You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

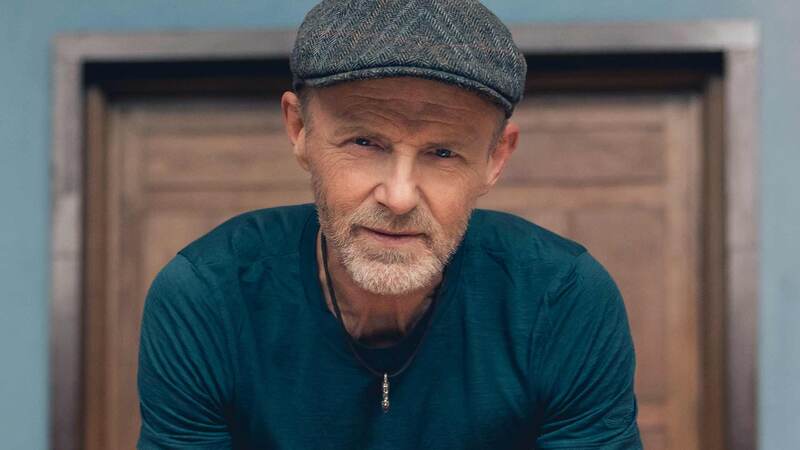

'Booker Prize is for readers first and publishers last', says Wood

Gaby Wood, literary director of the Booker Prize Foundation, has said prizes like the Booker are for readers first and foremost, and also that they should be treated as an investigation, rather than an act of judgement shaping the canon.

Wood addressed the role of prizes in a panel on "How can we get books back to the top of the cultural agenda?" during Futurebook Live on Monday (25th November). She appeared in the session, chaired by journalist and author Anita Sethi, alongside Stephen Page, c.e.o. of Faber & Faber, Carole Tonkinson, publisher at Pan Macmillan imprint Bluebird and Dialogue Books publisher Sharmaine Lovegrove.

“That wasn’t my doing,” Wood said first, addressing the judges’ controversial call to flout the rules of the Booker Prize this year in selecting two winners, Bernadine Evaristo’s Girl, Woman, Other (Hamish Hamilton) and Margaret Atwood’s The Testaments (Vintage). She went on to say that, were it her decision, she "wouldn't have been for it".

"The results we’ve seen from it [the double win] are totally to do with the personalities of the two winners and how incredibly gracious and generous they have been. So that was a win for them and I think for the prize. I wouldn’t have been for it. I think it’s really upsetting for the losers; it’s much worse to not win when two people have," said Wood.

Of the role of the prize, she continued: “I think on the whole, my predecessor possibly thought of it [the prize] as being more connected to publishers because he was a former publisher. I think it is for readers first, writers second, and publishers third – and they are all completely interrelated. The impact on the writers is enormous, not just the money but the effect afterwards.

"Our job really is to find readers – and by that I mean people on the panel [of judges] – who will welcome as much as possible: are those readers receptive to what is going on that’s most exciting in writing? Do we need to change the rules if that’s not the case? Is the most interesting writing going on in a kind of hybrid form and does this mean the judges aren’t going to see those books? In which case they’re missing a trick. In the international prize, short stories are eligible because for some countries and in some languages that’s the predominant form so there has to be room for that.

"So [our job is] just to be a little bit flexible and capable of adjusting to the receiving end of things, and also not to think of it as an act of snobbery, in fact not really to think of [the prize] as an act of judgement at all – to think of it as an invitation to investigation or an act of welcome [to writers] of some kind.

“Are we biased? Are we best placed to say what is good in this? That [imbues] the judges with an enormous responsibility but it is a bit different to saying I’ve arrived at a certain point on my CV and I’d now like to be a Booker judge. I feel the impact can be great if the panel is responsible and takes that ethical responsibility quite seriously.”

Questioning whether the conversation in the judging room should be the focus over and above the prize winner, she said: “The rules of the Booker Prize state the actual conversations of the judging is confidential but for me, watching them, that’s the most interesting bit. Historically, the judges didn’t meet all that regularly but now they meet once a month, and sometimes it is quite moving …

“Could the Booker Prize be responsible for facilitating those sorts of discussion [a book group concept] given that they take place at the core of the decision-making and are much more interesting, frankly, than the decision-making itself… I don’t really know how to do that but I think it’s of interest.”

Lovegrove said as part of the session she thought “publishing is obsessed with publishing and not the art of reading”, and that there were lessons to be learned from industries like TV and film. “I do find it really shocking that people have been living in this white middle-class bubble and then are wondering why they haven’t been relevant to culture,” she said.

Carole Tonkinson, publisher at Bluebird, rallied against snobbery within the trade in terms of the successes it chooses to celebrate. She said further it was her wish bookshops become “a more democratic space”, open to “people who don’t think of themselves as readers or part of the cultural elite”.

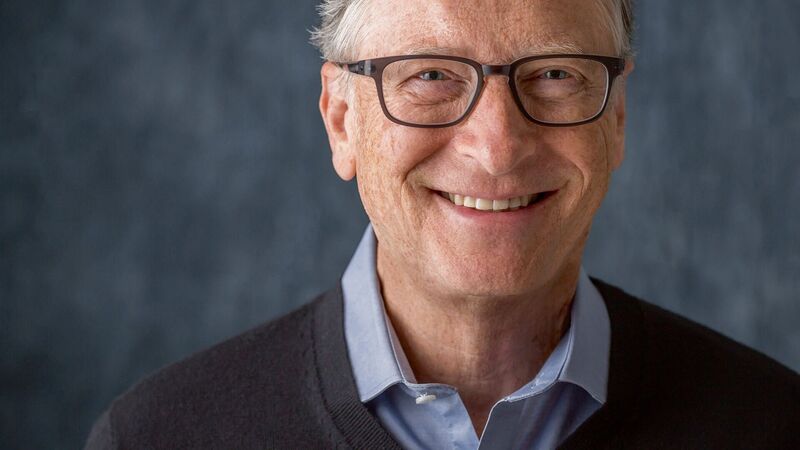

Stephen Page, c.e.o. Faber, said, although popular books should not be overlooked, readers are “not well served if businesses are too wrapped around the market” and cautioned "not to let the market shape us too much”. Looking forwards, he said: “There is no room for any complacency. We have to move at some pace and at the same time not to lose the thing that is special to our world, which is a lot to do of our belief in and support of the marginal, the things that appear strange. You can get a book off the ground for relatively little money, you can’t get a film off the ground. To get to know our readers is critical; at the same time we should not let the market shape us too much. We should be shaped by our own interests and our own compulsive tastes – but in order for that to be true for a wider industry, we have got to transform the industry. It’s got to happen, it’s got to continue. There’s no room to say somehow we’ve done something. We’ve not done anything yet: we have begun.”