Florentine wit she had inherited from her family, amusing. In 1917 Alice gave birth to a son, Virgilio, who as an adult would become one of the members of Mussolini's inner circle, the associates he trusted most. She also had two other children, Duilio and Adua, and, according to Claretta Petacci, claimed that Mussolini was their father. Even if their relationship did begin in 1916, it remained secret and only became known after Mussolini had seized power.

Ida Irene Dalser, on the other hand, despite being the only woman who got Mussolini to acknowledge paternity of her son, never became one of his habitual mistresses and never enjoyed the advantages which came from belonging to the circle of the women with whom he enjoyed sexual relations. She was left burnt out by her own passion for the man. He demoted her to the status of former lover and, partly because of the war and his own financial problems, both at home and with the newspaper, failed to send her the sums they had agreed for the maintenance of their son Benito Albino.

On 15th February 1916 he was once again far away from Milan and his giddy womanizing, on the Italian battle lines where, however, he was putting his pen to more use than his bayonet. Ida Irene Dalser employed the lawyer Bortolo Federici to take on her case.

On 19th May 1916 the Milan magistrates had charged Mussolini with failing to fulfil the undertakings he had agreed before the notary; he was bound to pay Dalser the monthly sum of two hundred lire. Then as now the time such conflicts took to go through the legal system was very different from that required to meet the urgent needs of the people actually affected by the problems. Ida Dalser only received the first monthly contribution from Mussolini nearly a year after the court case.

There then followed a period of calm, when it seemed that the mother of the Duce's firstborn son had indeed decided to leave him alone. But getting the agreed monthly sums proved increasingly difficult: a new storm loomed on the horizon.

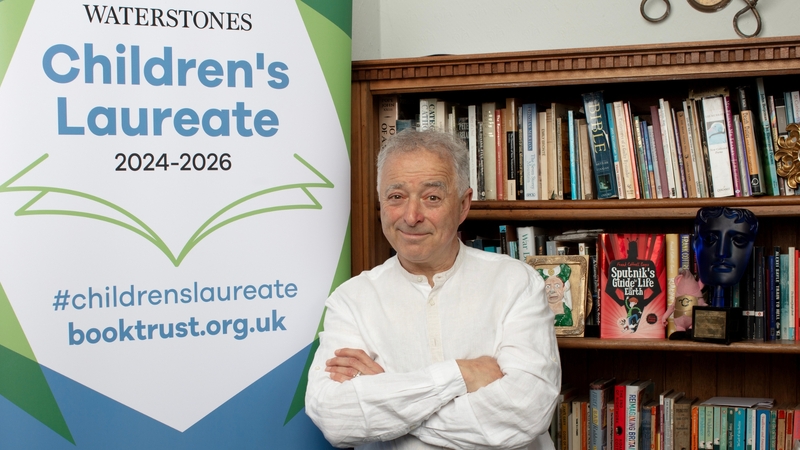

Il Duce and His Women by Roberto Olla and translated by Stephen Parkin is published by Alma Books.

Photo: Mussolini and his family: his wife Rachele, Anna Maria, Romano, Edda, Bruno and Vittorio.