You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Stop being ‘nice’, start doing good: 15 steps to doing better

We pride ourselves on our beloved industry of creative, bespectacled, cardigan-wearing, nicest-in-the-biz book-pushers. Niceness, it is often implied, supersedes bias; a smile on the lips holding more weight than the words that come out of them. It comes as no surprise then that for many publishers—individuals and companies—“doing the work” ended where it all began, with a social media post.

But what does the fact that 2020 was often the first time Black people could disclose what they endured for decades reveal about publishing? What does it mean when, historically, white colleagues have been privately invited to get a foot in the door while our entry and continued success is predicated upon sticking in a pinky with the reasonable expectation of that same door getting slammed?

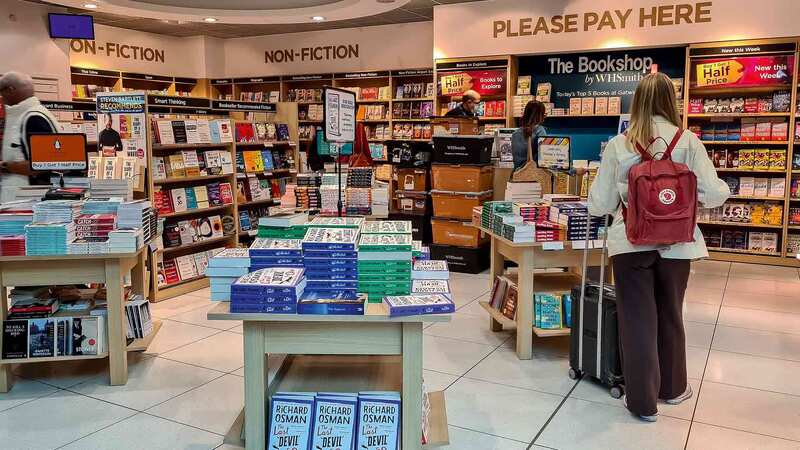

These questions are ultimately at the centre of every industry conversation around diversity, inclusion and the lack thereof. Like white colleagues, we have a personal drive and professional commitment to create and sell books to as many people as possible. We love books. We spent penniless years at universities, bookshops or offices, we have pitched myriad novels and ideas, emboldened by the sincere belief in books as education, books as escapism, books as therapy—often even above all else, including our sanity.

Our origin stories resemble one another’s: aptly gregarious, but invariably steadfast in our belief in “reading time” as a sanctum of sorts, an unbreakable chasm between flow state and stimulation. Yet somehow, in majority-white boardrooms and meetings, this inalienable fact often gets swept aside.

Having collected opinions from Black people across the publishing industry over the past year, we created a publishing manifesto: 15 steps to doing better. Here, we dig into three key points. We are often asked by white colleagues, whom we have the same day jobs as, to take on the additional labour of fixing the racial biases we endure; a Sisyphean (t)ask. We hope the below can serve as sufficient inspiration for why and how we wish to see tangible, lasting change that will prevent this exclusive Black Issue from turning into a recurring reiteration.

Describing Black authors

A major issue underlined was how we present the work of Black authors—from cover design to cover copy and similar assets. Emma Paterson, literary agent and director at Aitken Alexander, shared a poignant insight: “Too often, I see copy that elides character, story and form in favour of the ‘issues’ that the work interrogates, or the ‘take-aways’ that it teaches. For one thing, teaches whom? For another, every time I read copy like this, I think to myself: ‘But who is the novel about? What happens to the characters in this book? What do they feel? How do they change?’ It may seem a trivial complaint, but I think it speaks to a foundational challenge: how to publish Black fiction writers not as educators but as the storytellers and form-innovators that they are, and have always been.”

This goes hand-in-hand with a comment from a publishing employee who asked to remain anonymous: “More training needs to be done with editors who are not from a BAME background when they come across manuscripts they are not normally ‘accustomed’ to reading.” We considered how white editors are often praised for publishing authors of colour, but editors of colour feel vulnerable to pigeonholing for doing the same. Conversely, white editors are rarely probed over their all-white lists.

Empowering Black authors and employees

Many agreed that one of the most powerful ways to empower Black authors and employees is to allow them to express their views on a variety of topics, not just their Blackness. We heard stories of companies that announce new employees with no mention of their qualifications or publishing interests, merely evidence of their brownness. Others where junior employees are called the name of sometimes two or three other Black people in different roles, even as white counterparts with identical names are easily distinguished.

On publishing more Black authors, Natalie Jerome, literary agent at Aevitas Creative, said: “The current publishing ecosystem continues to operate through a very narrow prism, struggling, it feels, to redress old imbalances and startled by social media, which shines a light on these glaring omissions. It doesn’t need to be or feel this painful. Black authors have much to say and share for everyone to read and enjoy and in every genre. We’re not asking permission from gatekeepers who currently don’t look like us to tell our stories. We’re here to share our stories so that we understand, learn from and accept one another as people. For that is the business of books. We don’t need permission to publish!”

Paterson shared an anecdote of being pigeonholed as a Black agent. Having been invited to speak on a panel for aspiring writers, she was dismayed to learn that the subject was cultural appropriation, whereas her colleague was talking on the same day about novels’ openings. “I spent the duration being asked by white writers whether they had my permission to write from a variety of perspectives. Not a word about craft or story or character, the things I actually got into publishing to spend my time thinking about.These are distractions and distortions that permeate the publishing landscape. Of course, they are not everywhere, but they are present enough to be damaging our collective literary culture.”

My personal contribution? I can finally scoff when remembering the co-worker who spontaneously handed me a book about Africa in my first week, but not before telling me I’d never get ahead and should leave the industry. Or how once, on the completion of a final-round interview, an evidently Unicef-ad-obsessed interviewer concluded with: “And, tell me, if you don’t get this job... can you eat?” (White publishing friends’ eyes widen whenever I share such tales, as though I possess a singular, masochistic proclivity for institutional anti-Blackness.)

Understanding Black audiences

The final major area identified through discussions was around Black audiences and how to reach them. There remains a serious lack of education about Black readers, and an assumption that people of colour generally don’t read.

Nelle Andrew, literary agent at Rachel Mills Literary, said: “Consider representation versus portrayal: when you acquire a book or think of a position where you’re looking to promote diversity, think of the portrayal. Think of how this will be seen and the message you are putting out there. You want to do better—think harder. Think about what you’re saying about us as much as what you’re saying to us. This is what we need to see more of. Don’t ask why we aren’t coming to you, but what you can do to appeal to us? The problem isn’t always external... sometimes the rot has to be addressed from within.”

I would like to end with a comment from #Merky Books senior commissioning editor Lemara Lindsay-Prince: “The time for tangible change was yesterday. Statistics are a distraction. Start making steps towards redressing the imbalance and inequity within the entire operation of publishing.”

We invite those in the publishing industry to reflect on these 15 points weekly as individuals, and review this monthly as businesses.