You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

UK attendance drops at CCBF as China children's market shifts

Just 11 UK publishers exhibited at Shanghai International Children's Book Fair (known as CCBF), a drop of more than 50% year on year - 23 were in attendance in 2016 - amid ongoing concerns that Beijing is keen to stem the flow of overseas-originated titles being published in the country. However, many of those who did make the trip from the UK reported buoyant trading.

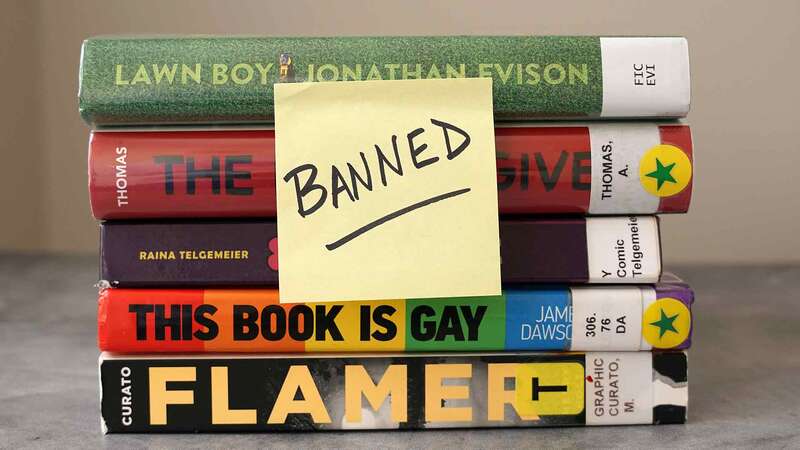

The disquiet stems from claims that copyright imports are being actively restricted by new government policy, with privately owned publishers in particular struggling to secure state-distributed ISBNs for imported titles. One UK publisher, speaking anonymously, told The Bookseller that 70% of the rights deals it had struck at last year’s fair had not come to fruition as a consequence of its Chinese business partners struggling to secure ISBNs for the books in question.

Chinese publishers and retailers, meanwhile, say they are seeing explosive growth in home-grown kids’ books. Dangdang, which has a 45% share of the country’s online book-buying market, told The Bookseller it had recorded “a huge increase” in the proportion of domestic children’s titles it was selling. China-originated titles account for around 30% of all book sales in the country, with imported titles responsible for some 70% of sales. However the former is growing at a faster rate: sales of Chinese titles in 2017 to date are up 40%-42% year on year, whereas international titles’ sales growth is around the 30% mark - still very high.

“On a policy level, there’s a huge push for children’s books about Chinese culture as part of [a programme that aims to] build China’s cultural confidence,” commented Dangdang’s children’s books general manager Liu Yu. He added that titles that celebrate Chinese festivities, such as Chinese New Year and the Mid-Autumn Festival, may be prioritised ahead of those that celebrate more Western-oriented occasions, like Christmas.

Wu Shuangying, vice-president of Hunan Juvenile & Children’s Publishing House, which has traditionally focused on domestic publishing, said the growth in output and sales of original Chinese content was a “key trend” and that the market had “recovered” and “matured” as a result of cultural shifts and dialogues that have promoted reading, supported by the state.

“Chinese bestsellers now sell 10,000 or 20,000 copies, and there are many new, well-funded literary prizes which are lucrative and attractive for authors. The government is nurturing home-grown talent, yes...but it is also to do with quality. Before, the quality of Chinese writers was not that high; now, it is improving a lot. And it’s not just about the subject [of the book], it’s about [its] presentation and the aesthetic too - that is really important,” she said.

Thinkingdom, a leading private Chinese publisher whose list is mostly comprised of foreign titles in translation, said it was “increasingly” looking to nurture home-grown talent. Vice-president Wang Yue said it had now recognised the “big commercial opportunities” represented by investing in the home market as part of a “long-term strategy”.

Xu Jiong, director of the Shanghai Press & Publication Agency, which organises CCBF, said that selective importing of foreign titles was part of fostering an environment in which original Chinese content can flourish, but dismissed reports the government was actively restricting the issue of ISBNs as “rumours” and denied it was levying any such restrictions. “From the part of the government department, we are concerned about one phenomenon: this year many publishing houses have [introduced a lot of] foreign children’s books and copyrights,” he said. “And sometimes we are having too many of them, because it is easier to just import foreign books than [it is] to identify domestic talent... So we are levying a flexible means to remind the publishing houses to reduce the introduction of mediocre and low-quality [foreign] books.”

Publishers Association chief executive Stephen Lotinga commented: “China is an incredibly important market for the publishing industry, so it is of great concern that children’s publishers are encountering an increasing number of barriers when exporting there. We have noticed a distinct decline in the number of children’s publishers travelling to the Shanghai International Book Fair this year and that’s directly related to China’s policy and the impact it is having on the market. This is an issue that the PA continues to raise with both the Chinese and UK governments.”

Publishers at CCBF, which is in its fifth year, reported successful trading, however. Michelle O’Doherty of North Parade Publishing said sales had been healthy and the fair was busy. “Because we mainly work with state publishers, we’ve not had any problems, although I know other publishers who have had issues,” she said. “We’re also more factual, and it’s fiction portraying Western ideals, not Chinese ideals, that is the kind of thing I think they may be having trouble with.”

Nick Ackland, m.d. of I am a Bookworm, who was visiting CCBF for the first time, said: “Whatever my expectations were, they’ve been exceeded. Our age range is 0-5 and the country is relaxing its one-child policy; I think there is huge demand.” David McMillan, group export senior sales manager at Walker Books, said: “There’s been a massive increase in the past three or four years in export sales. China is a really important market and it’s well worth us coming.”

According to a report from book data company OpenBook, sales of kids’ books accounted for 23.5% of China’s total retail book market in 2016. The overall market generated CN¥70.1bn (£7.97bn) last year.