You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Passing the screen test: four speakers reveal what makes a hit TV adaptation

A rise in the number and output of streaming platforms such as Amazon Video and Netflix has opened up new and profitable revenue streams for writers—but how can publishers help them grasp them?

Has the book to screen world changed in the past year?

Tobi Coventry: I would say that it has definitely become more competitive, very much so in the five years I have been scouting. There are more scouts than before, and I think more deals being done. Producers are very keen to create projects and build relationships with key writers and directors, especially for TV and streaming, and books are a fantastic way of doing this. There is also something interesting happening with the type of books optioned and how they translate such as [Liane Moriarty’s] Big Little Lies—a very commercial book matched with quite an arthouse director to create something accessible and hard-hitting.

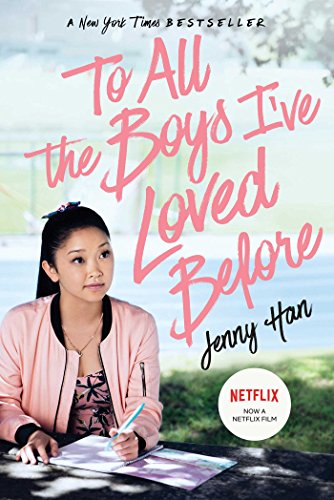

Ingrid Selberg: A year really is only a blink of an eye in this process, so I can’t really ascribe any recent developments to this past year only. The most significant recent development is the rise of Netflix and Amazon in the kids’/YA space, with both airing teen rom-coms [Beth Reekles’] The Kissing Booth and [Jenny Han’s] To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before and a number of series based on US picture books, such as Llama Llama [by Anna Dewdney]. Films largely continue to be based on big franchises— "Incredibles 2", "Hotel Transylvania 3", "Paddington".

Emily Hayward-Whitlock: For a while now, there’s been increasing competition for titles. This year has been no different. I had several titles in auctions contested by five or more companies, but lots of titles end up with two or three competing for them. In a similar vein, more and more [screen businesses] are hiring dedicated scouts, either external or in-house, to make sure they’re at the front of the queue for exciting material.

Camilla Deakin: There have been many very successful book-to-screen adaptations over the past few years, and the number is continuing to grow. New screening platforms, different formats and the resultant ever-expanding audience make this a really exciting time to be bringing books to the screen. Complex narratives are given room to breathe as TV series, which can be consumed as "box- sets" in the same uninterrupted way as films are and simple stories can be expanded into three-dimensional "story worlds" in apps and on virtual reality platforms. Streaming platforms have also created a continuous appetite for new content. Books that already have a proven audience are a logical place to turn to.

How could publishers work better with the TV and film industries?

Coventry: Something interesting is happening: some editors are thinking like producers—looking at the film/TV and publishing industries and working out what people want, as well as trends and new ideas, then finding ways to produce this by teaming up with great writers. It’s a smart way to give people what they want while still creating brilliant books.

Selberg: They could be more aware of what’s happening in the world of the screen and what broadcasters are looking for—reading industry publications and attending conferences like the Children’s Media Conference, or Kidscreen, would help. The big issue is that most publishers do not control the TV/ film/merchandising rights, and therefore it’s not a big priority [for them]. Some rights departments are better than others at pitching to scouts even if they don’t hold the rights, realising that media exposure is good for book sales.

Hayward-Whitlock: I think the key is to keep an open communication up. Publishing announcements and, latterly, sales figures are really useful tools for us when selling titles, so when we have that information readily available, our jobs become easier.

Deakin: From the publisher’s side it’s useful to know the type of films, specials or series ideas that we, as producers, are looking for. When we’re establishing a relationship with a publisher, we find it useful to have fairly regular updates with relevant new titles and stories on their list. Constant dialogue is even more important when you develop a screen adaptation together.

Which adaptations have recently worked particularly well—and why?

Coventry: "Big Little Lies" is the obvious first answer. "Love, Simon" was a beautiful, important and heartwarming example of YA on screen for actual young people—a rare thing. And "Paddington 2" was absolute genius—the most fun I’ve had at the cinema in ages. "The End of the Fucking World" (adapted from Charles Forsman’s graphic novel for Channel 4 and Netflix) is another of my favourites: a brilliantly written, excellently performed adaptation that felt fresh and modern.

Selberg: On the animation side, I think "We’re Going on a Bear Hunt" was a success. It was a faithful translation of the spirit of the book, and well-marketed too. I liked the "Anne of Green Gables" remake on Netflix and it’s clearly been a hit because it is making more. The YA genre is on the rise, especially on Netflix: "13 Reasons Why", "The Kissing Booth" and "To the Boys I’ve Loved Before" are a few examples, but many more have been optioned.

Hayward-Whitlock: "Room" is a really successful example of authors adapting their own work. "Patrick Melrose" pulled off the trick of transferring the strong personality and confessional tone from the novels to the screen. And "A Very English Scandal" is an example of how a book can be a great way into a well-known public story.

Deakin: We’ve been overwhelmed by the reception to "Ethel & Ernest"—a hand-drawn feature based on the autobiographical graphic novel by Raymond Briggs—and "We’re Going on a Bear Hunt", a TV special based on Michael Rosen and Helen Oxenbury’s children’s book. Both were watched by record audiences, on BBC One and Channel 4 respectively.

What are the risks and opportunities in this area?

Coventry: There is always the risk of books being optioned without proper thought, especially when big money is involved. But that tends to happen more in the US. I know lots of authors will have had the experience of their books being optioned and not going anywhere, though that is the nature of the business. I would like to see more niche and experimental work optioned for wider audiences, without the worry of not attracting the right crowd.

Selberg: Brexit is an additional headache. It’s as hard as ever to finance. The BBC is not commissioning much. It’s focused on "fewer, bigger, better", which offers fewer opportunities. There is so much competition out there [for viewers’ time], especially from YouTube. The opportunities lie with the new players in the market, such as Apple, Netflix and Amazon.

Hayward-Whitlock: The risks are the same as with any booming market. There’s a possibility of the market getting oversaturated with material, but there is so much strong material out there and buyers are joining the market all the time—which is also the biggest opportunity. I don’t see a slow-down any time soon.

Deakin: There is a risk that at a certain point all the big, bestselling titles from the past 50 years will have been adapted, sometimes multiple times, and there will not be much room left in the market to adapt and exploit original titles that have not yet had time to build up sales figures and a large international fanbase. As far as opportunities are concerned, there has been a seismic shift, particularly in the past year, in the public’s attitude towards inclusivity—they want the stories they are being told to reflect the diversity of people’s experience. This translates as a great creative opportunity when adapting a book for the screen.

The Bookseller Children's Conference: Camilla Deakin will feature in the session Points of View: What are Producers Looking for, and Why? at 2 p.m. Tobi Coventry, Emily Hayward Whitlock and Ingrid Selberg make up the panel for Full Exploitation: Getting Noticed, Getting Deals at 3 p.m. (both Media Strand). Tickets are available here.