You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

New era for Rainbow Nation chain

When Benjamin Trisk describes himself as the third best bookseller in the world, somehow you believe him. Trisk is chief executive of South African chain Exclusive Books, having bought the company in autumn 2013. The development marked a return to the sector for Trisk after a 30-year hiatus.

When Benjamin Trisk describes himself as the third best bookseller in the world, somehow you believe him. Trisk is chief executive of South African chain Exclusive Books, having bought the company in autumn 2013. The development marked a return to the sector for Trisk after a 30-year hiatus.

In a letter to staff sent after the acquisition, he wrote: “This is more than just a transaction for me. It is a personal journey returning a national asset to a home in which the passion is books and the cultural repository that they represent.”

Trisk began his bookselling career with Exclusive Books in 1978, when he was invited to “learn the business’ from its founder Philip Joseph, who had sold it to Premier Group Holdings. Trisk had completed an MBA and was teaching, but Premier’s chairman at the time knew that he had a passion for literature: “He told me that I was the only person who would still owe the company money for books at the end of each month after I’d been paid my salary, and he was right.”

Trisk stayed with Exclusive for five years before Premier moved him into a new corporate role. He remained outside of books until he heard that Exclusive was up for sale in February 2013. Trisk describes this time as a “large peregrination” from which he has now returned. “Of all the jobs I’ve done, the most fun I’ve ever had—and the one thing I have found more satisfying than anything else—is the feel, the smell and the texture of books.”

Exclusive has had its own eventful (and complicated) journey. The Josephs (Philip and later Richard) moved to the UK, where they established Books Etc. Exclusive Books became a division of CNA Gallo, later renamed Millennium Entertainment Group Africa (Mega). That business was swallowed by media group Johnnic, later renamed Avusa. In 2012, this group was again subsumed and renamed, as the Times Media Group. Exclusive sat in a general “books” unit, alongside the Van Schaik academic bookstore business and book publishers New Holland and Random House Struik.

Selling power

It was during this later period that the business lost momentum, as many chain stores did across the world in the face of online retail, the arrival of the e-book and the recession. Trisk calls it a “five-year crisis in bookselling”, though he does not blame external forces. “It had nothing to do with e-books, Amazon, whatever . . . It was to do with the standard of retailing. If you are a bad retailer you will go insolvent.”

He says Exclusive had lost “some focus on books—the quality of books, and the quality of curation. It was just doing the same thing, maybe a little bit better every year. What was missing from the business was a very clear vision of what needed to get done, and what systems were required.” Later, he adds that: “The corporate cannot be a good owner for a bookshop, because it will never care enough about the product.”

If it is not already clear, then it is worth stating: Trisk is a conviction bookseller. Last Christmas the chain produced a 68-page catalogue, showcasing 540 titles, without seeking advertising from publishers. “Our choice should be our choice. It was not an advertising rag for the publishers,” says Trisk. The brochure gave the business an opportunity to push its range to more customers. “We’ll never be able to have the kind of range depth of a Foyles or [Waterstones] Piccadilly. We can’t do that, but we need to open these windows as far as we can.”

He describes the relationship with publishers as “symbiotic”, particularly important considering the distance between Exclusive and the UK and overseas publishers that supply much of its stock and make up two-thirds of its sales. It can take six to seven days to air-freight titles to the country, and six to eight weeks when shipping bulk orders. “The fact that we are far away from the source is, of course, problematic. I need to commit to stock, which I try to do, but what I cannot allow is for publishers to say: ‘Exclusive has taken 1,000, so we’ll ship 1,200 and have 200 in stock.’ I need to be able to develop the market properly.” Trisk also resisted the temptation to go after extra discount from publishers. “Just taking more discount from publishers would make us fatter and lazier, not better,” he says.

Managers are encouraged to be autonomous when ordering titles, but stock levels are closely monitored. “We are buying more, every publisher will confirm that. Stock is closely controlled. We monitor returns by publisher, and by store.”

Going forward

The results have been quick to materialise. The retailer was sold to Trisk, investor Mark Barnes (now chairman), and backed by Global Capital Proprietary Ltd, for around R90m (£5m). Trisk is coy about revealing sales numbers, but reports: “We are at least twice as profitable as we were a year ago. Sales had been falling for five years, and we’ve turned that around.” Exclusive accounts for roughly half of the measured books market in South Africa. According to Nielsen BookScan SA, the market is up 4% year on year in value terms (£61m), with volume sales slightly down.

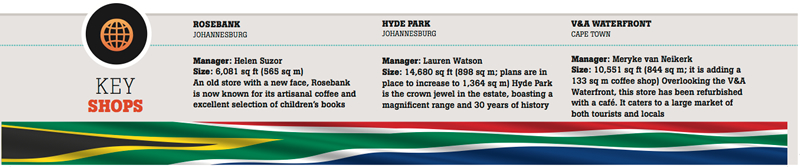

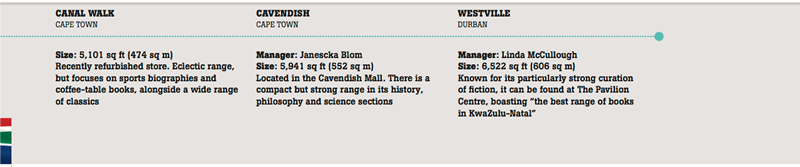

Exclusive operates 43 stores of varying sizes, including its flagship stores at Hyde Park in Johannesburg and V&A Waterfront in Cape Town. Trisk says there are “five or eight” too many, with some in the wrong location, but he says he does not plan to reduce staff numbers. Instead, he wants to turn location into an asset. “It is foolish to imagine we can compete with Amazon in their business. Where we have the advantage, is that I have 43 places where I am holding books. And if people want them, I need to be able to get books there the next day. I don’t yet have the systems for that properly, but we are getting there.”

In August, Exclusive re-opened a refurbished store in Rosebank Mall, the first designed around Trisk’s concept of “theatre”, and the first to introduce an Exclusive Café. “Our first love is literature. Our second is coffee,” the store trumpeted at launch. Trisk says: “Even in those small towns where there is nothing to do, if I can offer a great coffee venue, then [people] will go there to meet people.”

Trisk has ambitions beyond coffee—tapas. Before our meeting in London, Trisk visited Barcelona to experience the culinary scene. “I want to put the best Tapas bar south of Barcelona [in its Hyde Park store]. Tapas is about conversations, friends go and talk, people talk to strangers. It was described to me as their ‘five-play’— imagine cocooning that with books. If any country needs conversations between strangers, given the fractures we’ve had, it is South Africa.”

He is also looking overseas—possibly at continental Europe, or areas where a large English-speaking population is not well served by local bookstores. Trisk says he is backed by his board, its long-term investors and his own financial team. “I’m lucky to have a chief financial officer, Steve Thomas. He understands the controls. He’s the one who says ‘no’ to me.”

Trisk says he is also working on how to better reward staff—“we are still looking for the right mechanic to incentivise people to achieve their budgets, and then produce super profits”—and has recently introduced a staff exchange with Foyles. He has a clear message to staff: “Booksellers are the ultimate curators of the cultural fabric that exists in a society; we shape things. When we put the right books on our shelves, we shape how people see themselves, and how they talk to each other.” The third best bookseller in the world is aiming for the top.

Inside story

Inside story

Ben Williams, Sunday Times (SA) books editor

Since 2008, the story of the South African trade book market has been the tory of two numbers. First, there are roughly one million book-buyers in the country (its total population verges on 50 million). Second, they collectively purchase books worth R2bn (around £115m) each year. The challenge that booksellers contend with, then, is how to carve out an ever-larger share of the stubbornly finite spend on their products—while factoring in that Amazon has the same goal.

Exclusive Books was accustomed to leading the pack. But the chain lost momentum.

Now that it’s once again an independent retailer, however, Exclusive seems to be getting its mojo back. It has focused on its core business—range and backlist, with bestsellers sprinkled in—and publishers are praising it for its renewed vigour. If it continues its current direction, who knows?

Perhaps it will have the wherewithal to take on the larger challenge facing South African booksellers: how to turn one million book buyers into two million.