You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Translated fiction soars after Booker rule change in 2016

The switch for the International Booker Prize, which is now awarded for a single title rather than a full oeuvre, has seen translated titles’ sales soar in the UK.

While the main Booker Prize’s post-win bounce has been long celebrated, the organisation’s sister international award—the shortlist of which will be revealed at today’s London Book Fair—can have an effect on book sales which is similarly profound.

Sure, the overall units won’t be as gaudy, but on a percentage basis it can be almost as eye-popping. The 2021 main Booker champ, Damon Galgut’s The Promise (Chatto), shifted 1,537 units through Nielsen BookScan’s Total Consumer Market in the month prior to its win; in the four-week period after the prize it moved 25,572 copies, a percentage rise of 1,563%. And, of course, a Booker is transformational in the long-term for an author. Heck, even in the short-term: Galgut shifted more books in the 12 weeks after winning the Booker (just over 81,000 copies) than he did in the previous 17 years since first being published in the UK.

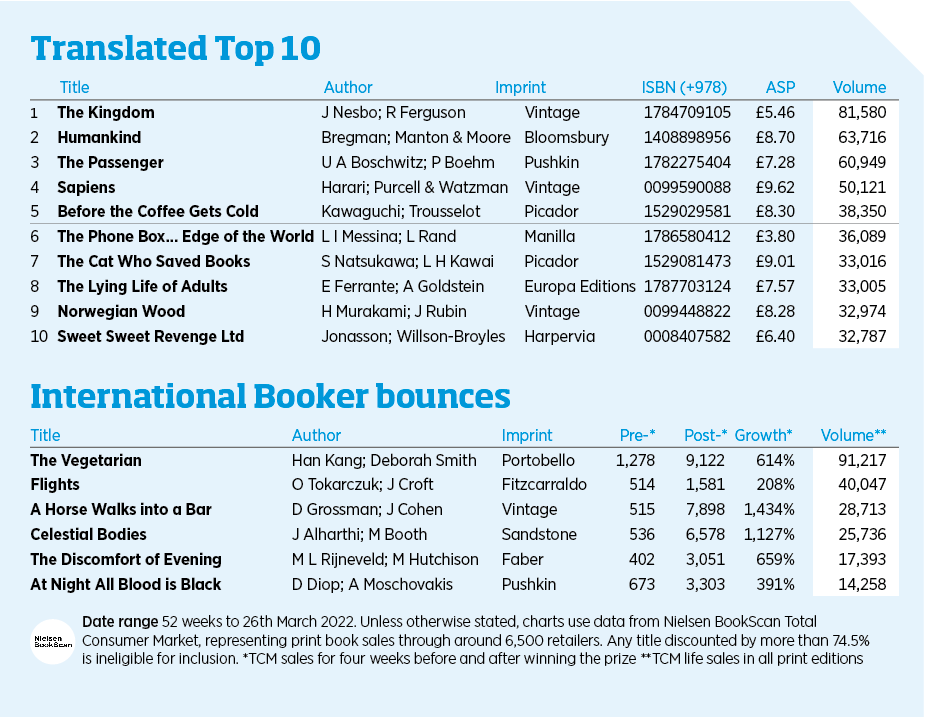

That Galgut post-win boost is almost matched in percentage terms by two of the books that have won the International Booker Prize since the award was changed in 2016, moving from a full-career gong to its current, single title in English translation model. The 2017 champ, David Grossman’s A Horse Walks into a Bar (Vintage, translated by Jessica Cohen), jumped by a whopping 1,434% in the first month after its win, while 2019’s Celestial Bodies by the Omani writer Jokha Alharthi (Sandstone Press, translated by Marilyn Booth) also rocketed by more than 1,000%.

Yet the two titles got there by different means. The great Israeli writer Grossman had arguably the biggest profile of any of the post-2016 winners (at the time of shortlisting, that is; now Nobel laureate Olga Tokarczuk has undoubtedly surpassed him). Profile in the translated literary fiction space is somewhat relative; Grossman’s biggest seller through the TCM pre-2017 was 2010’s To the End of the Land, which had sold 12,000 copies in all editions. But the massive percentage jump post-win is down to Vintage taking a punt and timing the release of the A Horse Walks into a Bar paperback with the prize’s ceremony. It paid off: Grossman’s eight biggest weekly sales hauls have occurred in the two months after his win.

Alharthi’s massive boost is due to a common denominator among International Booker short- and longlistees: it was coming from a very low base. No shade to Alharthi or publisher Sandstone: a first novel translated into English by a little-known writer—incidentally, Alharthi was the first Omani female novelist to ever be translated into English—set in rural Oman is not what you would call an easy sell. In fact, only once in its first eight months after publication (in June 2018) did Celestial Bodies exceed a single-digit weekly unit-sale through BookScan (in the week ending 18th August 2018, when it sold 24 copies). It did not crest the 100 units per week mark until it was shortlisted for the prize.

It is perhaps telling about the state of literary translation in the UK that four of the five International Booker winners come from gutsy indies like Sandstone and Fitzcarraldo Editions, which are doing much to push boundaries and cross borders. That such indies end up winning the overall crown is not an aberration; only three of the 13 longlisted titles this year are published by conglomerates.

One of the translation trends of the past half-decade or so is an openness to publish more non-fiction

But it would be unfair to suggest those conglomerates are not contributing to getting translated titles into the UK market, they are just arguably focusing on more commercial fare. Eight of the top 10 books in translation over the past 12 months come from the big boys, led by Jo Nesbo’s The Kingdom (Vintage, translated by Robert Ferguson). In the past year, the Harry Hole creator’s all-time TCM total moved to just a smidge under £25m, to edge past Paulo Coelho as the second-bestselling author in translation since BookScan records began. It might be a while before Nesbo can catch the late Stieg Larsson, who, at £34.7m, is the all-time translation pace-setter.

One of the translation trends of the past half-decade or so is an openness to publish more non-fiction. Previously the bulk of non-fiction in translation was classics like Anne Frank’s The Diary of a Young Girl or titles ostensibly kept in print for historical purposes, such as Hitler’s Mein Kampf, which has sold £1.8m in the BookScan era, 90% of which is through Penguin Random House editions—the proceeds of which the publisher says it donates to anti-discrimination charities. Then there are the somewhat odd, out-of-nowhere hits: remember Frenchman Pierre Dukan’s The Dukan Diet titles from the early 2010s? The “no treats, no fruit, no carbs, no alcohol” books (one doubts Dr Dukan was really French...) earned nearly £4m through the TCM.

There has also been serious translated non-fiction brand building of late, such as Italian physicist Carlo Rovelli and two of this year’s top 10, the Dutch historian Rutger Bregman and Yuval Noah Harari. Although Harari is perhaps a debatable inclusion in this top 10, given he translated Sapiens (Vintage) himself “with the help” of John Purcell and Haim Watzman.

Japan is clearly the hottest territory at the moment. First, the huge explosion of Manga—driven in large part by Waterstones whole-heartedly embracing the genre—saw Hajime Isayama and Kōhei Horikoshi become the top two authors in translation last year. Meanwhile, long-time translation superstar Haruki Murakami features prominently with his classic Norwegian Wood (Vintage, translated by Jay Rubin) in the top 10, while he earned just over £1m last year, to bring his all-time TCM haul to £19.5m.

Two Picador titles join Murakami in the top 10 and they are both life-affirming fantasy fables based in shops: Sosuke Natsukawa’s The Cat Who Saved Books (translated by Louise Heal Kawai) is about a talking cat in a second-hand bookshop, while Toshikazu Kawaguchi’s Before the Coffee Gets Cold (translated by Geoffrey Trousselot) is set in a cafe where customers are given a chance to travel back in time to fix things in their past. Another Picador title by a Japanese author is 2022 International Booker-longlisted, but is far grittier: Mieko Kawakami’s Heaven (translated by Greg Bett) centres around a 14-year-old who is subjected to horrific bullying.

Lastly, though it is translated from the Italian by Lucy Rand, The Phone Box at the End of the World is set in Japan and written by Laura Imai Messina, who emigrated from her native Rome to Tokyo in 2006. Though Messina has an outsider’s perspective, the novel’s themes jibe with the quirky, magic-realist bent of the two Picador books in the top 10: the phone line to the titular box has long been discontinued but for years the bereaved have gone to it to “talk” with their dearly departed. Grief-stricken Yui, who has lost her mother and daughter in a tsunami, arrives and there meets widower Takeshi. Will the two find solace with each other? You know, I think they just might...

The Bookseller will publish its Translation Focus on 25th May. Those with features or interview pitches can contact managing editor Tom Tivnan (tom.tivnan@thebookseller.com).