You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

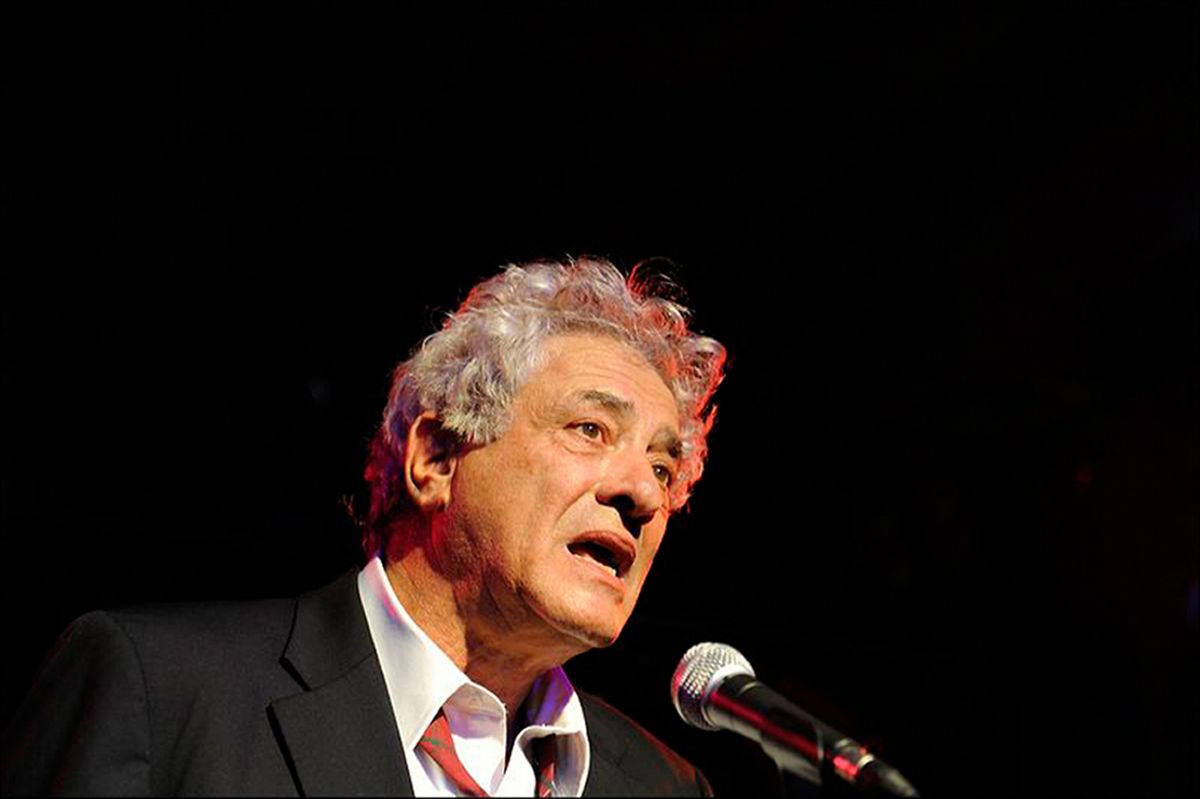

Peter Mayer: obituary

Peter Mayer, who died aged 82 on 11th May 2018, played a larger part in shaping the English-language book world than any other publisher in the past 50 years. He completely transformed Penguin Books, a moribund, loss-making paperback company when he took over as c.e.o. in 1978, and turned it into a huge global conglomerate, the most formidable and admired English-language publisher in the world.

Peter Mayer was born in Hampstead in 1936 to Jewish émigrés; his father Alfred was from Luxembourg, his mother Lee from Germany. They were on a family trip to New York when the Second World War broke out, and never made it back to London. Peter’s extraordinary brilliance revealed itself early. Excelling at school, he won a Ford Foundation scholarship to Columbia University aged just 16, graduating summa cum laude. He spent a year at Oxford, reading PPE at Christ Church, Oxford, and then went to Indiana to study comparative literature, and then as a Fulbright Fellow to the Freie Universität in Berlin to study German literature. Along the

way there were spells as a taxi driver, including a fabled trip when he picked up Allen Ginsberg and drove him to San Francisco to see Lawrence Ferlinghetti; he worked in the merchant marines as an engine wiper, inspired, he always claimed, by Joseph Conrad; as a messenger boy at the New York Times; and for a Madison Avenue advertising agency. As a young man he was head-turningly good looking and worked as a model. He never lost his looks, either.

His publishing career began as an assistant at Orion Press, a US list that has long gone. He then moved to Avon Books, where he arrived as an editor but rapidly rose to be editor-in-chief. When he arrived, there were eight staff. When he left 14 years later, he had made it one of the largest paperback publishers in the US. It was a story he would replicate at Penguin. From Avon, he went briefly to Pocket Books, part of Simon & Schuster, before he was headhunted in 1978 by Lord Blakenham, c.e.o. of Penguin’s owner Pearson, to turn the company around. After Penguin’s founder Allen Lane died in 1970, the company had languished, and by 1978 it was loss-making and stagnant. There were even suggestions that, as a sacred institution like the BBC, it should be nationalised. Peter Mayer did something much more positive. He transformed it into a global cultural force—and an extremely profitable one.

His publishing career began as an assistant at Orion Press, a US list that has long gone. He then moved to Avon Books, where he arrived as an editor but rapidly rose to be editor-in-chief. When he arrived, there were eight staff. When he left 14 years later, he had made it one of the largest paperback publishers in the US. It was a story he would replicate at Penguin. From Avon, he went briefly to Pocket Books, part of Simon & Schuster, before he was headhunted in 1978 by Lord Blakenham, c.e.o. of Penguin’s owner Pearson, to turn the company around. After Penguin’s founder Allen Lane died in 1970, the company had languished, and by 1978 it was loss-making and stagnant. There were even suggestions that, as a sacred institution like the BBC, it should be nationalised. Peter Mayer did something much more positive. He transformed it into a global cultural force—and an extremely profitable one.

At first he faced intense hostility, and not only from the unions which he saw as an obstacle to change. He was seen as brash, a loud American outsider, intent on destroying a venerable institution. Paid a strong six-figure salary, unknown in publishing then, he cut the workforce by up to 20% in short order. More lastingly, he injected American marketing and mass-market ideas into the company. His first big acquisition, The 400, was a flop, but his second, M M Kaye’s The Far Pavilions, was a huge success, selling over half a million copies in six months. It was controversial because he sold it with an un-Penguinlike mass-market cover in untried trade paperback format.

His tastes ranged from the mass-market— he had a brilliant eye for commercial fiction and thrillers—to the rarefied, including much American literary fiction and literature in translation. (Among other achievements, he is credited with creating an international appreciation of Dutch writers). He was, in fact, at home in most cultures: he was trilingual (in English, German and Spanish) and spoke passable Dutch too. He enjoyed the luxury lifestyle of the c.e.o., but was absolutely content slumming it in backpackers’ hostels, cheap dives and roadside cafés as well. Steeped in British and American culture, though adept at playing the outsider in both, he was also a European at heart, and many of his closest friends were Europeans: publishers, agents, writers and journalists.

The Penguin he inherited bought paperback rights from hardback houses, then still largely separate companies. Always a visionary strategist, Peter realised that there was no long-term future in this dependence on other companies and launched Viking to publish "vertically" (hardback and paperback in one house), paying full royalties to authors. It was this move that led to the consolidation of British publishing and the growth of other groups, as hardback companies jostled to ally themselves directly with the paperback reprinters. The next logical step was Peter’s acquisition of Hamish Hamilton and Michael Joseph (Sphere too, though he sold that on) in 1985.

A global pioneer

Peter adored acquiring books and was close personal friends with many agents, including Ed Victor, Deborah Owen and Deborah Rogers. He also enjoyed acquiring companies, buying 11 companies or groups in his 19 years at Penguin. In the UK, Frederick Warne, publisher of Peter Rabbit and friends, was a spectacular success. Early on Peter saw that because the company owned the copyright (Beatrix Potter had married her publisher), the entire revenue and all the rights would belong to Penguin. He created a brilliant global merchandising and licensing programme, of everything from lunchboxes to baby formula. In the US, Penguin, or rather Viking Penguin, had been a modest though very distinguished player until Peter acquired Dutton and NAL in 1986, and then Putnam Berkley in 1996, taking Penguin US into the top three—as it was in the UK. The scale of this change is hard to over-emphasise.

Peter’s interests were always global and he founded or greatly enlarged Penguin companies in Canada, South Africa, New Zealand, Australia and India. Many groups had (indeed have) "branch plants" that distribute global product, but Peter was committed to local publishing to nurture, launch and create local writing and local culture. This was especially transformative in India, where Penguin India was at least 20 years ahead of the competition and pioneered— perhaps even created—English-language trade publishing. Indian literary culture owes a huge debt to Peter. His vision was for Penguin publishing to be both local and global and, as a result, the house was much more deeply embedded in local literary life across the English speaking world than most companies.

Peter’s friendships extended across the world and the professional was also always the personal, which meant he never stopped working. He was no respecter of hierarchies and had friends at every level inside and outside Penguin. A man of boundless, Herculean energy, he worked hard and played hard, normally crossing the Atlantic at least once a month, often more, and endlessly, restlessly travelling the world. As a result he was famous for falling asleep in meetings, films, at the theatre and dinner. He could sleep for 60 seconds or 10 minutes and pick up as if he missed nothing, asking the pertinent question, discussing the play or event. He was also infuriatingly chaotic, endlessly losing keys, wallets, passports and the texts of speeches. He was a heroic risk-taker, professionally and personally, which is why

he had so many accidents. His exuberance, whirlpool energy and charisma palpably changed the atmosphere when he entered a meeting, party, book fair or even a large office. He had an irrepressible twinkle in the eye, a marvellous sense of humour and an unmatched zest for life.

He was a man of intense courage, a quality which was tested thoroughly by Viking’s global publication of Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses in 1988. Looking back, the fatwa on Rushdie and his publishers, the riots in Pakistan, the murder of Rushdie’s Japanese translator, 37 deaths in Turkey and the attempted murder of his Italian and Norwegian translators was an early portent of the horrors of militant Islamism, but no one at Penguin could have known that. Peter exhibited exemplary courage (others involved in the events were less brave) in leading the company from the front, never going into hiding despite the clear danger to his life, and never once budging from his absolute commitment to free speech and the right to publish. As he said: "Once you say you won’t publish a book because someone doesn’t like it, or someone threatens you, you’re finished. Some other group will do the same thing or the same group will do it more."

He showed similar resolve when he agreed to fund the libel case David Irving v Penguin Books and Deborah Lipstadt in 1996, when Penguin went to court rather than concede that David Irving had been libelled by being called a Holocaust denier. Peter could not have known the case would take almost four years to resolve—a triumphant victory for free speech and truth over lies—and cost more than £3m in legal fees.

Peter was tireless and endlessly inventive. His visionary ideas for the Penguin 60s—tiny books sold for 60p to mark Penguin’s 60th anniversary—saw the publisher sell almost 30 million copies of them worldwide, and spawned the later Penguin 70s and 80s. But there was so much else: the switch from A to B format; and Penguin’s constant revitalising and championing of the classics, which he expanded greatly, and far beyond the Western canon. He properly put the Booker Prize on the map when, in 1980, he published five of the six shortlisted titles (though not the winner, William Golding); and he revived Allen Lane’s Penguin Specials and published one of the most successful self-help books of all time, [Audrey Eyton’s] F-Plan Diet. He championed children’s books and revived Puffin, and was constantly alert to the Next Big Thing.

In 1997, after 19 years at the helm, Peter decided to move on—or rather, back. Not content with running the world’s most successful English-language publisher he had, since 1971, also run (first with his father and, after his father’s death, on his own) Overlook Press from Woodstock, New York. A self-consciously independent press, the company published overlooked books. From 1997 this became his full-time passion, acquiring Virginia Woolf’s famed Gerald Duckworth, which he bought out of administration in 2003. His tastes for his own company remained as eclectic as for Penguin, ranging from Sudoku, which he picked up for a song, selling millions of books in the US, to True Grit and Freddy the Pig.

Without Peter Mayer, British, American, indeed English-language publishing would not have taken the form it does. And indeed, the Penguin Random House conglomerate is unimaginable in its present form.

Peter is survived by his daughter Liese (an editor at Bloomsbury US) and his granddaughter Stella; Mary Hall Mayer, mother of Liese; Judith Thurman, a New Yorker writer and long-time partner; and Sophy Thompson, his partner at the time of his death.

There will be memorial services for Peter Mayer in London and New York, details of which will be announced soon.