You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Adeola and Wilson-Max call for trade transparency on race

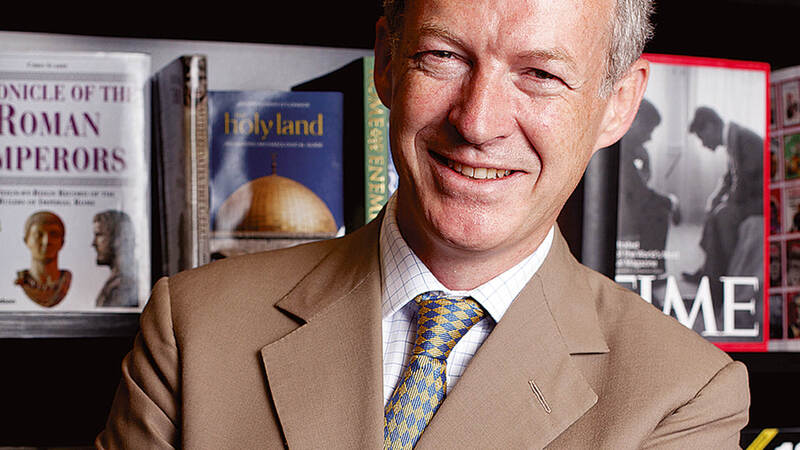

Illustrators Dapo Adeola (pictured) and Ken Wilson-Max have said the industry could be on the cusp of change over diversity but it requires more black people in sales teams and greater transparency on race.

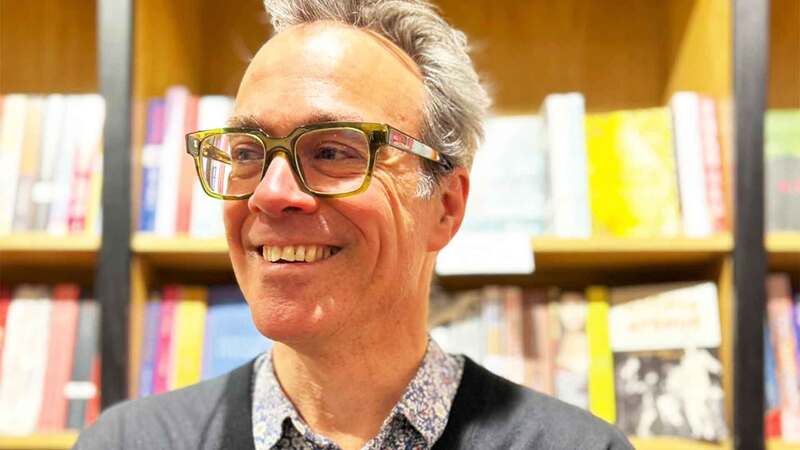

The artists, two of just four black British illustrators currently working in children's publishing, had a wide-ranging discussion on Instagram Live about their experiences coming through the industry.

For Wilson-Max, the journey began in 1987 and has seen him illustrate 70 books and set up his own indie Alanna Max, while Adeola only came into publishing two years ago but has already found success on titles such as Look Up! (Puffin) with Nathan Bryon.

Adeola said entering the industry had been a “lonely” experience and he had been actively trying to find other black illustrators coming through to support them.

But the pair said they hoped the industry might finally be on the cusp of actual change after repeated discussions about diversity and the issue coming to the fore again in recent weeks.

Adeola said: “After all this talk, and I've only been here for two years... I feel like the industry is about to start really listening.”

But he continued: “I feel like the people tasked with making the change still lack experience in terms of knowledge of the communities that they want to represent and it's this weird thing that I find that nobody talks to the people that they want to represent. I've had a conversation with a few people that are in this chat right now who are listening to us about this, authors, and they work with these publishers and the publishers don't ask them what's going on, how are you, what can we do as a publisher to make your experience better, how can we improve, how can we be more diverse.

"They never ask the talent....You claim to want to be doing this in our best interests yet you don't know what our best interests are because you don't want to ask.”

Adeola said Macmillan Children's Books was the first publisher to sit down and have that conversation, leading to an event with the press supporting black British illustrators last year. He said asking those questions showed firms were trying to learn and were far preferable to a very white industry trying to dodge the issue of race completely.

He said: “If we address it head on and we're like 'we know this is a predominantly white industry, how do you feel as a black person in this industry, what can we do to make you feel comfortable', I would take that as a good sign coming from my publisher.”

The pair said sales people and buyers were mostly from the same demographic which led them to discount the potential of titles because they didn't understand the books. Instead, they were stuck looking at the same old trends.

Wilson-Max recalled how, at the Bologna Book Fair one year, a Scandinavian publisher took one look at the cover of his book and said it wouldn't sell because there was a black child on the cover.

He said: “I think we do have a problem, on the page, off the page. I think it's being addressed in slow, steady ways because there's not enough feedback to make it go faster.

“I think you need to have people taking chances on the publishing side and then people taking chances on the innovation side as well. I think we need more sales people that can see a new market.”

Adeola agreed: “We need more diversity in the sales teams, we need more diversity amongst the gatekeepers, amongst the purse-string holders.”

He said everyone he had worked with in the industry had been “fantastic” but it was the ones that called the shots that “can't seem to get it right”.

And he added: “Black books aren't just made for black people. They're made for people. So the thinking that, because we're making a black book it has to be targeted at a black demographic, that's nonsense to begin with.”