You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

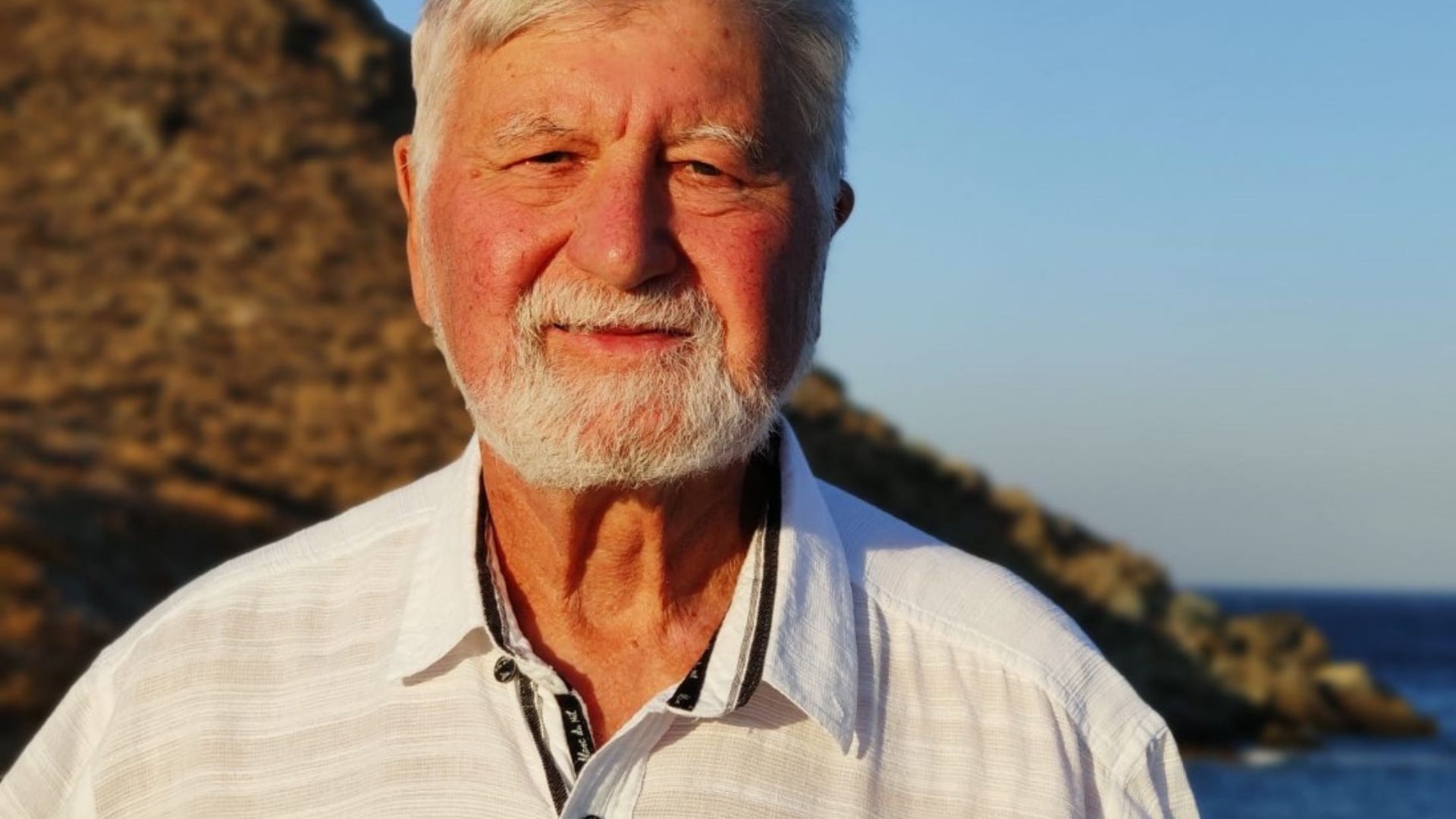

Obituary: Michael O’Brien

Michael O’Brien 4th July 1941–31st July 2022

When I first met Michael O’Brien, in 2001, he had a reputation as a maverick publisher with an uncanny knack for discovering authors and illustrators. As a wide-eyed newcomer, working closely with him was quite the learning curve. Michael had built The O’Brien Press from the ground up. His unorthodox upbringing instilled in him an appreciation for the arts and a drive to follow his instincts. His mother was of Crimean Jewish descent and his father was an Irish communist, one of 150 Irish to sign up with the International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War. As a young man, Michael joined his father Tom’s printing company. They co-founded The O’Brien Press in 1974, and when Tom died later that year, Michael committed full-time to publishing—a brave move, with only a few books under his belt and three children under the age of five. Over the next 48 years, The O’Brien Press was to publish more than 2,000 books by some of Ireland’s finest authors and illustrators.

Publishing in 1970s Ireland was a challenging business. In the mid-1970s, Michael travelled to his first Frankfurt Book Fair, hefty suitcase (sans wheels) in tow. After a week of flat rejection, he met with Don Sutherland of McGill-Queen’s University Press. Sutherland promptly bought North American rights to two titles, and so began The O’Brien Press’ rights operation, which has led to more than 750 foreign editions in 40 languages.

Michael thrived on risk. A true optimist, he followed his intuition; innovative and eclectic, he explored genres like true crime, graphic novels and humour. He was first to publish Brendan O’Carroll’s comic novel The Mammy, which was eventually turned into the hit TV series “Mrs Brown’s Boys”. As publisher, Michael pursued a social justice agenda. In 1993, he published When Love Comes to Town by Tom Lennon, an LGBTQ+ coming-of-age story set in contemporary Dublin, the first of its kind (and written under a pseudonym). It’s fitting that this year, in a much-changed Ireland, The O’Brien Press published its first LGBTQ+ picture book, Our Big Day by Bob Johnston, illustrated by Michael Emberley. In 1994, Michael published Patrick Touher’s Fear of the Collar, an explosive account of the abuse of children in Artane Industrial School, run by the Christian Brothers. Before publication, a detective requested a copy to help with investigations against some of the Brothers, an indication of the revelations to come.

The O’Brien Press published its first children’s book in 1977, when Irish children’s reading material was almost exclusively from Britain and the US. In the 1980s, Michael and long-time editorial director Ide ní Laoghaire set their sights on becoming Ireland’s foremost children’s publisher. Marita Conlon-McKenna’s Under the Hawthorn Tree (1990), a novel set during the Great Famine, was at the forefront of a new native literature for Irish children. Ireland’s bestselling kids’ book of the following decade, it won the International Reading Association Award and was translated widely. Now books for young people make up half our list, including the first works from Siobhán Parkinson and Eoin Colfer, and authors like Judi Curtin, Sarah Webb and Celine Kiernan. In 2006, Michael received the Award of the Decade from Children’s Books Ireland.

Michael was an ideas man and saw a potential book in everyone. At publishing meetings, it wasn’t unusual for him to produce a business card from someone he sat next to on the bus. Conversations with him were wide-ranging, unpredictable and almost always entertaining. He would sign up one book with an author, then immediately ask for another. After discussing, say, an historical non-fiction title, he would ask, “Have you ever considered writing for children?” He was incorrigible. He could throw ideas out at dizzying speed, leaving authors trying to catch up.

With that creativity came great passion. It’s safe to say that if you never had a lively disagreement with Michael, you didn’t know him very well. Michael always assured me that spirited discussion was the inevitable result of the creative process. Disagreement rarely bothered him, and he had that gift of being able to leave it behind and move on to whatever was next. As many will attest, he enjoyed the cut and thrust of negotiating book deals and always respected those who sought fairness for all.

Family was hugely important to Michael, and it meant a great deal to him that his sons Ivan and Eoin will carry on the family business. His family will, of course, miss him most of all. But for all of us at The O’Brien Press, his loss is palpable. We miss him when we see each new autumn title arrive, or when looking for an unvarnished reaction to a random idea, or when a meeting goes eerily smoothly. There is an Irish phrase that sums Michael up perfectly,

Ní bheidh a leitheid arís ann. We shall not see his like again.