You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

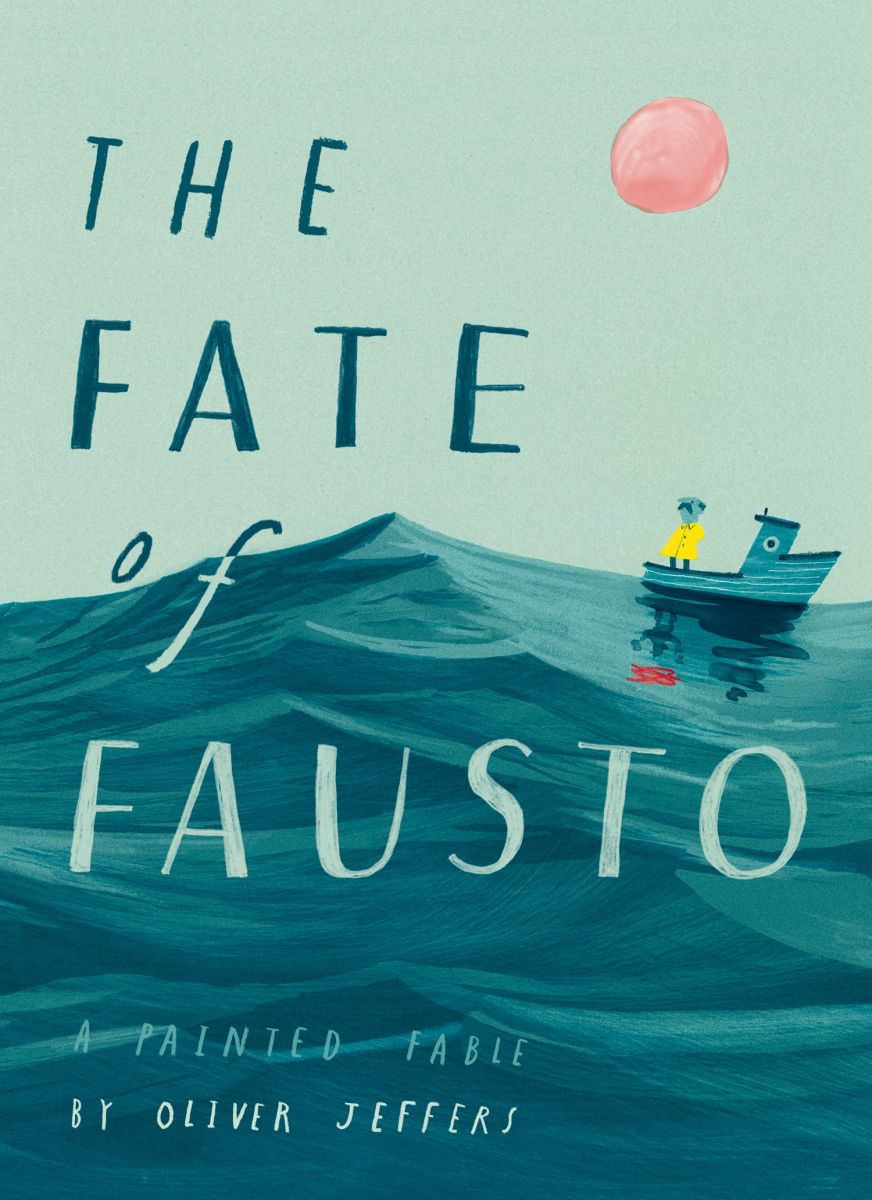

Jeffers returns with lithographic fable telling of one man’s greed

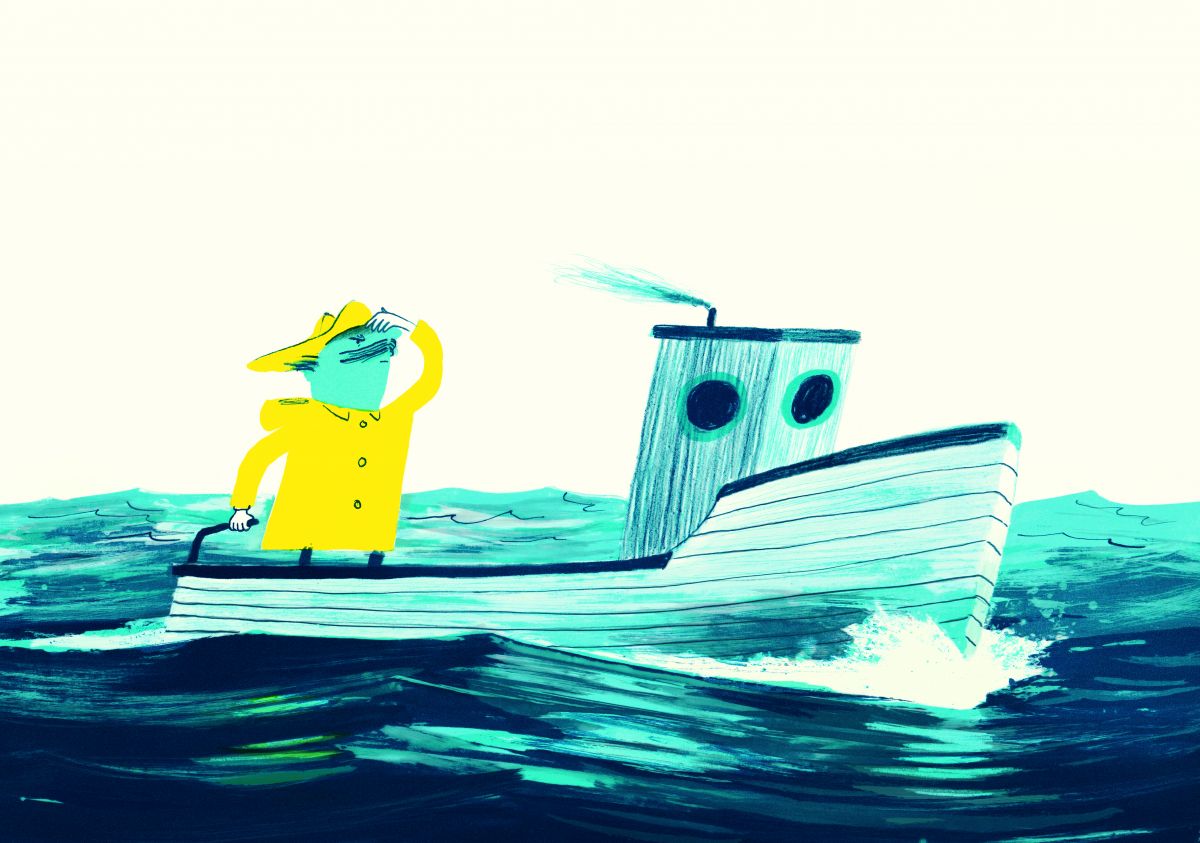

Oliver Jeffers ended up learning a "whole other language" to create Fausto, his upcoming fable about a man who wants to own everything he sees, which he made using traditional lithographic printmaking techniques at Idem, a fine-art printing studio in Paris.

Lithography involves putting ink onto a surface, often a metal plate or traditionally stone, adding colours one by one, then transferring the image onto paper. The plates are hand-made each time, resulting in unique pages, but the process was far more time-intensive than Jeffers imagined. "I thought two days would be enough [to make all the book’s images], but after three or four days we had only made one image," he said. "Two weeks ended up being three weeks, then four, five, six, eventually seven, and we ended up working from 7 a.m. until 11.p.m., including weekends."

Lithography involves putting ink onto a surface, often a metal plate or traditionally stone, adding colours one by one, then transferring the image onto paper. The plates are hand-made each time, resulting in unique pages, but the process was far more time-intensive than Jeffers imagined. "I thought two days would be enough [to make all the book’s images], but after three or four days we had only made one image," he said. "Two weeks ended up being three weeks, then four, five, six, eventually seven, and we ended up working from 7 a.m. until 11.p.m., including weekends."

Jeffers said the process was challenging for a number of reasons, likening it to painting with a three-hour time delay. "There was a gap between applying the ink and seeing the end result, but in the meantime I had to keep on painting," he said. In addition, each colour took "days and days" to get right, forcing the artist to be economical in what he used. "Sometimes creativity is inspired by boundaries and having a limited palette made the book more beautiful. So there are only two spreads with six colours [the others have fewer] and those are the spreads in the middle."

Jeffers asked London-based designer David Pearson to digitise a typeface from the 1940s and typeset the text in it, and worked with a paper marbler to create the endpapers. "The whole thing is an homage to the old ways of making books," he said. The challenge for HarperCollins was turning the prints into a book that can be mass produced, and the "last pieces" are still being figured out. "It has been complicated, but everyone has relished the challenges."

The selfish gene

In contrast to the design, writing the text was simple—it "wrote itself", he said. Jeffers, who lives in New York, was visiting family in Belfast and took a drive to the north coast of Antrim, where, inspired by a storm, he started to jot down a story about a man who thinks he owns all he sees: the flowers, the sheep, the trees, the fields. Jeffers wanted to explore the idea that while greed as a trait has in some respects served humanity well throughout history, it has no off switch. People are unhappy with their lot, he explained, and instead of thinking about what is right for society and the world, they often perceive things in terms of individual interest.

Climate change, the subject of a lot of his art, was also in his mind. "I made a social media post a couple of weeks ago when all those schoolkids were protesting, and I said something that seemed to resonate with people, which was that the planet will be fine— it’s humanity and other forms of life that are in danger."

Idem is hosting an exhibition of artwork from Fausto (it agreed to host Jeffers in return for being able to sell prints), and HarperCollins plans to run three or four events with the artist around publication on 17th September. Jeffers has more adults visiting his events than when he started 20 years ago, and does not distinguish between his work in children’s books and his fine art. "As a whole they’ve been growing together—the only difference is that children’s books have to have a beginning, a middle and an end."