You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Suzanne Harrington's redemption song

Behind the writing of every memoir of a life gone off the rails is a motive in need of justification. Why bare your soul? Why tell the world just how bad things got? Why, in Suzanne Harrington’s case, would you want to confess that desperate moment—when at your lowest ebb, and already roaring drunk—you scoured the kitchen cupboards for alcohol and ended up gulping down an entire bottle of cold mulled wine left over from Christmas?

“Because I’m a writer,” says Harrington. “This wasn’t a therapy project. It was a writing project. I’d been given a story that was mine to tell. Otherwise I didn’t examine too much why. I just wanted to be completely open about what happened”.

The Liberty Tree is a misery memoir extraordinaire: moving, riveting, beautifully written and profoundly disquieting. At its broken heart, it’s a portrait of the consequences of “deep-frozen” alcoholism. But it’s also an account of drug use, paranoia, being so barking “you’re in Upminster”, surviving cancer, and the break-up of a precarious marriage to the wrong person.

And after all the above, when Harrington had finally gone into recovery and had been sober for seven months, her depressed husband Leo commited suicide, hanging himself from a tree one night on a hill in Brighton.

The Liberty Tree opens with an imagined but unsparing description of his body before its discovery, “stiff and silent and alone in the soft bright morning”. And you find yourself thinking both: why do I need to read this? Then: everyone should read this.

The Liberty Tree is assuredly not a self-help book. But it grew out of a newspaper article Harrington wrote for The Irish Times about talking to children about suicide. On the advice of charity Winston’s Wish, she told her children when they were still very small that their father had taken his own life.

International story

The Irish Times piece caused quite a stir when it published. The day after it ran, the Irish Daily Mail rang up, wanting to use it. Then the Guardian published it, and so did papers in Canada and Australia.

Although she has told them to read it only when they are adults, on account of its sex and drugs content, The Liberty Tree is addressed to Harrington’s two children, now aged 12 and nine. “I started writing it in the third person and it didn’t work. But once I’d had the idea of telling it to them, it just came flying out.”

Once the book was written, Harrington gave it to a friend to read. She in turn passed the manuscript to Becky Thomas of WME. “Becky phoned me up and said: ‘can I be your agent?’ It was like alchemy. Without wanting to sound self-aggrandising, it felt as if I’d managed to create gold from a pile of shit.”

Dedicated to Leo “for all that he gave”, The Liberty Tree is likely to divide opinion. Some will read it as a tragic portrait of addiction, others as a deeply unflattering spewing of a mother’s rampant self-centredness. “The point is that it’s both. Addiction is rampant self-centredness,” counters Harrington, who certainly never reaches for our sympathy. “This is not a self-justification book. I suppose I come across as some kind of monster, whereas in reality I’m not. But my addiction is genetic. I was born without an off button.”

Life is copy

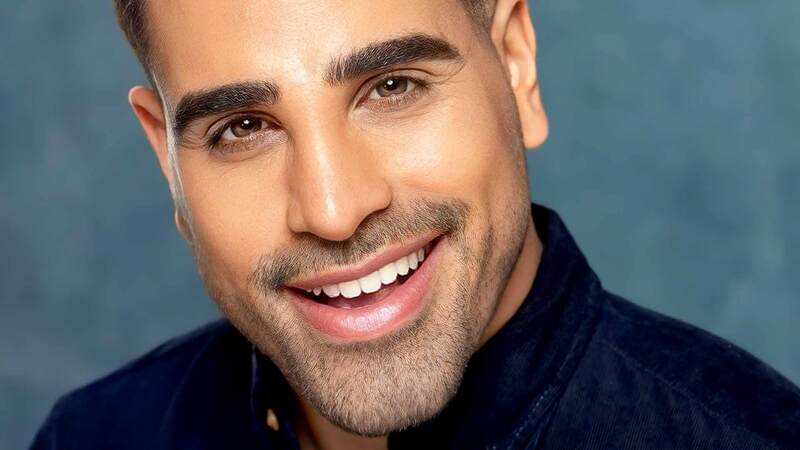

In person, Harrington is warm, direct, and likeable. She also betrays few nerves about what the book’s reception might be.

She says: “I am completely at ease with everything in [the book]. It’s the story of two people who were ill. One had an addiction, the other had depression. Unfortunately my husband’s choice of getting free was a drastic one, and a terribly sad one.”

Does she blame herself? “God, no. That would be corrosive and harmful. I really regret what happened. But Leo died because he was ill, and he was untreated. I’m not powerful enough to make somebody die. None of us are. I wish I’d been able to see the signs.”

The Liberty Tree—the title was inspired by a quote from Seneca—is also a memoir about becoming a mother, and the redemption that children provide. “I think it took until about six months after my husband died before I really started to step up and bond properly with my kids,” she says. “That sounds awful. But it’s completely normal if you’re an addict. It’s not that you don’t love your children, but it’s as if you are behind a glass wall.”

Harrington is now working on a prequel to The Liberty Tree; a memoir of her time “chasing her tail around the world”, living in different countries. “Nora Ephron said ‘life is copy’. It sounds cold-hearted to say that when bad things happen, but it is. It’s what forms you, and it’s what informs you.”

The Liberty Tree by Suzanne Harrington is published by Atlantic.