You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Dwindling UK libraries have 'fallen into trap', warns campaigner

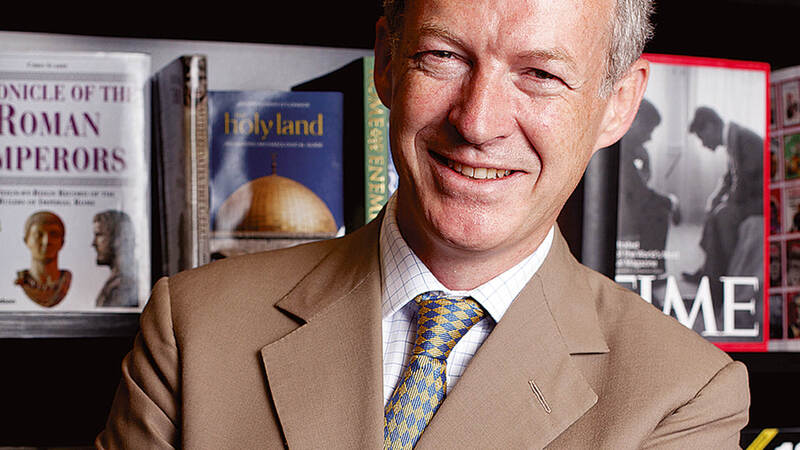

New figures showing the dwindling popularity of UK libraries suggest the facilities have fallen into a “trap” and a new approach is needed, campaigner Tim Coates has said.

Coates, a former Waterstones m.d, commissioned consumer research on where readers get their books. Three hundred UK residents were polled about their reading habits for the survey, with the figures showing 87% had “made use of a book” in the previous 12 months.

Despite the high reading figure, the number of adults who had obtained their last book from a library stood at just 8% for those aged 18 to 35, 10% for 25 to 54-year-olds and 12% for those aged over 54. Among younger readers aged up to eight, only 8% used a library with just 17% of older children from the small sample making use of one.

A larger survey commissioned by Coates of 1,100 people in the US showed 81% had used a book in the previous year, yet the use of libraries was far higher. Twenty-one percent of children aged up to eight had accessed their last book from a library, soaring to 32% for those aged between eight and 17.

Coates, who differs from most experts in saying the UK decline is not down to investment, said the poor UK figures came from libraries becoming more like community centres—something he claimed had not happened in the US.

Coates explained: “It’s because a long time ago the UK public library sector took a path which said we’re not just about books anymore. The US have never gone down that path and still talk about the value of libraries in the community. They’ve never left the standpoint that the essence of them is about books and reading. They say we mustn’t fall into the trap the UK has fallen into.

“It’s an important message not just to libraries but to publishers too. In the US libraries still play an important part. In the UK they just don’t at all.”

Coates, who has previously called on publishers to tackle the library crisis, claimed: “It’s this constant message from the library sector that we’re not really about books. It’s gone on so long that headmasters, local councillors and people who fund them have just said ‘ok, children don’t read, they watch TV and go online’.

“It’s not that they’ve been deprived of investment, it’s that they talked themselves out of it. People have stopped investing because nobody uses them but what came first was the denial of the importance of books.”

However, Libraries Connected, a membership body representing public libraries in the England, Wales and Northern Ireland, pointed out there were crucial differences between the UK and US.

C.e.o Isobel Hunter said: “We have a different funding system to the US. Much of their funding is decided locally by votes and their private philanthropy is far more developed so it’s difficult to make direct comparisons.

“In the US, there is legislation which requires publishers to make their e-books available to libraries which is not the case in the UK. Hachette, one of the big five publishers, does not allow any titles to be bought by libraries while Hachette US does. The net result is that UK public libraries have simply lost customers who prefer to read in a digital format because we are unable to offer a comprehensive e-book service.”

Cuts to council funding and the reduction in the number of qualified public librarians had also led to “fewer people who understand how to develop and promote collections to their fullest potential”.

She told The Bookseller the organisation believed reading was at still at the forefront of library activity but there was success to be had by engaging communities around it through initiatives including baby rhyme time and The Reading Agency's Summer Reading Challenge.

“We know that all libraries have a much wider remit as a resource for community information,” she said. “However, we also believe that libraries should be in the business of providing a variety of learning and inspirational experiences to their local communities.”

Figures released in December showed spending on books in public libraries had plunged by 20% in the 12 months to the end of March 2018. In England alone, 105 libraries closed, while 14 more were passed to volunteers to control. Councils in areas including Essex, Derbyshire and Ealing are all considering cuts to their library services this year.

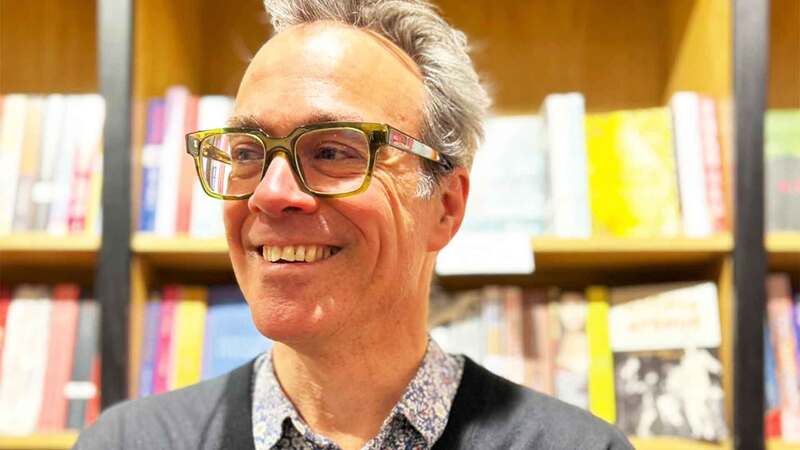

Nick Poole, c.e.o. of library and information association CILIP, said research on take-up was useful and the rise of blogs and book groups showed the British love of reading was undiminished. But he insisted the main factor for the falling use of libraries in the UK is facilities being run “on a shoestring” due to an investment squeeze.

Poole said: “There are essentially five ingredients which make up a successful library—we need bright, attractive spaces, professional staff, good-quality book-stock, good IT and a diverse programme of activities to help keep users interested. There is no doubt that better books in libraries equates to more use. The problem is that after 10 years of public sector austerity and local government cuts, we are running the service on a shoestring—which means we can’t deliver the great libraries and high-quality stock that people want everywhere across the UK.

“That is why CILIP is working with the Arts Council England, Department for Culture Media and Sport and Libraries Connected to issue a call for sustainable, long-term investment in libraries in the next Spending Review. Britain loves books and reading, and libraries have the potential to do so much more to meet this demand—but only if they get the investment they desperately need.”