You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Events asking authors to work for free 'holding back diversity of voices'

Too many events still ask authors to work for free or do not disclose payment fees clearly at the outset, harming efforts to diversify panels and festivals, according to trade figures.

Many in the industry have also highlighted the need for access costs covering travel, accommodation and childcare at live events to ensure a range of voices can be heard. There are also calls to keep hybrid and digital events, providing more options for disabled writers and writers from remote communities.

Agent Juliet Pickering recently highlighted on Twitter the need to pay authors who speak at events. She told The Bookseller that only a few invitations “make clear from the outset that there is a fee, what that fee is, and whether additional expenses are covered”.

She said that while organisations such as the Society of Authors publish observed rates and link to useful resources as guidelines, she would welcome a “more distinct and transparent system [which values] authors’ time and expertise without question”. She cited the Live Literature Fee published by the Scottish Book Trust, which is £175 per session. Although the trust stresses this is not a recommended fee, it recognises that many authors and organisations in Scotland use it as a benchmark.

“Not only do authors and agents often have to chase down a fee, but the time an author needs to prepare, travel to and wind down from an event is often not considered,” said Pickering. “For some authors, events can be a challenge to their mental health, and for event organisers to be clear, concise and empathic from the outset would be so helpful. Some are, and I really appreciate it, but it should be the norm that an author is told from the first approach what they will be paid.

“The days of ‘this is free publicity!’ should be well over, especially at a time when author income is more stretched than ever before. Events can be an important and vital source of income to writers, and we should pay them fairly.”

Nicola Solomon, chief executive of the SoA, who last week helped launch the Pay the Creator campaign from the Creators’ Rights Alliance, agreed. She said authors should ask from the outset what the fee is, if expenses can be paid, as well as any access costs for things like childcare and accommodation, and if the event covers insurance.

She pointed to guidance on rates and fees outlined on the SoA’s website and recommended writers use Andrew Bibby’s Ready Reckoner to find a salary equivalent for their expertise and convert it into a freelance day rate. While this rate is “probably well above” what writers are likely to be paid, it gives them a “good base to negotiate”. She also stressed the need for writers to check if an event can pay their VAT on top.

Heather Parry, SoA senior policy and liaison manager for Scotland, stressed negotiating a fee is also important for diversity.

One example of equal payment is Natasha Carthew’s The Working Class Writers Festival. “We pay artists the same, we pay for travel, we pay for hotels, we offer childcare if people need childcare. It’s quite a simple model really but loads of festivals certainly don’t offer it upfront and that hasn’t changed and I think that’s a real shame,” she said.

“When you’re applying for funding as a festival you know how much you’re going to be paying everyone, you know how much it’s going to cost, so those festivals often have the money put aside but they still don’t offer it up.”

By keeping payments hidden, events end up with the “same writers rocking up at the same events because they can afford to go,” Carthew said. “They don’t have to take a day off work because they don’t have another job, they can pay someone to do childcare.”

Key to being able to offer writers a fee, as well as any extra expenses and access costs, is applying for funding. In Scotland, Creative Access is the main distributor of funding from the Scottish government and the National Lottery to support arts and culture. Literature officer Viccy Adams said one of the things the organisation looks for in any funding application is “where the principles of fair work are… so that writers and other literary professionals are being paid a fair industry rate”.

“If somebody is being asked to do a professional job or a professional appearance or workshop and there’s no fee, that’s really problematic, and that would often be a reason to not fund something or to go back and have a conversation with people about withdrawing their application and resubmitting it,” she said.

“It’s just one of the basic things we would expect. And on top of that, travel costs and accommodation, where relevant. And we encourage the festivals that apply to us for funding to think through what access costs they might need. I think a fairly classic example might be around hosting a disabled writer. That writer might need a taxi rather than being expected to get a bus from a train station, for example. Or they might be more comfortable travelling in their own car or need to bring a carer with them. Or rather than a standard one night’s accommodation, they might need two or three nights because they have an energy-limiting condition.”

She added: “Programme and festival organisers are really keen to be able to provide that kind of support but may end up making budget-led programme decisions that exclude a lot of interesting and fascinating voices.

“That’s the kind of situation where support from public funds can make a real difference in being able to meet those higher costs so there’s a slightly more level playing field for the people involved.”

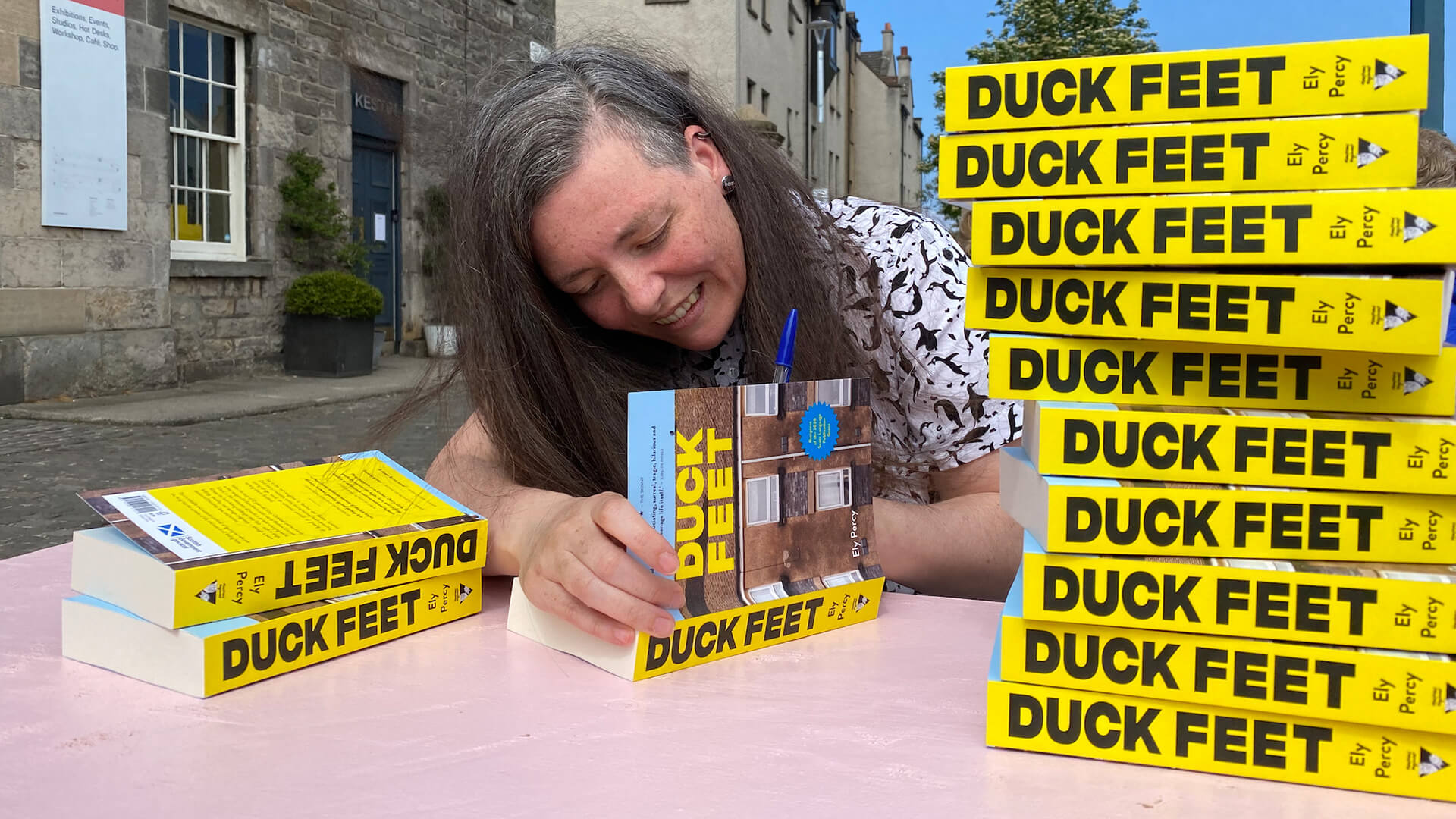

Author Ely Percy said things have been “phenomenally different” in the past eight to nine months over things like travel expenses, accommodation and access needs. They said: “I don’t know if this because of the success of my second novel or if access has improved because of the pandemic or something else. It’s probably a mixture.” However, they noted that many writing fellowships still remain inaccessible, as there is “almost never any provision to have a carer”.

Fellow writer Helen Sedgwick, who lives in the Highlands and is chronically ill, said she was only able to apply for, and win, this year’s Dr Gavin Wallace fellowship for mid-career and established writers to develop creative work during a year-long residency, because it was open remotely during the pandemic. “I always thought it looked incredible and wanted to do it and also thought that it was just out of reach for all these reasons of accessibility and childcare and illness. Creative Scotland announced this remote fellowship and I suddenly thought I can apply, it’s possible,” she said.

She thinks things are getting better and the pandemic, alongside the pivot to hybrid, has changed the way people are thinking about events. There are now also more groups advocating for change such as Inklusion, which is producing a guide for making literature events accessible for disabled people.

Julie Farrell, Inklusion co-founder, told The Bookseller she never accepts anything unless it is paid and she pushes for access costs. “We fully expect that someone will pay for our travel, pay for a hotel room for us to lie down in or stay the night, if needs be, and that does extend out to people who have children or care responsibilities. There has to be some kind of financial contribution to helping somebody in order for them to participate in the event.”

She also warned against access which is “tokenistic”. “People want to be seen as doing the right thing, but it actually takes consistency, persistence and the dismantling of the systemic issues” she said.

Jeda Pearl Lewis, co-director of the Scottish BPOC Writers’ Network, said it was difficult to find information on appropriate access costs before Inklusion, and said she was excited to see the guide. Despite its small size, the network is committed to “baking in access requirements into each programming strand” covering everything from travel bursaries to childcare and respite care.

She said organisers “must be respectful of people’s time”, particularly when asking people to work for free. “Even if you think you’ve got a really good reason, you’re asking someone to volunteer if you’re not paying them, and you have to say it’s voluntary work and this is why I’m asking you to volunteer. There are obviously situations where artists will quite happily do so but it needs to be more of a choice than an expectation. The standard should be that you will be paid.”

This is something the SoA’s Solomon agreed with: “I always say to people, it’s fine to do things for free but make sure you value what you do. So if you’re doing something for free, work out why you are, is it going to give you profit, is it going to give you pleasure, and is it going to give you publicity? If it isn’t going to give you one of those, or if it’s not worth it for you, don’t do it.”