You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

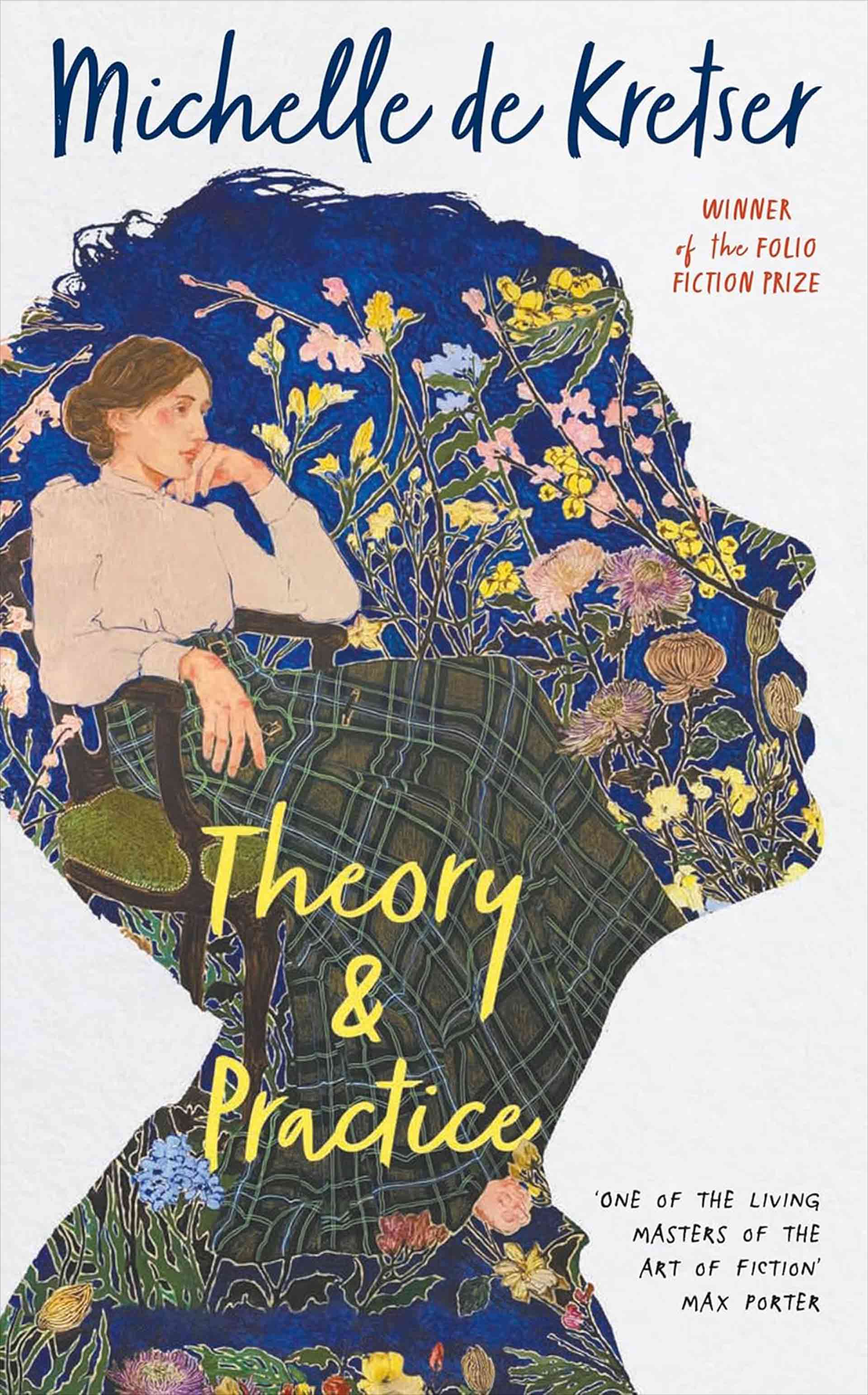

Folio Prize winner Michelle de Kretser on her Virginia Woolf-influenced new novel

Alice O'Keeffe

Alice O'KeeffeIn a nutshell, I read books for a living. I interview authors for The Bookseller's weekly Author Profile slot and write the monthly New

...moreFolio Prize for Fiction-winning Michelle de Kretser on blending fiction, essay and memoir in her latest novel

"A novel that doesn’t read like a novel” was Michelle de Kretser’s ambition for her eighth work of fiction, the excellent, genre-redefining Theory & Practice, her first to be published by Sort Of Books.

Theory & Practice is narrated by an unnamed writer, looking back at a pivotal point in her life. It is set (mostly) in St Kilda, Melbourne, 1986, when she was 24 years old, freshly arrived from Sydney to begin her postgraduate studies on the novels of Virginia Woolf. It’s a febrile time to be at university, full of radical ideas inspired by French poststructuralist theory. St Kilda is filled with artists and activists and the promise of lifelong friendships. The narrator considers herself a feminist (“In theory there was no reason not to be a Marxist feminist, but it was tricky in practice because Marxism in student politics was dominated by men,” she observes) but when she meets Kit, who claims to be in a “deconstructed” relationship, and they become lovers, she is made aware, and not for the first time, of the difficulty of applying theory to practice. Her love life is messy and then her academic work is thrown into disarray too when she makes a shocking discovery about Woolf while reading the English author’s diaries.

Theory & Practice was not a novel with a single starting point, de Kretser tells me over video call from her book-lined home in Sydney, but Woolf was key. In her diaries, Woolf “sets up this wish to write a novel that has a chapter of fiction, followed by a chapter of essay”. Woolf did start work on this, writing more than 100,000 words, de Kretser tells me, before abandoning it and writing The Years as straight fiction.

De Kretser decided she would have a go, and Theory & Practice blends fiction, essay and memoir in such a way that it can be hard to see where one ends and the other begins. What the novel is not though, says de Kretser, is autofiction.

Woolf indeed committed some very unpalatable opinions to paper in her diaries: “I wanted to try and tease that out a bit, about how one might acknowledge these flaws without feeling the need to dismiss this person completely from our reading or from the people we admire. It seemed to me that acknowledging was the way to go about it, rather than sweeping it under the carpet.

To acknowledge there were problems and then we can go on reading and loving the work.” The narrator refers to Woolf as the “Woolfmother” and de Kretser says: “It’s a book about mothers and daughters too. Our biological mothers and then the mothers we find, literary mothers. For my generation, Virginia Woolf was a really important figure.”

Growing up, de Kretser, who was born in Sri Lanka and moved to Australia with her family as a teenager, had no particular aspirations to write despite being a “big” reader. She read French at the University of Melbourne. “I thought I might end up as a literary scholar. And I worked in publishing, so I was always on the other side of the desk,” she says. She joined travel publisher Lonely Planet as an editor, eventually setting up its Paris office, and had been working there for about 10 years when the company introduced the option of a year’s sabbatical. Most people who took it up went travelling but de Kretser, who had been clocking 10-hour days, decided on a year of “living differently” and made plans to cook, to garden and perhaps do some book reviewing. But she was soon bored. While waiting for literary editors to respond, she decided she should probably “do some writing, just to get that writing muscle going”.

This became her first novel, The Rose Grower (1999), which she received an offer for exactly one week before she was due to return to her job at Lonely Planet. “I think if I had said at the beginning of that year, ‘I’m going to sit down and write a novel’, I wouldn’t have been able to do it. It would have been too daunting. But the mind works in mysterious ways to trick you.”

A string of novels followed, most recently the Folio Fiction Prize-winning Scary Monsters, but she has retained her editor’s precision: “I think it’s really important for a writer to be able to be quite ruthless about their own work. I would do probably four drafts before it goes to a publisher. There is no point in wasting their precious editorial intelligence on stuff that I could have fixed if I’d only taken the time and the trouble. I want them to see things I can’t see.”

"If I had said at the beginning of that year, ‘I’m going to sit down and write a novel’, I wouldn’t have been able to do it. It would have been too daunting. But the mind works in mysterious ways to trick you.”

Another influence on Theory & Practice was Ursula K Le Guin’s “carrier bag theory of fiction”, which is new to me and rather wonderful. De Kretser explains: “She was originally thinking about the way we are taught to read and to write and to value fiction, which is based on this idea of the hero’s journey.” Le Guin connected this with the hunt in traditional hunter-gatherer societies; a hunter who kills the prey, brings it back and tells the story. “But she, as a feminist, wasn’t very happy about this. She thought this was a very masculinist way to understand literature.”

Le Guin made the point that in those societies, successful hunting was quite rare and mostly people survived from gathering: fruits, seeds, birds’ eggs and so on. “All of these disparate things would be put into a carrier bag… I sort of loved that because I had all these disparate things I wanted to say so I thought: ‘Okay, I am going to make a carrier-bag novel.’

Henry James famously said the novel is a baggy monster, and I thought, perhaps my novel could be a carrier-baggy monster,” she says, laughing.

At a tight 192pp, Theory & Practice is not baggy in the slightest as de Kretser captures a time when, for her protagonist, adult life is just beginning, open and chaotic, filled with possibility. It’s witty and erudite on life and art and more than achieves the author’s aim of “a novel that reads like memoir, like truth”. Although, of course, it is “realist fiction, it’s not reality”, says de Kretser. “However perfectly realist, art and reality are two different things.”