You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Teachable moments? Why increased funding is key for the schools sector

With election campaigns heating up, education publishers are urging more money for cash-strapped schools and a government willing to tackle the thorny issues

Trade professionals in the schools sector are not overly enthused by education policies being floated by the political parties ahead of next month’s general election, though many are guardedly optimistic about the trial balloons from the manifestos. Yet universally, British publishers and librarians stress the desperate need for an increase in funding for schools across the board, particularly in teacher recruitment and retainment.

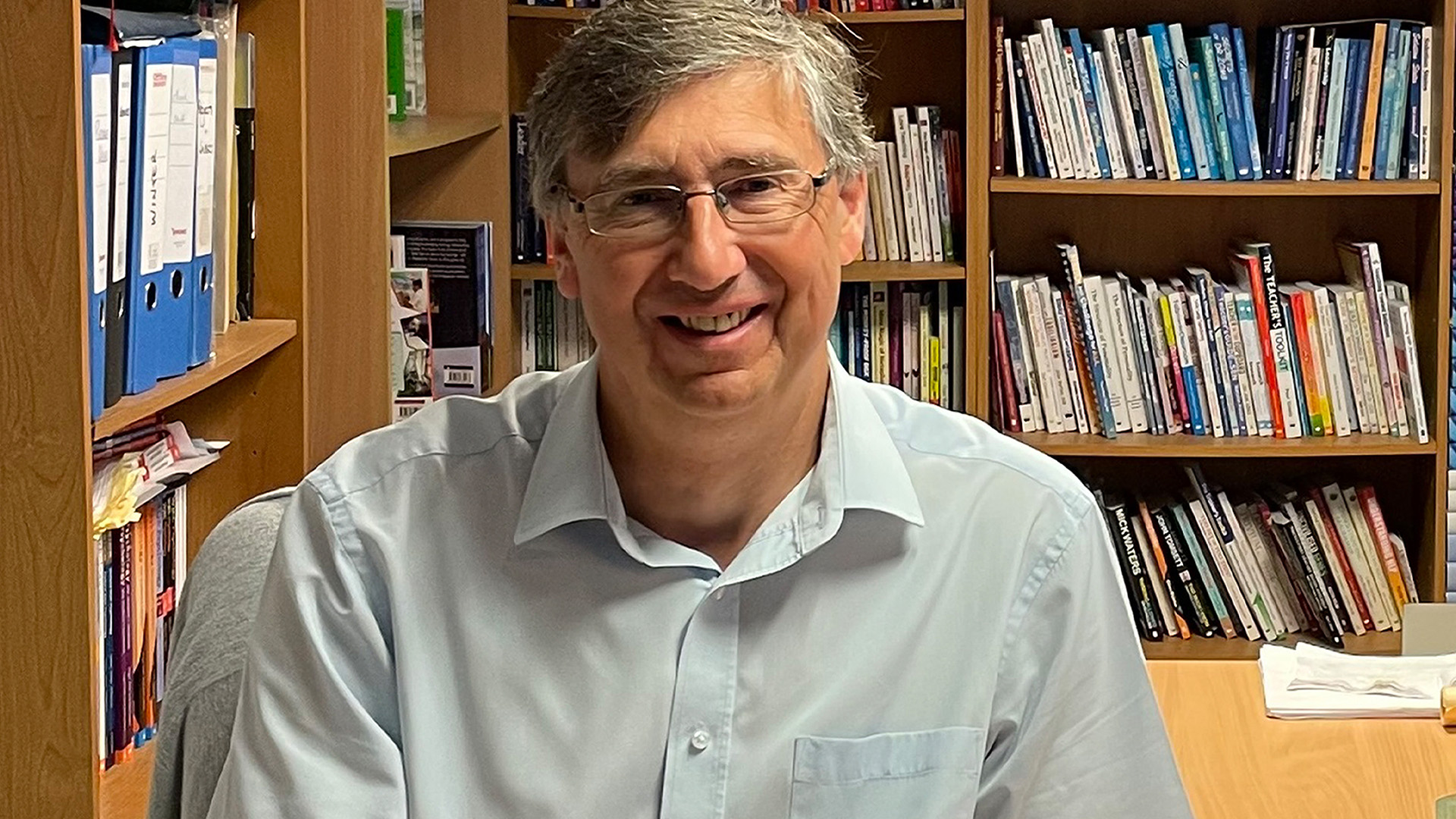

Lee Newman, Collins’ publisher for education and the chair of the Publishers Association’s Education Publishers Council, says: “It won’t surprise you that the main thing PA members are looking for is an increase in funding, as there has been no real-terms growth in school spending per pupil for 14 years. Schools simply need more money: they are grappling with rising costs, there’s obviously a recruitment crisis. SEND [Special Educational Needs and Disability] requirements are far outstripping system capacity.

“Plus, schools are still trying to catch up after the pandemic, which has disproportionately affected different learner groups. So an injection of funding would be really useful. We know that quality-first teaching is the most effective intervention to boost learning, and brilliant teaching and learning resources will support them in delivering that quality-first teaching.”

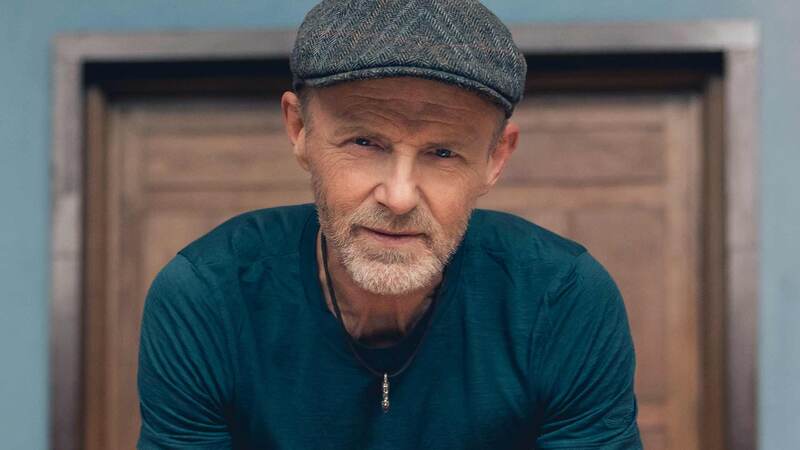

David Bowman, m.d and co-founder of Wales-based teacher development specialist independent Crown House Publishing, echoes Newman’s point: “Schools are very stretched financially… We need to invest in professional development and reduce workload—numerous research studies have shown that the most important factor influencing student achievement is the quality of teaching. The recruitment and, particularly, retention of the best teachers should be the number-one priority. This means increasing salaries, focusing on professional development and reforming the punitive accountability system.”

Wanting a boost in schools coffers is not merely high-mindedness; there is a hard business case for publishers. The PA’s most recent annual statistics round-up, Publishing in 2023, shows the UK domestic education conditions challenging, with revenues dipping 12% (on invoiced sales) to £192m. This, of course, is still a gain on the very rocky pandemic years of 2020 and 2021—£144m and £158m, respectively—but contrast it to 2016 and 2017, when the home-market schools revenues were at £220m and £200m.

And while the British education system is in difficulty at home, its cachet across the world has never been better: UK publishers’ export sales rose 7% last year to a near-record £469m. This is an irony not lost on Newman: “In lots of markets, British curriculum resources are still seen as the gold standard. So that plays back into the PA wanting to support the education publishing industry for our domestic markets, because that can also help the export potential.”

Continues...

The school-library sector has been hard hit during this difficult funding period, with as many as one in seven schools across the country now without a dedicated library space. The School Library Association (SLA) c.e.o. Alison Tarrant says the landscape for her members is mixed: many school libraries that are supported are doing great work, though there has been a reduction of school libraries and without any school-library staff the issues this creates are significant.

She adds: “But even our members—who you might assume would be more engaged and supported—are facing real struggles. Our member survey this year highlighted challenges from reduced budgets and space to reduced attention spans in pupils. There is also a disconnect apparent between school-library staff and their teachers/senior leaders, with many reporting struggles getting teacher buy-in or being overlooked or ignored by their senior leaders.”

‘There seems to be a recognition [among some political parties] of the importance of creativity for the future world of work—and school libraries are supporting this in all kinds of ways’ – Alison Tarrant

Tarrant and the SLA’s main policy wish has not been flagged by any of the party’s manifestos: “Given the economic and political landscape, I wasn’t expecting—though am always hoping for—a headline promise about school libraries for every child. But there are elements in the manifestos that school libraries can help be the answer to, whether that’s oracy, digital skills, literacy, a broad curriculum, increased after-school offerings and supporting well-being.”

In the end, Tarrant feels there are “elements of a few [of the manifestos] that have potential to be positive. There seems to be a recognition of the importance of creativity for the future world of work—and school libraries are currently supporting this in all kinds of ways”.

Continues...

Manifestos can promise the moon, but often run up against the harsh reality of how to come up with the funds. One of the key education planks for Labour—which, unless Keir Starmer emulates a Neil-Kinnock-in-1992-nose-dive, will almost certainly be in power come 5th July—is the recruitment of 6,500 new teachers, along with increased training for teachers and headteachers. But that is costed by its proposed introduction of VAT on private schools, and whether the £1.5bn Labour says the government will theoretically earn by the time the new tax happens in practice remains to be seen.

Bowman is generally cheered by many education policies put forward by Labour, and the Liberal Democrats, but he cautions that they need to reflect what’s happening at the coal face. He says: “The recruitment of 6,500 new teachers is promising, but without making the profession more attractive in terms of pay, conditions and reforming the accountability culture, I fear these won’t be long-term appointments.”

And election pledges do not often address the finer detail of pressing issues. One of the big points of contention in the sector is around Oak National Academy, an online school set up during the onset of the pandemic to provide free resources for teachers. In 2022 it was established as an arm’s-length public body by the Department for Education, receiving £45m in public funds. Last November, the PA, British Educational Suppliers Association and the Society of Authors were granted a judicial review of the Oak National Academy’s status by the High Court, with their filing saying Oak currently “risks causing irreparable damage to the school sector as we know it… no existing provider can compete fairly with [it], and [it] will undo decades of work by publishers, tech innovators and others whose expert workforce have created our existing rich range of world-leading resources for schoolchildren across the country”.

The review is still rolling on. Labour education shadow ministers have publicly remained mum on Oak National Academy, but Newman asserts that the issue must be dealt with: “It was a fantastic initiative during the pandemic. When schools were closed, lots of education publishers donated resources to Oak. But I don’t think there’s a justification to continue investing in it as it is now. We’re looking for a reduced scope for Oak so that it’s a more effective and sustainable use of public funds that respects teacher choice. We believe they are best placed to evaluate different curriculum models and tailor their teaching to meet the needs of their schools and learners.”

David Bowman on what the manifestos miss

“Although they touch on it, there is no debate about what we should teach in schools. And this is not a new phenomenon. Under [former education minister] Michael Gove there was a major shift towards a more knowledge-based curriculum and more rigorous exams. This had led to lower emphasis being given to skills and critical and creative thinking. The current system is designed to cram knowledge into children so that they can regurgitate it in exams. There is a long-standing debate between traditionalists, who are holding sway at the moment, and progressives, who argue that skills and producing well-rounded and confident learners are more important. It is of course a false dichotomy, and we need both knowledge and skills. The World Economic Forum’s most recent desired workplace skills include analytical thinking and innovation, active learning and learning strategies, complex problem-solving, critical thinking and analysis, creativity, originality and initiative, leadership and social influence, technology use, monitoring and control, technology design and programming, resilience, stress tolerance and flexibility, reasoning, problem-solving and ideation. Very few of these are taught explicitly in schools.”