You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

‘Children need more inclusive books’

Inclusivity in children’s literature is improving but there is still a lot of progress to be made in order to reflect modern realities for young readers, trade figures have said.

The Reflecting Realities: British Values in Children’s Literature conference was held by the Centre for Literacy in Primary Education (CLPE) in Southwark, south London on Wednesday 1st March.

Kerry Mason, co-director of inclusive children’s book supplier Letterbox Library, said: “There are definitely more inclusive children’s books now than there were 10 years ago, but there are still not a great deal of them and most stories are still led by a white boy.”

She added: “There is a misunderstanding of what we mean about diversity. It’s not about having books on issues like sexism and racism, it’s about having different types of people represented in books.”

Children’s author Catherine Johnson, who ran a workshop at the event, told The Bookseller: “It is still easier to buy a book with a dragon on the cover than it is to find one with a black child. Although it’s good to see a wider range of YA books with LGBT [lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender] characters now, there is still a dearth of books with protagonists of different classes, abilities or races.”

Empathy Lab founder Miranda McKearney spoke about founding the organisation, which promotes the power of stories to build empathy, echoed this. “It feels like the industry has made good progress in some areas, but there’s such a long way to go in others. It’s especially hard to find a wide range of books for primary school children that reflect the multicultural nature of the UK population”.

Letterbox Library co-director Fen Coles told The Bookseller: “Sometimes there’s a peak in a particular area of representation, but we don’t sustain that and talk of an ‘explosion’ of inclusive publishing sometimes amounts to a handful of books. We need to do better.”

This year’s Carnegie Medal longlist, which does not include any writers of colour, was cited as an example of how far the book trade has yet to go in terms of representation.

These concerns have prompted CILIP to announce strategies around its Equality & Diversity Action Plan, which include holding an independently chaired review of the CILIP Carnegie and Kate Greenaway Medals for the 2018 prize onwards and looking at how diversity, equality and inclusion can best be championed and embedded into its work.

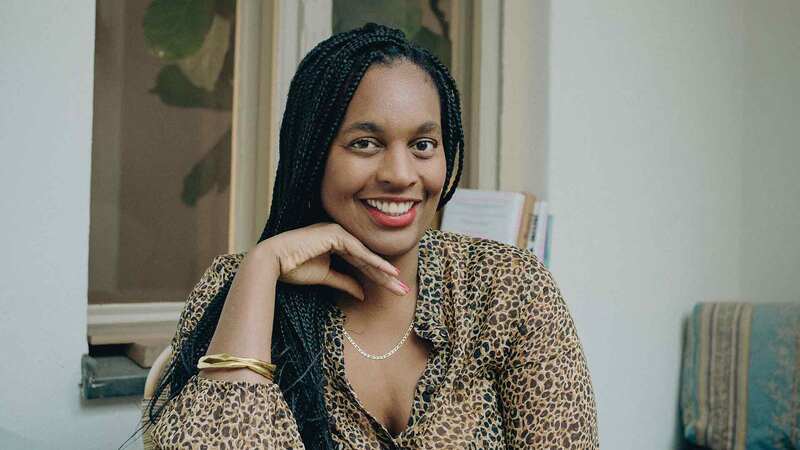

(l-r) Farrah Serroukh introduces a discussion between Firetree Books founder Verna Wilkins, Fen Coles and Kerry Mason. Credit: Michael Thorne

Mainstream

It was also suggested that publishers’ risk-aversion (owing mainly to financial constraints) has limited the publication and promotion of inclusive books. “When the publishing industry feels threatened, they stick to tried and tested classics to stay afloat, which aren’t always inclusion-friendly,” said Coles.

Farrah Serroukh, learning programme leader at CLPE, told The Bookseller: “Publishers are more inclined to back writers, themes and realities they perceive are most likely to sell to the mainstream, without appreciating how much their choices shape what becomes mainstream. This underestimates the audience and robs all readers of the opportunity to be valued and to broaden their perspectives.”

Johnson praised publishers for casting their nets wider to find new writers with initiatives such as WriteNow from Penguin Random House and Stripes Publishing’s BAME [black, Asian and minority ethnic] young adult anthology, but warned that it was still hard for writers to sustain a career. She said: “We’re in a better place than three years ago, but I can easily see things getting worse as there is less money around, and publishers and consumers are less keen to take risks.”

Moving forward

In terms of taking steps to make children’s literature more inclusive, Louise John-Shepherds, chief executive of CLPE, urged school teachers and librarians in the audience to create the demand for more inclusive books.

Coles told The Bookseller: “I would like the industry to be more confident about the inclusive books it produces. People can’t get access to the books that exist. These are just good stories and should be sold and marketed as such.”

Johnson called for the publication of new writers, and the promotion of existing minority authors. McKearney advocated stronger connections with libraries in devising new initiatives, support for Inclusive Mind’s Everybody In Charter, which promotes inclusivity, and connecting more children with existing diverse writers. Serroukh called for “books that feature ‘otherness’ without it being a defining feature”.

Serroukh also challenged the use of the word ‘diversity’, saying: “It’s not about diversifying; it’s about normalising all realities.”