You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

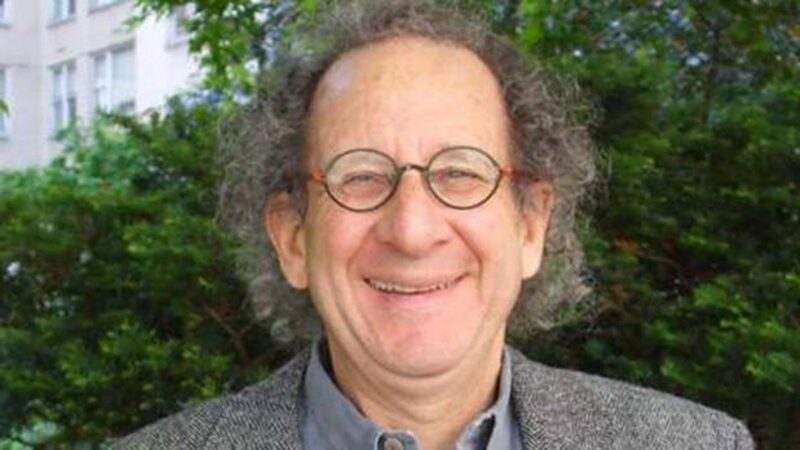

Obituary: Rebecca Swift

Rumbustious is the word Rebecca Swift (10th January 1964-18th April 2017) used to describe her adolescence. She carried this quality - and its synonyms: exuberant, boisterous, noisy, uproarious - to the end of her too-short life, alongside a very different set of characteristics: thoughtfulness, empathy, sensitivity and sometimes fragility.

She was the daughter of Margaret Drabble and the actor Clive Swift, and her love for literature, music and theatricality was part of her inheritance from her parents. In her twenties she started to work at Virago, where she found herself particularly drawn to the slush pile. Considering all the work that had gone into producing those manuscripts, and the perfunctory form-letters of rejection that were the almost invariable response, she recognised the “potential toxicity” of the situation, which she thought about in terms of lines from William Empson’ s “Missing Dates”: “Slowly the poison the whole blood stream fills/It is not the effort nor the failure tires/The waste remains, the waste remains and kills.” She was convinced that writers craved professional assessment and also aware of the many underutilised editors who had gone freelance as a result of changes in publishing in the 1980s. Bringing the two together seems obvious now, but was at the time visionary.

In 1996, after Virago was sold to Little, Brown and Becky was let go with (in her words) “a copper handshake”, she and Hannah Griffiths [former Faber publisher] set up The Literary Consultancy (TLC) to provide professional editorial services to writers working at all levels - the first company of its kind. It was very much in keeping with Becky’ s nature that she didn’ t conceive of TLC as a business that might show a profit by providing writers with advice on getting published, but rather as a “truth-telling” editorial service which would help people understand why their work wasn’ t publishable.

As TLC flourished she was, of course, delighted by the number of its writers who did go on to be published, but she took great satisfaction from the Arts Council grant that enabled TLC to provide Free Reads to low-income writers. She wanted the company to reach as many people as possible. Another source of pride was the establishment last year of TLC Middle East.

Her interest in people’ s varied reasons for writing led her to an MA at the Tavistock Centre in 1999, for which she wrote the dissertation “Are you reading me? A psychodynamic exploration of people who write and readers in publishing and related industries.” Through her research she worked out that at most 1% of people writing fiction would be taken on by publishing houses. This reinforced her certainty that it would be unethical to pretend there’ s a market for everyone who writes, and also made her interested in the different avenues of self-publishing that appeared with the advent of the digital age. In 2012, at the Free Word Centre, of which she was a founding member, she set up the UK’ s first digital conference aimed at writers.

In November 2016, shortly after she had received the diagnosis of cancer, she was at her passionate, entertaining, analytical best at TLC’ s day-long 20th anniversary celebrations at the Free Word Centre. The day ended with a wonderful party, at which Becky took up a guitar and sang “Suzanne” in tribute to Leonard Cohen, who had died that day. She also paid tribute to her trusted co-workers, Aki Schilz, who is now running the company, and Joe Sedgwick.

In addition to being the co-founder and director of TLC, Becky was the editor of two books for Chatto, a widely anthologised poet, the librettist for the opera “Spirit Child”, and the author of the biography Emily Dickinson: Poetic Lives. She was also for several years a trustee of The Maya Centre - its work providing counselling for vulnerable women she felt particularly close to, given her own periods of clinical depression - and of Writers’ Centre Norwich.

When the severity of her illness became clear, Becky responded by seeking comfort in music, and the many people who loved her - particularly her partner, Helen Cosis Brown, and her mother, who were always by her side. Her sense of humour stayed with her to the end, as did the great generosity of her spirit and her reservoirs of emotional literacy.

She is survived by Helen and Helen’ s two sons and grandson; her parents and her step-father, Michael Holroyd; and her brothers, Adam and Joe, and their children.