You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Men dominate trade’s senior positions, data shows

The book trade has wrestled with its gender pay gap revelations this week, with the overall trend emerging that despite women forming more of the workforce in companies across the sector, it is men who dominate the most senior positions and attract the highest pay and bonuses.

The findings have come after a new government ruling required companies with more than 250 employees to publish their gender pay gap data by Wednesday 4th April or face fines, with 19 firms in the book sector, across trade publishers, retailers and academic presses, reporting figures.

Following the revelations, Lis Tribe, president of the Publishers Association and group managing director of Hodder Education, welcomed the initiative for prompting "honest and helpful" conversations. "The evidence provided by this audit is rough, but it paints a picture we cannot ignore. It is the best we currently have, and it provides a starting point for action," she said.

The data, taken from a "snapshot" of salaries on 5th April 2017, is not designed to uncover unequal pay between the sexes for equal work, which is illegal, but to shine a light on when and where men on average reach higher-paid positions than women. As such, companies are obliged to reveal the average hourly median and mean pay differences between men and women as a percentage figure, along with the same split for bonuses. Firms were also required to split their operations into four quartiles and report the gender balance in each, in order to identify disparities in roles more likely to be higher- or lower-paid.

The national average gender pay gap (for full and part-time workers) is 18.4% for median earnings and 17.4% for mean earnings, according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS), which uses the median measure to define the gender gap. The median is the figure that falls in the middle of all employees’ salaries from lowest to highest paid, while the mean figure is calculated by dividing the total wages of a company by its number of staff.

The statistics show that from the 19 companies to have reported gender pay gap data from the book trade, women make up an average of 59.17% of the sector’s workforce, but men dominate the top pay quartile and are paid the highest bonuses, on average.

A breakdown by sector

The data varies between companies. Elsevier reported the highest median gender pay gap from across the book trade, at 40.4%—more than double the national average. Its mean hourly rate was also far above the national average, at 29.1%.

The second-highest median figure in the academic sector was posted by Wiley, which had a pay gap of 21.5% (mean: 21.1%), followed by Cambridge University Press’ on 19% (mean: 24%). Pearson as a group recorded a median gap of 15% (mean: 21%), slightly lower than Springer Nature’s figure of 15.2% (its mean was 17.61%), while Sage came in at a median of 14.5%, with a mean of 22%. Oxford University Press filed a median of 12.6% and a mean of 24.1%. Taylor & Francis ranked the lowest of the academic publishers in median terms, reporting a pay gap of 8%, although it had a mean of 24.2%, higher than the national average.

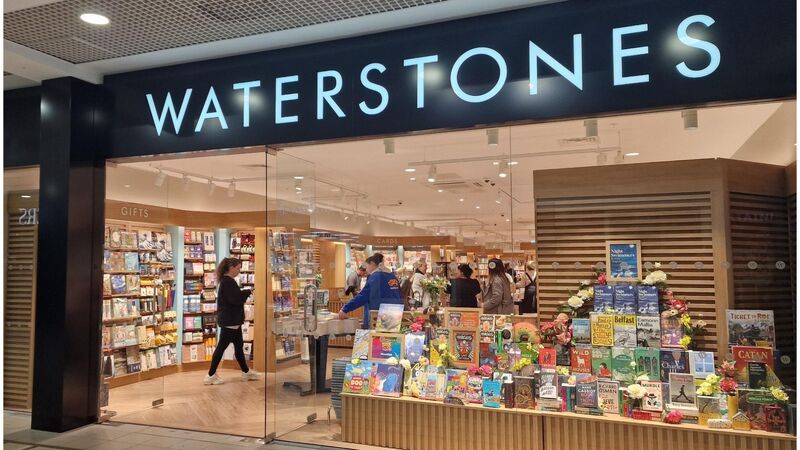

Figures from retailers revealed less of a gap. Waterstones revealed an overall median gender pay gap of 4.5% (mean 13.9%), which is below the national average, while Blackwell’s’ was 1.8% (mean 11.5%). W H Smith, Amazon and wholesaler Gardners reported negligible median gender pay gaps at 0%, 0.7% and 0.1% respectively (means of 20.6%, 6.1% and 3.2%). That said, despite W H Smith’s workforce being 65% female, women make up 27% of its senior management team, and a third of its board are women—a state of affairs reflected in its bonus gender pay gap, which was 51% (median) and 87.9% (mean). Likewise, the difference in what Waterstones pays men and women in bonuses is striking, with a median difference of 25% and mean of 91.6%, which the company attributed to bonus payments made to board directors.

Among the trade publishers, Bloomsbury revealed an overall median gender pay gap of 17.2% and a mean of 23.3%; HarperCollins recorded a gender pay gap of 10.4% (median); and children’s publisher Scholastic’s was 8.4% (median) and 15.1% (mean). Meanwhile two of trade’s biggest players—Hachette UK Group and Penguin Random House UK—both reported a median hourly rate marginally in favour of women, at –1.32% and –1.6%, respectively. For the Hachette UK Ltd legal entity though, which does not include its warehouse operation, the median pay gap is much higher (24.71%), while the mean was higher still (29.69%). Macmillan Publishing International Ltd (MPIL), which comprises Pan Macmillan, Priddy Books and Macmillan Distribution (MDL), bucked the wider trend with its median pay for women 34% higher than men, and with a mean average of 2% in favour of women.

What’s going on?

As Tribe cautions, in this first year of reporting, the headline gender pay gap figures have faced criticism for being a "horribly blunt" tool to examine an important issue, complicated by the fact that not all businesses have approached reporting in the same way, making like-for-like comparisons difficult. For example, PRH, HarperCollins and Pan Macmillan released group data, including their distribution arms, which often employ more men in lower-paid jobs, whereas Hachette also released data for Hachette UK Ltd, the legal entity where its distribution arm was stripped out, showing a far larger pay gap between men and women. PRH, HarperCollins and Macmillan all declined to reveal their gender pay gap data with their distribution arms stripped out to The Bookseller, a source of frustration to some staffers.

Taken alone, for example, the Random House Group as a separate entity has a median gender pay gap of 13.9% and a mean of 16.4%. Penguin Books and DK together had a median pay gap of 9.5% in favour of women, and a mean gap of 6.1%.

MPIL’s gender pay gap also needs to be understood in relation to the composition of the wider business—its distribution arm has 290 employees, who outnumber the 230 staff of Pan Macmillan.

Similarly in the wider trade, at wholesaler Gardners, men make up at least three-quarters of each of its four pay quartiles, and women are paid a median hourly rate 0.1% higher than men, and a mean hourly rate that is 3.20% lower than men’s remuneration. At Amazon UK, women on average occupy less than a third of jobs in its UK workforce across pay quartiles, including its warehouses. Its median gender pay gap was 0.7% in women’s favour. However, drilling down into its sub-entities, its non-warehouse divisions reveal far wider pay gaps in men’s favour: for example, at Amazon Video the median gender pay gap was 56% pro men.

Another trend that has emerged from the pay gap reporting is that men often dominate technical roles, where salaries are typically higher. The issue is likely to have influenced the numbers. For example, while 77% of PRH UK’s staff are female, its tech roles are dominated by men (73%).

Bonus pay

Generally, bonus pay across the trade is weighted in favour of men across the mean and median averages, although there are a couple of exceptions.

Companies have hastened to point out that the bonus pay gap can also be exacerbated by the number of women working in part-time roles, since the figures are not calculated pro-rata. For example, HarperCollins stressed its bonus pay gap (14% median, 47.9% mean) was magnified by the fact 20.5% of its female staff work part-time, in comparison to 2% of its male workforce. Hachette made the same point when reporting its bonus pay gap (for the Group, its median bonus pay is 1.65% lower,

and mean bonus pay 67% lower, for women) stressing that 89% of its part-time workers are women. PRH UK echoed the sentiment; although its mean bonus gap is 11.3%, it said this had been compounded by the fact that 87% of its part-timers are women.

Minding the gap

Emma House, the Publishers Association’s deputy chief executive, has warned that "behind the headline figures, this is a complex area and there aren’t quick and simple solutions." However, she said that understanding the issues the industry faced was key to being able to tackle them. "Publishers welcome the opportunity assembling this data has given them in terms of looking at where they are and the contribution it makes to their understanding of where they need to focus their efforts," she said. "It speaks to the industry’s commitment that some publishers not required to report have done so, using the opportunity to reflect on where they are and where they want to be."

Most companies who reported their gender pay data revealed schemes to tackle the issue.

They include development programmes, mentoring and unconscious bias training, along with family friendly policies, including increased maternity pay, better support for returning-to-work mothers and more flexible working.

PRH UK is also introducing pay banding in the interests of transparency, while Hachette aims to make sure women make up two-thirds of its top pay quartile by 2020. The company has also been hosting workshops of small groups to discuss the gender pay gap results—an exercise that has so far attracted the participation of more than 100 people in the company.

"They have been really open, honest and full of constructive ideas as to how we can address the gap. We have already announced some measures and others will come after all the workshops are finished at the end of April," said Hachette c.e.o. David Shelley. "We want to be a truly equal, diverse employer in every sense, and to do so we have been extremely open about our results, not excusing or whitewashing anything, in order to analyse what the results mean for our London publishing offices as well as for our distribution centres."

House added: "Inclusivity is genuinely at the top of the agenda for our members. They take it very seriously indeed and many already have excellent initiatives under way. They are committed to reaching out to a wider pool of entrants and promoting talented people once they are in—although there is a collective sense of there being more to do."