You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

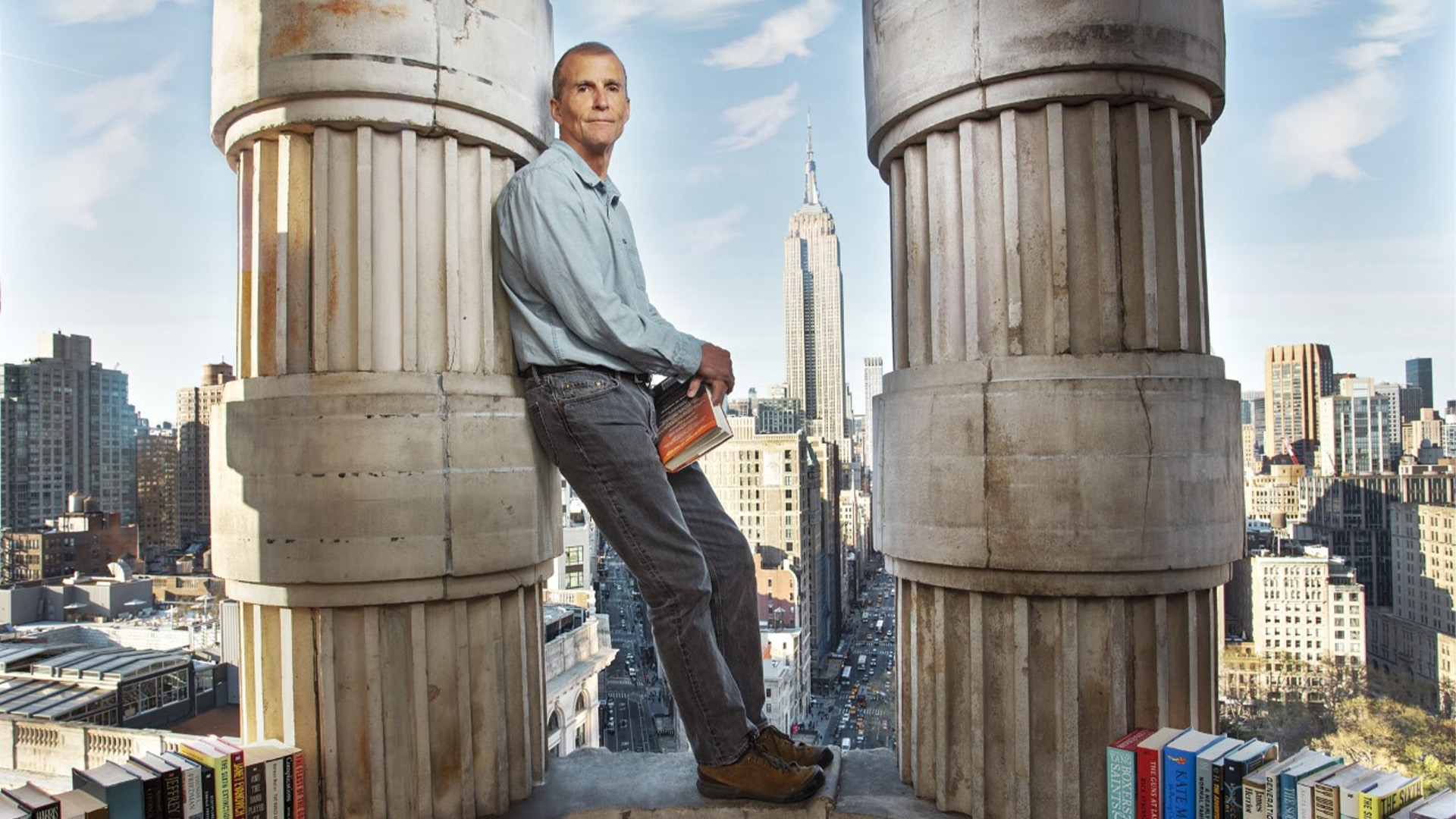

Turning Pages (and Reading Between Lines): John Sargent Writes a Book

John Sargent, who ran Macmillan globally until 2021, is known for cowboy boots, verbal straight-shooting, formative years in Wyoming, and four decades in the book business, more than half at Macmillan.

In 2012, he was the last publisher standing who tried to speak antitrust truth to the Obama administration Department of Justice during the Amazon/Apple/agency e-book trials and tribulations. He didn’t succeed. It cost Macmillan $30m, but Sargent’s reputation as a leader (and maverick) only grew. Having had a hand, one way or another, in thousands upon thousands of books during those 40 years, this autumn he’s involved in yet another, but with a difference. Turning Pages: The Adventures and Misadventures of a Publisher, coming from Arcade in the US in September, and Simon & Schuster in the UK in November, bears Sargent’s byline and follows the chronology of his life. Just don’t call it a memoir (even though admiring blurbs already have).

“I hate the word memoir,” he declared to The Bookseller during a relaxed face-to-face in the summery Hamptons a hundred miles from New York City. He recalled that when he began work on the project – it took a year and a half to write – he wanted to emphasise what the Big Five company he’d led for so long was about, “not focus on what John Sargent is about”. It was, in a way, an effort at “how to say goodbye”.

Sargent had been one of three executive board members of Macmillan’s corporate overseer – the family-controlled, Stuttgart-based Holtzbrinck Publishing Group – and it seemed he’d remain in the saddle forever. Then Covid-19 came. He and his boss and fellow board member, c.e.o. Stefan von Holtzbrinck, had worked very well together – they’d become personal friends. But as Sargent put it, “Stefan worried that, with the pandemic, we wouldn’t have enough financial resources to make it through.” Von Holtzbrinck devised a plan, and in August 2020 when Sargent refused to carry it out, knowing that if he did, “hundreds would lose their jobs and all others would suffer an increase in their already overflowing anxiety,” he was axed. His services wouldn’t be required in 2021 or thereafter. Ironically, without him there to execute it, von Holtzbrinck’s plan was never implemented, “and never will be,” Sargent insists.

His life having taken that turn, he found himself thinking about a book, one that he’d read several times. Sargent’s long-dead great-grandfather had written and privately published it after becoming sick; the old man had wanted, before he died, to use life stories to explain to his family, friends and employees what he’d done all those years at work. Frank N Doubleday, known as “Effendi” – a play on his initials – had, like his great-grandson, done a lot, having co-founded and run the publishing company that bore his surname, which by his death in 1934 was America’s largest. It was time, Sargent thought, to do “the same thing for my kids.”

One thing Sargent did not want to do: be introspective about childhood, family, the things that made him tick, those same kinds of things that propel most – that word again – memoirs

A Stanford graduate (shunning labels, he does not automatically offer up that bit of biography), Sargent had always enjoyed writing – when younger, he’d penned and published with other houses three children’s books under the pseudonym (and anagram) S T Garne – and now determined to put on paper a series of anecdotes that, if carefully read, would allow a person to understand quite a lot about the business he loved. He wanted to “walk the thin line to make it interesting to people who are in publishing, but also to the lay reader interested in books”.

Describing himself as “happy in my life, a forward-looking guy,” and married to Connie, mother of his two children and no slouch herself (as Sargent recounts in his book, the couple met in 1982 when each was pursuing an MBA at Columbia’s Business School), he wanted to pass along only “the good stories”, moments from his life in no particular order that would entertain or inform. Some involved former colleagues like Sally Richardson, Tom McCormack and Matthew Shear, but more featured encounters of the famous-people kind, some of whom were authors.

The boldface names ranged from Monica Lewinsky to Hillary Clinton, Michael Jackson to Jimmy Carter, Britney Spears to Lord Jeffrey Archer. Each story was telling in its fashion, and was told in an amusing, wry, spare and rather modest voice. Sargent’s favourite among the famous-people kind dated from his early days at Simon & Schuster, and featured Sarah Ferguson, a.k.a. the Duchess of York, her children’s book, Budgie the Little Helicopter, and S&S’s then-supremo, Dick Snyder.

He also wanted to put the record straight about important controversies in which he’d played a part: episodes like the fight over e-books; publishing Edward Snowden; standing up to Donald Trump to defend Michael Wolff’s Fire and Fury. Determined to be scrupulous about facts, he asked friends who’d been present to read sections, and enlisted the aid of Publishers Lunch impresario Michael Cader to make sure his detailed account of the e-book drama was as correct as humanly possible.

However, one thing Sargent did not want to do: be introspective about childhood, family, the things that made him tick, those same kinds of things that propel most – that word again – memoirs. “If you spend a lot of time internally gyrating, you don’t get a lot done,” said the man who was far more comfortable talking about doing – even those times when he metaphorically ended up with pie on his face – than about feeling.

To publishing people of a certain age, it was common knowledge that Sargent’s own father, John Turner Sargent Sr had run Doubleday for 15 years – after all, they shared the same name

When his friend and former employee, Farrar, Straus chairman and executive editor Jonathan Galassi, agreed to read a draft, Sargent assured him: “Nobody wants to hear about little Johnny going west to Wyoming”. It was only after Galassi and others, like Gail Hochman, who signed on as Sargent’s agent, read the draft and countered that everybody wanted to hear about little Johnny, and the book needed to follow the chronology of his life and contain more personal “connective tissue”, that he, to a certain extent, obliged. And so, although still full of those entertaining, informative publishing adventures and misadventures that roll along at a page-turning clip, the reader now glimpses a husband, father, and in a few brief, charged, very moving passages, a boy whose childhood was far from usual.

While hardly spilling all, he’s made it possible for readers to read between the lines and sense how, and who, 66-year-old John Turner Sargent Jr came to be. Sargent’s favourite story in the more intimate vein is a classic tale. It’s about surfing with his son Jack, and much more. It closes out the book.

To publishing people of a certain age, it was common knowledge that Sargent’s own father, John Turner Sargent Sr had run Doubleday for 15 years – after all, they shared the same name. Sargent Sr’s glory days were in the 1970s, when within a two-year span, the company published Jaws by Peter Benchley and Roots by Alex Haley. But what many didn’t realise was that Sargent’s mother Neltje was Effendi’s granddaughter, a Doubleday. She was only 18 when she married the handsome, charming, 28-year-old up-and-comer who was working for her father. Two children, a girl, then a boy, arrived quickly, but the marriage didn’t last. Sargent’s parents separated when he was six, and divorced two years later. At that point, his mother moved with him and his sister Ellen from Park Avenue to a Wyoming cattle ranch where life became very different.

Three hours of chores on the ranch were to be done each school day. Sargent’s mother presented to her children a stream of “unexpected moments, small and large”, where she did what she did, and they had to adapt, come what may. A woman of “tremendous courage”, she was also, clearly, of an iron and unpredictable will. Most summers, he and Ellen would toggle back to the East Coast to nannies, a beach house, their father, and “his endless string of girlfriends”.

Of time actually spent with his father, Sargent wrote, “the silence between us took its usual place. I spent my whole life trying to make sure I was judged for who I was and not who they were”, he confessed to The Bookseller.

"The silence between us took its usual place. I spent my whole life trying to make sure I was judged for who I was and not who they were"

Growing up in Wyoming, talking about his parents – “that wasn’t something you’d talk about. It would have made you different”. At first it was difficult to write about these two “complex” people, but he found a way that worked for him. A man of tremendous energy – the kind that has often characterised the best publishers – in story after story, Sargent also exhibited physical bravery, in mountain-climbing, wilderness survival, skiing, surfing. He’s a guy who takes risks, physical, business or, in publishing, a book like this.

“I always try to prove and test myself: don’t most people do that?” he wondered aloud. “If you don’t push yourself, you don’t get better. I enjoy the exhilaration of getting past fear – there’s a joy in that.”

Two houses were interested in acquiring the book. Sargent is happy to be published by Arcade, now part of Skyhorse. When it was independent, he’d once looked at it as a possible acquisition. Editor Mark Gompertz read the manuscript and liked it, and in a previous life had worked many years for the late Carolyn Reidy at S&S. Sargent “very much admired” Reidy, another publisher willing to speak her mind, and knew she admired Gompertz. It’s “a fantastic feeling,” he said, still pinching himself, “when someone says, ‘I want to publish your book’."