You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

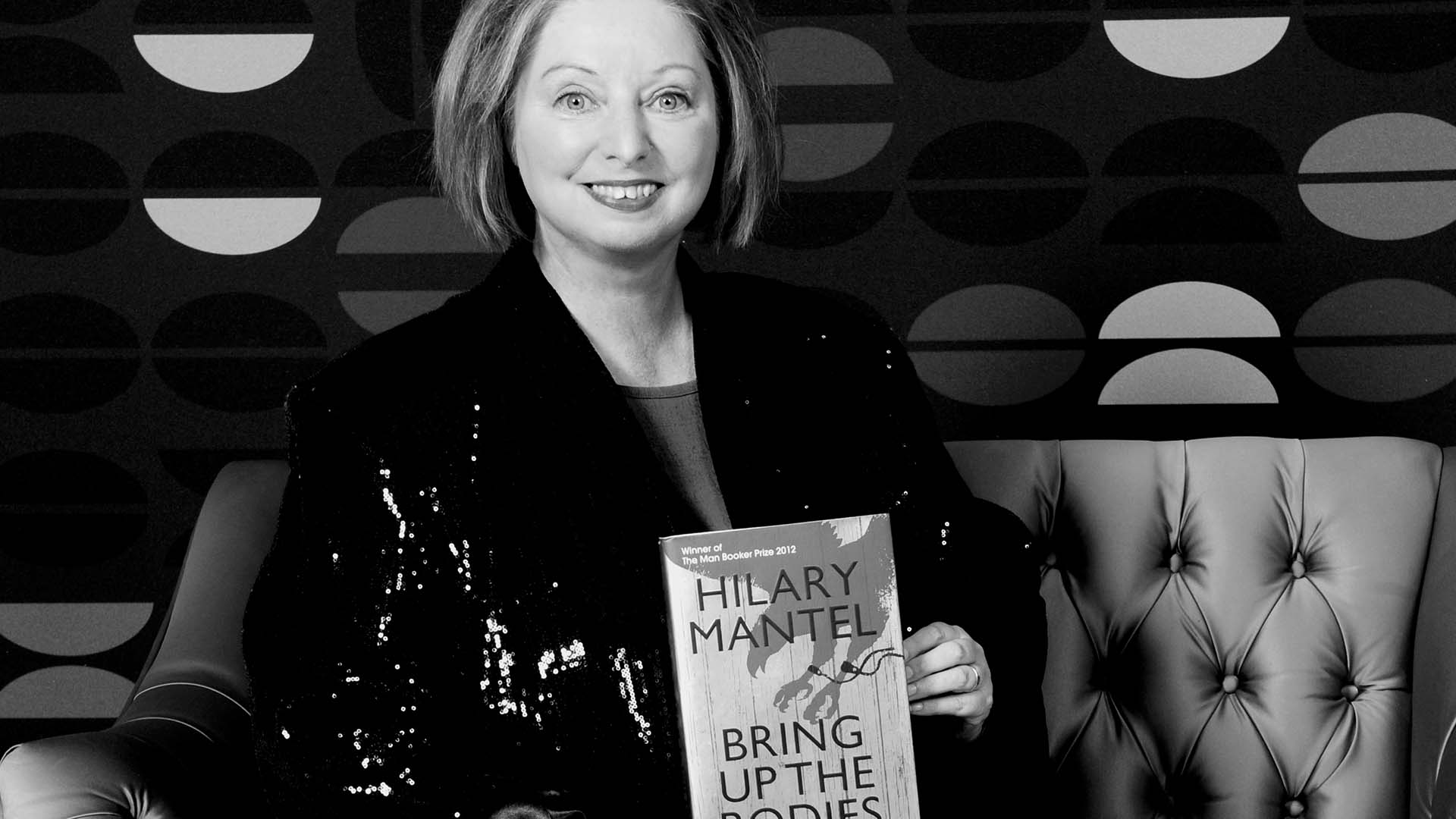

Obituary: Hilary Mantel

Hilary Mantel 6th July 1952–22nd September 2022

A manuscript came in the post from Saudi Arabia one day in 1984, a wickedly dark comedy set in the world of social work and black magic called Every Day is Mother’s Day. It was pretty well perfect, reminiscent of Beryl Bainbridge or Muriel Spark perhaps, but with a voice all of its own, creating a gothic world suspended between a weary and literal world of the Midlands in the 1970s and an alternative one leaching out into myth and horror. I met the author soon after, a modest, bright-eyed Hilary Mantel, whose background was hard to fathom but whose intensity showed purpose. After a couple of rejections I was delighted to find an enthusiastic publisher in Carmen Callil at Chatto. The freshness of the imagination and the sharpness of the humour caught the attention of reviewers and Auberon Waugh, in a stroke of genius, appointed Hilary his film critic at the Spectator. Coming to film with mock ignorance allowed her the luxury of riffing on—for instance—the uses of mud in overblown historical epics. Her satirical talent was being honed, and it led to a lifelong passion for serious films.

Other novels followed, each pursuing a different theme and period, but circling around loss, evil, magic, memory, Catholicism, childlessness; set in Saudi Arabia, Botswana, 18th century London, Derbyshire. Hilary labelled them: A Change of Climate was her bourgeois novel, Eight Months on Ghazzah Street her Saudi novel, The Giant O’Brien her Irish novel... As she moved from subject to subject, readers and critics found it hard to keep track, or yet to see common threads, but there was a sprinkling of prizes recognising the literary excellence she displayed.

From time to time there would be surprises. She rang rather sheepishly one day to say that there would be an article in the Observer including a description (and, cheekily, a valuation) of the huge historical novel she had lost hope of getting published before she had sent us Every Day is Mother’s Day: would I mind reading all 1,600 pages of it? Over a summer holiday A Place of Greater Safety revealed itself as a unique masterpiece, technically brilliant, impeccably researched, emotionally overwhelming. It took a while for readers and critics to realise quite what it was, but it did win the Sunday Express Book of the Year award and, in the years afterwards, every now and then an article would appear celebrating it as the greatest historical novel of recent times.

Speaking out

Lurking in the background was always chronic ill health. She was diffident about drawing attention to it, but decided one day to go public and write about endometriosis, which had assailed her in its most extreme form in her early 20s and had led to permanent damage. She became a prominent spokesperson for the recognition and early diagnosis of the condition. Also lurking in the background was the bizarre family history: during her childhood, her father was turfed out of the family and never mentioned again. Her stepfather Jack was an oppressive figure in what was an oppressive childhood with a severe Catholic education in a sectarian northern town. Writing about all this in her memoir Giving up the Ghost and indirectly in her short story collection Learning to Talk gave her audience some clues about the themes she came back to time after time in her fiction. On many levels this background provided the essential material for her novels, exploring life lived in different and parallel realities: the constant danger of certainty leaching into uncertainty, or disintegrating catastrophically. It is no coincidence that a seminal book for her was Sanity, Madness and the Family by Aaron Esterson and Ronald David Laing.

On many levels [Mantel’s] background provided the essential material for her novels, exploring life lived in parallel and different realities

I only once heard Hilary express despair at the arbitrariness of the publishing game. On publication of Beyond Black, indisputably her darkest and funniest novel, which had good reviews but wasn’t taking off commercially, she said to me: “What more do I have to do to make a success of it?” She’d written to the very best of her ability, promoted to the limit of her physical capacity, but saw that so much of it was a crap shoot. Not long after, when we were talking about other things, she asked tentatively if I thought that a novel giving the Henry VIII story from the perspective of Cromwell was a good idea. It wasn’t hard to say yes.

All the elements that made her unique came together spectacularly in The Wolf Hall Trilogy. Her wit, stylistic daring, creative ambition and phenomenal historical insight mark her out as one of the greatest novelists of our time, recognised of course by her unprecedented winning of two Booker Prizes for successive titles and her international success, which she embraced gleefully. While writing the books she developed deep friendships with eminent manuscript curator Mary Robertson, to whom the three books are all dedicated, and Diarmaid MacCullough, the eminent historian. She loved working with actors on the adaptations and developed a close partnership with Ben Miles, the stage Cromwell, with whom the adventure of delving into Cromwell’s life eventually became a joint activity, together with Miles’ photographer brother George. The stage versions brought her into the Royal Shakespeare Company, which she became a patron of: a huge delight as theatre was one of her lifelong passions.

A critic’s eye

Alongside the writing of the novels was a continuous output of reviews and features, several years under contract with the Guardian, regularly writing for the New York Review of Books and the London Review of Books, covering an enormous range, from fiction to history, psychology, showbiz and, infamously, royalty. Royalty was a lightning rod for her: a world of appearances and power and projection and vulnerability which lay at the heart of her historical writing, but also in the media spotlight today. A long piece for the London Review of Books, in which she pleaded for the media and the public to leave royals to their private lives, was wilfully and radically misquoted by the tabloids. She sat out the media storm cheerfully. Another even more heated controversy arose when she wrote her story The Assassination of Margaret Thatcher, a deft, comic fantasy in which she entered the mind of a would-be IRA killer barging into a home in Windsor. For a week she was literally under siege from the UK media in Budleigh Salterton, enjoying the idiocy of politicians declaring she should be locked up, before they had even read the story.

She will be remembered for her enormous generosity to other budding writers, or indeed anyone who she had contact with in the arts and the media, her capacity to electrify a live audience, and the huge array of her journalism and criticism, producing some of the finest commentary on issues and books. Emails from Hilary were sprinkled with bon mots and jokes as she observed the world with relish and pounced on the lazy or absurd and nailed cruelty and prejudice. There was always a slight aura of otherworldliness about her, as she saw and felt things us ordinary mortals missed, but when she perceived the need to confront lies and injustice she would fearlessly go into battle. Brexit and her dismay at the last 10 years of UK politics provoked her to emigrate to Ireland: she and her husband Gerald had bought a house in County Cork just before she died.

She will be remembered for her enormous generosity to other budding writers, or indeed anyone she had contact with in the arts and the media

In 1990 she was elected as a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, in 2006 she was awarded a CBE and in 2014 she was appointed DBE. Hilary was patron of Scene & Heard, a theatrical mentoring project, governor of the RSC and president of the Budleigh Festival. She had a passion for cricket: she and Gerald often attended Lord’s for Sunday matches in the early days, and she was for some years the president of the Authors Cricket Team. She was an honorary fellow of the British Psychoanalytical Society, an honour obtained through Mike Brearley—another cricket connection. Her favourite food was meat and potato pie, made by herself; her favourite music was Bruce Springsteen and Tom Petty; and Holbein’s art, Shakespeare and Donne were always close to hand. She loved the TV series of “Game of Thrones”.

Art brings back the dead, but it also makes perpetual mourners of us all. This is from an essay she wrote about the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, summing up the connection between celebration and loss, life and memory. It seems apt to end with it.